PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians and Their Government

Table of Contents

California voters have now received their mail ballots, and the November 8 general election has entered its final stage. Amid rising prices and economic uncertainty—as well as deep partisan divisions over social and political issues—Californians are processing a great deal of information to help them choose state constitutional officers and state legislators and to make policy decisions about state propositions. The 2022 midterm election also features a closely divided Congress, with the likelihood that a few races in California may determine which party controls the US House.

These are among the key findings of a statewide survey on state and national issues conducted from October 14 to 23 by the Public Policy Institute of California:

- Many Californians have negative perceptions of their personal finances and the US economy. Seventy-six percent rate the nation’s economy as “not so good” or “poor.” Thirty-nine percent say their finances are “worse off” today than a year ago. Forty-seven percent say that things in California are going in the right direction, while 33 percent think things in the US are going in the right direction; partisans differ in their overall outlook.→

- Among likely voters, 55 percent would vote for Gavin Newsom and 36 percent would vote for Brian Dahle if the governor’s election were today. Partisans are deeply divided in their choices. Sixty percent are very or fairly closely following news about the governor’s race. Sixty-two percent are satisfied with the candidate choices in the governor’s election.→

- When likely voters are read the ballot title and labels, 34 percent would vote yes on Proposition 26 (sports betting at tribal casinos), 26 percent would vote yes on Proposition 27 (online sports gambling),and 41 percent would vote yes on Proposition 30 (reducing greenhouse gases). Most likely voters say they are not personally interested in sports betting, and 48 percent think it would be a “bad thing” if it became legal in the state. Fewer than half of likely voters say the vote outcome of Propositions 26, 27, or 30 is very important to them.→

- Fifty-six percent of likely voters would support the Democratic candidate in their US House race if the election were today. Sixty-one percent say the issue of abortion rights is very important in their vote for Congress this year; Democrats are far more likely than Republicans or independents to hold this view. About half are “extremely” or “very” enthusiastic about voting for Congress this year; 54 percent of Republicans and Democrats, and 41 percent of independents, are highly enthusiastic this year.→

- Forty-five percent of Californians and 40 percent of likely voters are satisfied with the way that democracy is working in the United States. Republicans are far less likely than Democrats and independents to hold this positive view. There is rare partisan consensus on one topic: majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and independents are pessimistic that Americans with different political views can still come together and work out their differences.→

- Majorities of California adults and likely voters approve of Governor Gavin Newsom and President Joe Biden. About four in ten or more California adults and likely voters approve of US Senator Dianne Feinstein and US Senator Alex Padilla. These approval ratings vary across partisan groups. Approval of the state legislature is higher than approval of the US Congress.→

Overall Mood

With less than two weeks to go until what is set to be a highly consequential midterm election, California adults are divided on whether the state is generally headed in the right direction (47%) or wrong direction (48%); a majority of likely voters (54%) think the state is headed in the wrong direction (43% right direction). Similar shares held this view last month (wrong direction: 44% adults, 49% likely voters; right direction: 50% adults, 48% likely voters). Today, there is a wide partisan divide: seven in ten Democrats are optimistic about the direction of the state, while 91 percent of Republicans and 59 percent of independents are pessimistic. Majorities of residents in the Central Valley and Orange/San Diego say the state is going in the wrong direction, while a majority in the San Francisco Bay Area say right direction; adults elsewhere are divided. Across demographic groups, Californians ages 18 to 34 (60%), Asian Americans (52%), college graduates (52%), renters (52%), and women (52%) are the only groups in which a majority are optimistic about California’s direction.

Californians are much more pessimistic about the direction of the country than they are about the direction of the state. Solid majorities of adults (62%) and likely voters (71%) say the United States is going in the wrong direction, and majorities have held this view since September 2021. One in three or fewer adults (33%) and likely voters (25%) think the country is going in the right direction. Majorities across all demographic groups and partisan groups, as well as across regions, are pessimistic about the direction of the United States.

The state of the economy and inflation are likely to play a critical role in the upcoming election, and about four in ten adults (39%) and likely voters (43%) say they and their family are worse off financially than they were a year ago. Similar shares say they are financially in about the same spot (43% adults, 44% likely voters). The share who feel they are worse off has risen slightly among likely voters since May, but is similar among adults (37% adults, 36% likely voters). Fewer than two in ten Californians say they are better off than they were one year ago (17% adults, 13% likely voters). A wide partisan divide exists: most Democrats and independents say their financial situation is about the same as a year ago, while solid majorities of Republicans say they are worse off. Regionally, about half in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles say they are about the same, while half in the Central Valley say they are worse off; residents elsewhere are divided between being worse off and the same. Across demographic groups, pluralities say they are either financially about the same as last year or worse off, with the exception of African Americans (51% about the same, 33% worse off, 16% better off) and Asian Americans (51% about the same, 27% worse off, 20% better off). The shares saying they are worse off decline as educational attainment increases.

With persistent inflation and concerns about a possible recession in the future, an overwhelming majority of Californians believe the US economy is in not so good (43% adults, 40% likely voters) or poor (33% adults, 36% likely voters) shape. About a quarter of adults (3% excellent, 20% good) and likely voters (2% excellent, 23% good) feel positively about the national economy. Strong majorities across partisan groups feel negatively, but Republicans and independents are much more likely than Democrats to say the economy is in poor shape. Solid majorities across the state’s major regions as well as all demographic groups say the economy is in not so good or poor shape. In a recent ABC News/Washington Post poll, 24 percent (3% excellent, 21% good) of adults nationwide felt positively about the US economy, while 74 percent (36% not so good, 38% poor) expressed negative views.

Gubernatorial Election

Six in ten likely voters say they are following news about the 2022 governor’s race very (25%) or fairly (35%) closely—a share that has risen from half just a month ago (17% very, 33% fairly). This finding is somewhat similar to October 2018, when 68 percent said this (28% very, 40% closely) a month before the previous gubernatorial election. Today, majorities across partisan, demographic, and regional groups say they are following news about the gubernatorial election either very or fairly closely. The shares saying they are following the news very closely is highest among residents in Republican districts (39%), Republicans (30%), whites (29%), and adults with incomes of $40,000 to $79,999 (29%). Older likely voters (27%) are slightly more likely than younger likely voters (21%) to say they are following the news closely.

Democratic incumbent Gavin Newsom is ahead of Republican Brian Dahle (55% to 36%) among likely voters, while few say they would not vote, would vote for neither, or don’t know who they would vote for in the governor’s race. The share supporting the reelection of the governor was similar a month ago (58% Newsom, 31% Dahle). Today, Newsom enjoys the support of most Democrats (91%), while most Republicans (86%) support Dahle; Newsom has an edge over Dahle among independent likely voters (47% Newsom, 37% Dahle). Across the state’s regions, two in three in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles support Newsom, as do nearly half in the Inland Empire and Orange/San Diego; likely voters in the Central Valley are split. Newsom leads in all demographic groups, with the exception of men (45% Newsom, 44% Dahle) and those with a high school diploma only (46% Newsom, 49% Dahle). The share supporting Newsom grows as educational attainment increases (46% high school only, 56% some college, 60% college graduates), while it decreases with rising income (64% less than $40,000, 56% $40,000 to $79,999, 52% $80,000 or more).

A solid majority of likely voters (62%) are satisfied with their choices of candidates in the November 8 election, while about three in ten (32%) are not satisfied. Shares expressing satisfaction have increased somewhat from a month ago (53%) and were similar prior to the 2018 gubernatorial election (60% October 2018). Today, a solid majority of Democrats (79%) and independents (61%) say they are satisfied, compared to fewer than half of Republicans (44%). Majorities across demographic groups say they are satisfied, and notably, women (68%) are more likely than men (56%) to say this. Majorities across the state’s regions say they are satisfied with their choices of candidates in the upcoming gubernatorial election.

State Propositions 26, 27, and 30

In the upcoming November 8 election, there will be seven state propositions for voters. Due to time constraints, our survey only asked about three ballot measures: Propositions 26, 27, and 30. For each, we read the proposition number, ballot, and ballot label. Two of the state ballot measures were also included in the September survey (Propositions 27 and 30), while Proposition 26 was not.

If the election were held today, 34 percent of likely voters would vote “yes,” 57 percent would vote “no,” and 9 percent are unsure of how they would vote on Proposition 26—Allows In-Person Roulette, Dice, Game, Sports Wagering on Tribal Lands. This measure would allow in-person sports betting at racetracks and tribal casinos, requiring that racetracks and casinos offering sports betting make certain payments to the state to support state regulatory costs. It also allows roulette and dice games at tribal casinos and adds a new way to enforce certain state gambling laws. There is partisan agreement on Prop 26: fewer than four in ten Democrats, Republicans, and independents would vote “yes.” Moreover, less than a majority across all regions and demographic groups—with the exception of likely voters ages 18 to 44 (51% yes, 44% no)—would vote “yes.”

If the election were held today, 26 percent of likely voters would vote “yes,” 67 percent would vote “no,” and 8 percent are unsure of how they would vote on Proposition 27—Allows Online and Mobile Sports Wagering Outside Tribal Lands. This citizens’ initiative would allow Indian tribes and affiliated businesses to operate online and mobile sports wagering outside tribal lands. Strong majorities across partisan groups would vote “no” on Prop 27. The share voting “yes” has decreased since a month ago (34% September). Today, fewer than three in ten across partisan groups would vote “yes” on Prop 27. Moreover, fewer than four in ten across regions, gender, racial/ethnic, education, and income groups would vote “yes.” Likely voters ages 18 to 44 (41%) are far more likely than older likely voters ages 45 and above (19%) to say they would vote “yes.”

If the election were held today, 41 percent of likely voters would vote “yes,” 52 percent would vote “no,” and 7 percent are unsure of how they would vote on Proposition 30—Provides Funding for Programs to Reduce Air Pollution and Prevent Wildfires by Increasing Tax on Personal Income over $2 Million. This citizens’ initiative would increase taxes on Californians earning more than $2 million annually and allocate that tax revenue to zero-emission vehicle purchase incentives, vehicle charging stations, and wildfire prevention. The share saying “yes” on Prop 30 has decreased from 55 percent in our September survey (note: since September, Governor Newsom has been featured in “no on Prop 30” commercials). Today, unlike Prop 26 and Prop 27, partisan opinions are divided on Prop 30: 61 percent of Democrats would vote “yes,” compared to far fewer Republicans (15%) and independents (38%). Across regions, and among men and women, support falls short of a majority (36% men, 45% women). Fewer than half across racial/ethnic groups say they would vote “yes” (39% whites, 42% Latinos, 46% other racial/ethnic groups). Just over half of likely voters with incomes under $40,000 (52%) would vote “yes,” compared to fewer in higher-income groups (42% $40,000 to $79,999, 36% $80,000 or more). Nearly half of likely voters ages 18 to 44 (49%) would vote “yes,” compared to 37 percent of older likely voters.

Fewer than half of likely voters say the outcome of each of these state propositions is very important to them. Today, 21 percent of likely voters say the outcome of Prop 26 is very important, 31 percent say the outcome of Prop 27 is very important, and 42 percent say the outcome of Prop 30 is very important. The shares saying the outcomes are very important to them have remained similar to a month ago for Prop 27 (29%) and Prop 30 (42%). Today, when it comes to the importance of the outcome of Prop 26, one in four or fewer across partisan groups say it is very important to them. About one in three across partisan groups say the outcome of Prop 27 is very important to them. Fewer than half across partisan groups say the outcome of Prop 30 is very important to them.

Congressional Elections

When asked how they would vote if the 2022 election for the US House of Representatives were held today, 56 percent of likely voters say they would vote for or lean toward the Democratic candidate, while 39 percent would vote for or lean toward the Republican candidate. In September, a similar share of likely voters preferred the Democratic candidate (60% Democrat/lean Democrat, 34% Republican/lean Republican). Today, overwhelming majorities of partisans support their party’s candidate, while independents are divided (50% Democrat/lean Democrat, 44% Republican/lean Republican). Democratic candidates are preferred by a 26-point margin in Democratic-held districts, while Republican candidates are preferred by a 23-point margin in Republican-held districts. In the ten competitive California districts as defined by the Cook Political Report, the Democratic candidate is preferred by a 22-point margin (54% to 32%).

Abortion is another prominent issue in this election. When asked about the importance of abortion rights, 61 percent of likely voters say the issue is very important in determining their vote for Congress and another 20 percent say it is somewhat important; just 17 percent say it is not too or not at all important. Among partisans, an overwhelming majority of Democrats (78%) and 55 percent of independents say it is very important, compared to 43 percent of Republicans. Majorities across regions and all demographic groups—with the exception of men (49% very important)—say abortion rights are very important when making their choice among candidates for Congress.

With the controlling party in Congress hanging in the balance, 51 percent of likely voters say they are extremely or very enthusiastic about voting for Congress this year; another 29 percent are somewhat enthusiastic while 19 percent are either not too or not at all enthusiastic. In October 2018 before the last midterm election, a similar 53 percent of likely voters were extremely or very enthusiastic about voting for Congress (25% extremely, 28% very, 28% somewhat, 10% not too, 8% not at all). Today, Democrats and Republicans have about equal levels of enthusiasm, while independents are much less likely to be extremely or very enthusiastic. Half or more across regions are at least very enthusiastic, with the exceptions of likely voters in Los Angeles (44%) and the San Francisco Bay Area (43%). At least half across demographic groups are highly enthusiastic, with the exceptions of likely voters earning $40,000 to $79,999 annually (48%), women (47%), Latinos (43%), those with a high school diploma or less (42%), renters (42%), and 18- to 44-year-olds (37%).

Democracy and the Political Divide

As Californians prepare to vote in the upcoming midterm election, fewer than half of adults and likely voters are satisfied with the way democracy is working in the United States—and few are very satisfied. Satisfaction was higher in our February survey when 53 percent of adults and 48 percent of likely voters were satisfied with democracy in America. Today, half of Democrats and about four in ten independents are satisfied, compared to about one in five Republicans. Notably, four in ten Republicans are not at all satisfied. Across regions, half of residents in the San Francisco Bay Area (52%) and the Inland Empire (50%) are satisfied, compared to fewer elsewhere. Across demographic groups, fewer than half are satisfied, with the exception of Latinos (56%), those with a high school degree or less (55%), and those making less than $40,000 (53%).

In addition to the lack of satisfaction with the way democracy is working, Californians are divided about whether Americans of different political positions can still come together and work out their differences. Forty-nine percent are optimistic, while 46 percent are pessimistic. Optimism has been similar in more recent years, but has decreased 7 points since we first asked this question in September 2017 (56%). In September 2020, just before the 2020 general election, Californians were also divided (47% optimistic, 49% pessimistic).

Today, in a rare moment of bipartisan agreement, about four in ten Democrats, Republicans, and independents are optimistic that Americans of different political views will be able to come together. Across regions, about half in Orange/San Diego, the Inland Empire, and the San Francisco Bay Area are optimistic. Across demographic groups, only the following groups have a majority or more who are optimistic: African Americans and Latinos (61% each), those with a high school diploma or less (63%), and those with household incomes under $40,000 (61%). Notably, in 2017, half or more across parties, regions, and demographic groups were optimistic.

Approval Ratings

With about two weeks to go before Governor Newsom’s bid for reelection, a majority of Californians (54%) and likely voters (52%) approve of the way he is handling his job, while fewer disapprove (33% adults, 45% likely voters). Approval was nearly identical in September (52% adults, 55% likely voters) and has been 50 percent or more since January 2020. Today, about eight in ten Democrats—compared to about half of independents and about one in ten Republicans—approve of Governor Newsom. Half or more across regions approve of Newsom, except in the Central Valley (42%). Across demographic groups, about half or more approve of how Governor Newsom is handling his job.

With all 80 state assembly positions and half of state senate seats up for election, fewer than half of adults (49%) and likely voters (43%) approve of the way that the California Legislature is handling its job. Views are deeply divided along partisan lines; approval is highest in the San Francisco Bay Area and lowest in Orange/San Diego. About half across racial/ethnic groups approve, and approval is much higher among younger Californians.

Majorities of California adults (53%) and likely voters (52%) approve of the way President Biden is handling his job, while fewer disapprove (43% adults, 47% likely voters). Approval is similar to September (53% adults and likely voters), and Biden’s approval rating among adults has been at 50 percent or higher since we first asked this question in January 2021. Today, about eight in ten Democrats approve of Biden’s job performance, compared to about four in ten independents and one in ten Republicans. Approval is higher in the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles than in the Inland Empire, Orange/San Diego, and the Central Valley. About half or more across demographic groups approve of President Biden, with the exception of those with some college education (44%).

Approval of Congress remains low, with fewer than four in ten adults (37%) and likely voters (29%) approving. Approval of Congress among adults has been below 40 percent for all of 2022 after seeing a brief run above 40 percent for all of 2021. Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to approve of Congress. Fewer than half across regions and demographic groups approve of Congress.

US Senator Alex Padilla is on the California ballot twice this November—once for the remainder of Vice President Harris’s term and once for reelection. Senator Padilla has the approval of 46 percent of adults and 48 percent of likely voters (adults: 26% disapprove, 29% don’t know; likely voters: 31% disapprove, 22% don’t know). Approval in March was at 44 percent for adults and 39 percent for likely voters. Today, Padilla’s approval rating is much higher among Democrats than independents and Republicans. Across regions, about half in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and the Inland Empire approve of the US senator, compared to four in ten in Orange/San Diego and one in three in the Central Valley. Across demographic groups, about half or more approve among women, younger adults, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos. Views are similar across education and income groups, with just fewer than half approving.

US Senator Dianne Feinstein—who is not on the California ballot this November—has the approval of 41 percent of adults and likely voters (adults: 42% disapprove, 17% don’t know; likely voters: 52% disapprove, 7% don’t know). Approval in March was at 41 percent for adults and 36 percent for likely voters. Today, Feinstein’s approval rating is far higher among Democrats and independents than Republicans. Across regions, approval reaches a majority only in the San Francisco Bay Area. Across demographic groups, approval reaches a majority only among African Americans

Regional Map

This map highlights the five geographic regions for which we present results; these regions account for approximately 90 percent of the state population. Residents of other geographic areas (in gray) are included in the results reported for all adults, registered voters, and likely voters, but sample sizes for these less-populous areas are not large enough to report separately.

Methodology

The PPIC Statewide Survey is directed by Mark Baldassare, president and CEO and survey director at the Public Policy Institute of California. Coauthors of this report include survey analyst Deja Thomas, who was the project manager for this survey; associate survey director and research fellow Dean Bonner; and survey analyst Rachel Lawler. The Californians and Their Government survey is supported with funding from the Arjay and Frances F. Miller Foundation and the James Irvine Foundation. The PPIC Statewide Survey invites input, comments, and suggestions from policy and public opinion experts and from its own advisory committee, but survey methods, questions, and content are determined solely by PPIC’s survey team.

Findings in this report are based on a survey of 1,715 California adult residents, including 1,263 interviewed on cell phones and 452 interviewed on landline telephones. The sample included 569 respondents reached by calling back respondents who had previously completed an interview in PPIC Statewide Surveys in the last six months. Interviews took an average of 19 minutes to complete. Interviewing took place on weekend days and weekday nights from October 14–23, 2022.

Cell phone interviews were conducted using a computer-generated random sample of cell phone numbers. Additionally, we utilized a registration-based sample (RBS) of cell phone numbers for adults who are registered to vote in California. All cell phone numbers with California area codes were eligible for selection. After a cell phone user was reached, the interviewer verified that this person was age 18 or older, a resident of California, and in a safe place to continue the survey (e.g., not driving). Cell phone respondents were offered a small reimbursement to help defray the cost of the call. Cell phone interviews were conducted with adults who have cell phone service only and with those who have both cell phone and landline service in the household.

Landline interviews were conducted using a computer-generated random sample of telephone numbers that ensured that both listed and unlisted numbers were called. Additionally, we utilized a registration-based sample (RBS) of landline phone numbers for adults who are registered to vote in California. All landline telephone exchanges in California were eligible for selection. After a household was reached, an adult respondent (age 18 or older) was randomly chosen for interviewing using the “last birthday method” to avoid biases in age and gender.

For both cell phones and landlines, telephone numbers were called as many as eight times. When no contact with an individual was made, calls to a number were limited to six. Also, to increase our ability to interview Asian American adults, we made up to three additional calls to phone numbers estimated by Survey Sampling International as likely to be associated with Asian American individuals.

Live landline and cell phone interviews were conducted by Abt Associates in English and Spanish, according to respondents’ preferences. Accent on Languages, Inc., translated new survey questions into Spanish, with assistance from Renatta DeFever.

Abt Associates uses the US Census Bureau’s 2016–2020 American Community Survey’s (ACS) Public Use Microdata Series for California (with regional coding information from the University of Minnesota’s Integrated Public Use Microdata Series for California) to compare certain demographic characteristics of the survey sample—region, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education—with the characteristics of California’s adult population. The survey sample was closely comparable to the ACS figures. To estimate landline and cell phone service in California, Abt Associates used 2019 state-level estimates released by the National Center for Health Statistics—which used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and the ACS. The estimates for California were then compared against landline and cell phone service reported in this survey. We also used voter registration data from the California Secretary of State to compare the party registration of registered voters in our sample to party registration statewide. The landline and cell phone samples were then integrated using a frame integration weight, while sample balancing adjusted for differences across region, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, telephone service, and party registration groups.

The sampling error, taking design effects from weighting into consideration, is ±3.9 percent at the 95-percent confidence level for the total unweighted sample of 1,715 adults. This means that 95 times out of 100, the results will be within 3.9 percentage points of what they would be if all adults in California were interviewed. The sampling error for unweighted subgroups is larger: for the 1,439 registered voters, the sampling error is ±4.5 percent; for the 1,111 likely voters, it is ±5.1 percent. For the sampling errors of additional subgroups, please see the table at the end of this section. Sampling error is only one type of error to which surveys are subject. Results may also be affected by factors such as question wording, question order, and survey timing.

We present results for five geographic regions, accounting for approximately 90 percent of the state population. “Central Valley” includes Butte, Colusa, El Dorado, Fresno, Glenn, Kern, Kings, Madera, Merced, Placer, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Shasta, Stanislaus, Sutter, Tehama, Tulare, Yolo, and Yuba Counties. “San Francisco Bay Area” includes Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano, and Sonoma Counties. “Los Angeles” refers to Los Angeles County, “Inland Empire” refers to Riverside and San Bernardino Counties, and “Orange/San Diego” refers to Orange and San Diego Counties. Residents of other geographic areas are included in the results reported for all adults, registered voters, and likely voters, but sample sizes for these less-populous areas are not large enough to report separately. We also present results for congressional districts currently held by Democrats or Republicans, based on residential zip code and party of the local US House member. We analyze the results of those who live in competitive house districts as determined by the Cook Political Report’s 2022 House Race Ratings updated September 1, 2022. These districts are 3, 9, 13, 22, 27, 40, 41, 45, 47, and 49; a map of California’s congressional districts can be found here.

We present results for non-Hispanic whites, who account for 41 percent of the state’s adult population, and also for Latinos, who account for about a third of the state’s adult population and constitute one of the fastest-growing voter groups. We also present results for non-Hispanic Asian Americans, who make up about 16 percent of the state’s adult population, and non-Hispanic African Americans, who comprise about 6 percent. Results for other racial/ethnic groups—such as Native Americans—are included in the results reported for all adults, registered voters, and likely voters, but sample sizes are not large enough for separate analysis. Results for African American and Asian American likely voters are combined with those of other racial/ethnic groups because sample sizes for African American and Asian American likely voters are too small for separate analysis. We compare the opinions of those who report they are registered Democrats, registered Republicans, and no party preference or decline-to-state or independent voters; the results for those who say they are registered to vote in other parties are not large enough for separate analysis. We also analyze the responses of likely voters—so designated per their responses to survey questions about voter registration, previous election participation, intentions to vote this year, attention to election news, and current interest in politics.

The percentages presented in the report tables and in the questionnaire may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Numerous questions were adapted from national surveys by ABC News/Washington Post, CBS News, NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist, and the Pew Research Center. Additional details about our methodology can be found at www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/SurveyMethodology.pdf and are available upon request through surveys@ppic.org.

Questions and Responses

October 14–23, 2022

1,715 California adult residents; 1,111 California likely voters

English, Spanish

Margin of error ±3.9% at 95% confidence level for the total sample, ±5.1% for likely voters. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

1. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way that Gavin Newsom is handling his job as governor of California?

54% approve

33% disapprove

14% don’t know

2. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way that the California Legislature is handling its job?

49% approve

37% disapprove

14% don’t know

3. Do you think things in California are generally going in the right direction or the wrong direction?

47% right direction

48% wrong direction

5% don’t know

4. Thinking about your own personal finances—would you say that you and your family are financially better off, worse off, or just about the same as a year ago?

17% better off

39% worse off

43% same

1% don’t know

5. Next, some people are registered to vote and others are not. Are you absolutely certain that you are registered to vote in California?

74% yes [ask q5a]

26% no [skip to q6b]

5a. Are you registered as a Democrat, a Republican, another party, or are you registered as a decline-to-state or independent voter?

47% Democrat [ask q6]

24% Republican [ask q6a]

6% another party (specify) [skip to q7]

23% decline-to-state/independent [skip to 6b]

[likely voters only]

47% Democrat [ask q6]

27% Republican [ask q6a]

5% another party (specify) [skip to q7]

20% decline-to-state/independent [skip to 6b]

6. Would you call yourself a strong Democrat or not a very strong Democrat?

61% strong

37% not very strong

2% don’t know

[skip to q7]

6a. Would you call yourself a strong Republican or not a very strong Republican?

60% strong

38% not very strong

2% don’t know

[skip to q7]

6b. Do you think of yourself as closer to the Republican Party or Democratic Party?

23% Republican Party

44% Democratic Party

24% neither (volunteered)

9% don’t know

7. [likely voters only] If the November 8th election for governor were being held today, would you vote for [rotate] [1] Brian Dahle, a Republican, [or] [2] Gavin Newsom, a Democrat?

36% Brian Dahle, a Republican

55% Gavin Newsom, a Democrat

4% neither/would not vote for governor (volunteered)

5% don’t know

8. [likely voters only] How closely are you following news about candidates for the 2022 governor’s election—very closely, fairly closely, not too closely, or not at all closely?

25% very closely

35% fairly closely

25% not too closely

15% not at all closely

– don’t know

9. [likely voters only] In general, would you say you are satisfied or not satisfied with your choices of candidates in the election for governor on November 8th?

62% satisfied

32% not satisfied

6% don’t know

Changing topics,

10. [likely voters only] If the 2022 election for US House of Representatives were being held today, would you vote for [rotate] [1] the Republican candidate [or] [2] the Democratic candidate in your district? (ask if ‘other’ or ‘don’t know’: “As of today, do you lean more toward [read in same order as above] [1] the Republican candidate [or] [2] the Democratic candidate?”)

39% Republican/lean Republican

56% Democrat/lean Democrat

5% don’t know

11. [likely voters only] How important is the issue of abortion rights in your vote for Congress this year—is it very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important?

61% very important

20% somewhat important

7% not too important

10% not at all important

– don’t know

12. [likely voters only] How enthusiastic would you say you are about voting for Congress this year—extremely enthusiastic, very enthusiastic, somewhat enthusiastic, not too enthusiastic, or not at all enthusiastic?

18% extremely enthusiastic

33% very enthusiastic

29% somewhat enthusiastic

14% not too enthusiastic

5% not at all enthusiastic

1% don’t know

Next, we have a few questions to ask you about some of the propositions on the November ballot.

13. [likely voters only] There are five citizens’ initiatives, one referendum, and one legislative constitutional amendment on the November 8 state ballot. Which one of the seven state propositions on the November 8 ballot are you most interested in?

20% Proposition 1 Constitutional Right to Reproductive Freedom, Abortion, Contraceptives

4% Proposition 26 Sports Betting at Tribal Casinos

10% Proposition 27 Allow Online Sports Betting

2% Proposition 28 Arts and Music Education Funding in Public Schools

7% Proposition 29 Impose New Rules on Dialysis Clinics

4% Proposition 30 Tax Millionaires for Electric Vehicle Programs, Wildfire Response and Prevention

3% Proposition 31 Uphold Flavored Tobacco Ban

11% none of them (volunteered)

4% all equally (volunteered)

1% other (specify) (volunteered)

33% don’t know

14. [likely voters only] Proposition 26 is called Allows In-Person Roulette, Dice Game, Sports Wagering on Tribal Lands. Initiative Constitutional Amendment and Statute. It allows in-person sports betting at racetracks and tribal casinos, and requires that racetracks and casinos that offer sports betting to make certain payments to the state—such as to support state regulatory costs. The fiscal impact is increased state revenues, possibly reaching tens of millions of dollars annually. Some of these revenues would support increased state regulatory and enforcement costs that could reach the low tens of millions of dollars annually. If the election were held today, would you vote yes or no on Proposition 26?

34% yes

57% no

9% don’t know

15. [likely voters only] How important to you is the outcome of the vote on Proposition 26—is it very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important?

21% very important

37% somewhat important

26% not too important

11% not at all important

5% don’t know

Next,

16. [likely voters only] Proposition 27 is called Allows Online and Mobile Sports Wagering Outside Tribal Lands. Initiative Constitutional Amendment. It allows Indian tribes and affiliated businesses to operate online and mobile sports wagering outside tribal lands. It directs revenues to regulatory costs, homelessness programs, and nonparticipating tribes. The fiscal impact is increased state revenues, possibly in the hundreds of millions of dollars but not likely to exceed $500 million annually. Some revenues would support state regulatory costs, possibly reaching the mid-tens of millions of dollars annually. If the election were held today, would you vote yes or no on Proposition 27?

26% yes

67% no

8% don’t know

17. [likely voters only] How important to you is the outcome of the vote on Proposition 27—is it very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important?

31% very important

34% somewhat important

22% not too important

9% not at all important

4% don’t know

18. [likely voters only] Would you say you are personally interested in betting on sports, or not?

9% yes, interested

90% no, not interested

– don’t know

19. [likely voters only] Thinking about the fact that betting money on sports is now legal in most of the country—if sports betting was made legal in California, do you think this would be a good thing or bad thing for the state?

30% good thing

48% bad thing

11% neither a good thing nor bad thing, doesn’t matter (volunteered)

11% don’t know

Next,

20. [likely voters only] Proposition 30 is called Provides Funding for Programs to Reduce Air Pollution and Prevent Wildfires by Increasing Tax on Personal Income over $2 Million. Initiative Statute. It allocates tax revenues to zero-emission vehicle purchase incentives, vehicle charging stations, and wildfire prevention. The fiscal impact is increased state tax revenue ranging from $3.5 billion to $5 billion annually, with the new funding used to support zero-emission vehicle programs and wildfire response and prevention activities. If the election were held today, would you vote yes or no on Proposition 30?

41% yes

52% no

7% don’t know

21. [likely voters only] How important to you is the outcome of the vote on Proposition 30—is it very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important?

42% very important

38% somewhat important

13% not too important

4% not at all important

3% don’t know

Next, we are interested in your opinions about the citizens’ initiatives and referenda that appear on the state ballot as propositions this fall. Do you agree or disagree with these statements?

[rotate questions 22 and 23]

22. [likely voters only] There are too many propositions on the state ballot—do you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree?

20% strongly agree

27% somewhat agree

27% somewhat disagree

22% strongly disagree

5% don’t know

23. [likely voters only] The propositions on the state ballot reflect the concerns of average California residents—do you strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree?

14% strongly agree

36% somewhat agree

25% somewhat disagree

21% strongly disagree

4% don’t know

Reforms have been suggested to address issues in California’s direct democracy process.

24. [likely voters only] Would you favor or oppose a new law that would increase the number of signatures required to qualify an initiative, referendum, or recall for the state ballot?

43% favor

46% oppose

10% don’t know

25. [likely voters only] Would you favor or oppose a new law that would allow electronic signature gathering over the internet to qualify an initiative, referendum, or recall for the state ballot?

31% favor

64% oppose

5% don’t know

Changing topics,

26. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way that Joe Biden is handling his job as president?

53% approve

43% disapprove

4% don’t know

[rotate questions 27 and 28]

27. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way Alex Padilla is handling his job as US Senator?

46% approve

26% disapprove

29% don’t know

28. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way Dianne Feinstein is handling her job as US Senator?

41% approve

42% disapprove

17% don’t know

29. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the way the US Congress is handling its job?

37% approve

57% disapprove

7% don’t know

Next,

30. Do you think things in the United States are generally going in the right direction or the wrong direction?

33% right direction

62% wrong direction

5% don’t know

31. Would you describe the state of the nation’s economy these days as excellent, good, not so good, or poor?

3% excellent

20% good

43% not so good

33% poor

1% don’t know

Next,

32. How satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in the United States? Are you very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not too satisfied, or not at all satisfied?

7% very satisfied

38% somewhat satisfied

29% not too satisfied

23% not at all satisfied

2% don’t know

33. These days, do you feel [rotate] [1] (optimistic) [or] [2] (pessimistic) that Americans of different political views can still come together and work out their differences?

49% optimistic

46% pessimistic

4% don’t know

On another topic,

34. What is your opinion with regard to race relations in the United States today? Would you say things are [rotate 1 and 2] [1] (better), [2] (worse), or about the same than they were a year ago?

20% better

35% worse

44% about the same

2% don’t know

35. When it comes to racial discrimination, which do you think is the bigger problem for the country today—[rotate] [1] People seeing racial discrimination where it really does NOT exist [or] [2] People NOT seeing racial discrimination where it really DOES exist?

37% people seeing racial discrimination where it really does not exist

54% people not seeing racial discrimination where it really does exist

9% don’t know

Next,

36. Next, would you consider yourself to be politically: [read list, rotate order top to bottom]

17% very liberal

19% somewhat liberal

29% middle-of-the-road

20% somewhat conservative

12% very conservative

3% don’t know

37. Generally speaking, how much interest would you say you have in politics—a great deal, a fair amount, only a little, or none?

26% great deal

37% fair amount

28% only a little

8% none

-% don’t know

[d1–d15 demographic questions]

Authors

Mark Baldassare is president and CEO of the Public Policy Institute of California, where he holds the Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Public Policy. He is a leading expert on public opinion and survey methodology, and has directed the PPIC Statewide Survey since 1998. He is an authority on elections, voter behavior, and political and fiscal reform, and the author of ten books and numerous publications. Previously, he served as PPIC’s director of research and senior fellow. Before joining PPIC, he was a professor of urban and regional planning in the School of Social Ecology at the University of California, Irvine, where he held the Johnson Chair in Civic Governance. He has conducted surveys for the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the California Business Roundtable. He holds a PhD in sociology from the University of California, Berkeley.

Dean Bonner is associate survey director and research fellow at PPIC, where he coauthors the PPIC Statewide Survey—a large-scale public opinion project designed to develop an in-depth profile of the social, economic, and political attitudes at work in California elections and policymaking. He has expertise in public opinion and survey research, political attitudes and participation, and voting behavior. Before joining PPIC, he taught political science at Tulane University and was a research associate at the University of New Orleans Survey Research Center. He holds a PhD and MA in political science from the University of New Orleans.

Rachel Lawler is a survey analyst at the Public Policy Institute of California, where she works with the statewide survey team. Prior to joining PPIC, she was a client manager in Kantar Millward Brown’s Dublin, Ireland office. In that role, she led and contributed to a variety of quantitative and qualitative studies for both government and corporate clients. She holds an MA in American politics and foreign policy from the University College Dublin and a BA in political science from Chapman University.

Deja Thomas is a survey analyst at the Public Policy Institute of California, where she works with the statewide survey team. Prior to joining PPIC, she was a research assistant with the social and demographic trends team at the Pew Research Center. In that role, she contributed to a variety of national quantitative and qualitative survey studies. She holds a BA in psychology from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Acknowledgments

This survey was supported with funding from the Arjay and Frances F. Miller Foundation and the James Irvine Foundation.

PPIC Statewide Advisory Committee

Ruben Barrales

Senior Vice President, External Relations

Wells Fargo

Angela Glover Blackwell

Founder in Residence

PolicyLink

Mollyann Brodie

Executive Vice President and

Chief Operating Officer

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Bruce E. Cain

Director

Bill Lane Center for the American West

Stanford University

Jon Cohen

Chief Research Officer and Senior Vice President,

Strategic Partnerships and Business Development

Momentive-AI

Joshua J. Dyck

Co-Director

Center for Public Opinion

University of Massachusetts, Lowell

Lisa García Bedolla

Vice Provost for Graduate Studies and

Dean of the Graduate Division

University of California, Berkeley

Russell Hancock

President and CEO

Joint Venture Silicon Valley

Sherry Bebitch Jeffe

Professor

Sol Price School of Public Policy

University of Southern California

Robert Lapsley

President

California Business Roundtable

Carol S. Larson

President Emeritus

The David and Lucile Packard Foundation

Donna Lucas

Chief Executive Officer & Founder

Lucas Public Affairs

Sonja Petek

Fiscal and Policy Analyst

California Legislative Analyst’s Office

Lisa Pitney

Vice President of Government Relations

The Walt Disney Company

Robert K. Ross, MD

President and CEO

The California Endowment

Jui Shrestha

Survey Specialist Consultant

World Bank

Most Reverend Jaime Soto

Bishop of Sacramento

Roman Catholic Diocese of Sacramento

Helen Iris Torres

CEO

Hispanas Organized for Political Equality

David C. Wilson, PhD

Dean and Professor

Richard and Rhoda Goldman School

of Public Policy

University of California, Berkeley

PPIC Board of Directors

Chet Hewitt, Chair

President and CEO

Sierra Health Foundation

Mark Baldassare

President and CEO

Public Policy Institute of California

Ophelia Basgal

Affiliate

Terner Center for Housing Innovation

University of California, Berkeley

Louise Henry Bryson

Chair Emerita, Board of Trustees

J. Paul Getty Trust

Sandra Celedon

President and CEO

Fresno Building Healthy Communities

A. Marisa Chun

Judge, Superior Court of California, County of San Francisco

Phil Isenberg

Former Chair

Delta Stewardship Council

Mas Masumoto

Author and Farmer

Steven A. Merksamer

Of Counsel

Nielsen Merksamer Parrinello

Gross & Leoni LLP

Steven J. Olson

Partner

O’Melveny & Myers LLP

Leon E. Panetta

Chairman

The Panetta Institute for Public Policy

Gerald L. Parsky

Chairman

Aurora Capital Group

Kim Polese

Chairman and Co-founder

CrowdSmart

Cassandra Walker Pye

President

Lucas Public Affairs

Helen Iris Torres

CEO

Hispanas Organized for Political Equality

Gaddi H. Vasquez

Retired Senior Vice President, Government Affairs

Edison International

Southern California Edison

Copyright

© 2022 Public Policy Institute of California

The Public Policy Institute of California is dedicated to informing and improving public policy in California through independent, objective, nonpartisan research.

PPIC is a public charity. It does not take or support positions on any ballot measures or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office.

Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source.

Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or of the staff, officers, advisory councils, or board of directors of the Public Policy Institute of California.

The best times to visit South Africa, for beaches, wildlife and more

From dynamic Cape Town and the cosmopolitan vibes of Johannesburg to wildlife-filled expanses of wilderness such as the Kalahari and the Drakensberg mountains, South Africa has something for every kind of traveler. The best time to come will depend on where you want to go and what you want to do when you get here.

In general, the climate in South Africa is warmer in the north and cooler in the south. You’ll also find different weather on the coasts compared to the elevated plateau that makes up most of the country, where it tends to be drier. The Indian Ocean coast tends to feel more tropical, while the weather on the Atlantic coast is usually milder, though cold fogs and hot desert winds can still roll in.

Cape Town and the Western Cape are unique, weather-wise, having their rainy season in the winter (June to August). In the rest of the country, the rains arrive in the Southern Hemisphere summer (November through March), but the deluges rarely last for long (and there’s the chance of a photogenic thunderstorm).

For many visitors, the weather is less of a factor than South Africa’s vibrant festivals and the annual migrations and breeding seasons for the country’s diverse wildlife populations. Whatever draws you to South Africa, here’s a guide to the best times to come.

When to visit South Africa’s game reserves

Rain is most likely to interfere with your travels if you’re on safari. Northern game reserves such as Kruger National Park are driest from May to September, during the South African winter. While you might not have the lush backgrounds to your photos that you would in the spring and summer, wildlife is often easier to spot because the vegetation dies back and animals congregate around water holes.

The chilly nights of winter also mean fewer mosquitoes, but you’ll need to bring layers to keep you warm during dawn game drives. For safaris in the Western Cape, the summer months are drier but coincide with the busy Christmas period and South Africa’s summer school holidays.

Get more travel inspiration, tips and exclusive offers sent straight to your inbox with our weekly newsletter.

When to go whale-watching in South Africa

Though whales and dolphins can be seen year-round off South Africa’s southern and eastern coasts, September and October are the peak cetacean-spotting months. Between June and November, southern right whales and humpbacks migrate to and from Antarctica to breed and have their babies in the warmer waters off Mozambique and Madagascar. May to June also sees a massive run of sardines that attracts whales, dolphins, sharks and sea birds (Durban is a good base to watch the spectacle).

While you’ll see more from a whale-watching boat, whales often come close enough to the shore to be spotted from land. This is particularly so near the town of Hermanus, celebrated by the World Wildlife Fund as one of the world’s top whale-watching destinations, where whales can be seen as early as April. Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth) on the Eastern Cape is known as the world bottlenose dolphin capital, and pods are frequently seen between January and June.

The winter is the best time for wildlife encounters, but animals can be spotted year-round © moodboard / Getty Images

High Season (November to March) is the top time for festivals

November to March is summertime in South Africa with daytime highs reaching 32°C (90°F), often with quite a lot of humidity. If you’re looking to visit during this peak season, you’ll need to plan ahead. Accommodation in coastal areas and national parks can book up months in advance, and popular vacation spots see accommodation prices rise by 50% or more.

That said, if you have the budget to travel in the high season, you can enjoy a host of festivals and events. AFROPUNK, a massive international multi-day music festival that draws artists from all over the world, kicks off in December. Held annually on January 2, the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival (known locally as Kaapse Klopse) is a high-spirited street parade dating from the mid-1800s with important links to overcoming apartheid and South Africa’s long history of slavery.

Cape Town’s Pride Festival is held in late February or early March, followed by the Cape Town Cycle Tour which brings in cycling enthusiasts from all over the globe. March also sees the Cape Town International Jazz Festival and Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees, one of South Africa’s largest arts festivals, held at Oudtshoorn in the Western Cape.

Shoulder Season (April, May, September and October) brings lower prices and great wildlife watching

South Africa’s shoulder seasons see smaller crowds and several important festivals — including April’s Splashy Fen Music Festival in Durban. The big lure in the fall is wildlife-watching, as the tail end of the dry summer weather brings wildlife out into the open. The spring months of September and October bring the best chances of cetacean encounters. Wildflower season peaks in late August in the north and early September in the south, but blooms can appear from July depending on the rains and continue into October if it’s not too hot.

Low Season (June to August) is the best time for budget travelers

The South African winter from June to August brings lower prices (except for safaris) and smaller crowds. This is the rainy season in Cape Town and the Western Cape (with Cape Town restaurants often offering pocket-friendly winter specials), but there’s still plenty of sunshine around. Elsewhere in the country winters are much drier, and conditions are ideal for a safari (be prepared, though, for chilly nights and cold early morning game drives). Top winter festivals include the National Arts Festival in the Eastern Cape and Knysna’s 10-day Oyster Festival in July.

The rainy season in Cape Town and the Western Cape creates some impressive waterfalls © Franz Aberham / Getty Images

January

On either side of the New Year celebrations, South Africans descend on tourist areas, including the coast and national parks for the summer school holidays (early December to mid-January). Book accommodations and transport far in advance. The peak season for accommodations is November to March.

Key events: Cape Town Minstrel Carnival (Kaapse Klopse)

February

Summer continues through February, with hot weather, crowds basking happily on the southern beaches and, thanks to its subtropical climate and high elevation, dramatic lightning storms in Jo’burg. For something a little different, there’s the four-day Up the Creek Festival in Swellendam in the Western Cape, where you can float along the Breede River while bands play on the river’s banks.

Key events: Hands-on-Harvest, Up the Creek Festival, Ultra South Africa, Cape Town Pride Week

March

The summer rolls toward fall, but days are still sunny in the Cape. The Lowveld (open grassland and woodland areas between 150m and 610m above sea level) is steamy and warm, and the landscapes are lush and green; the Highveld, at higher altitude, is slightly cooler. This time of year is especially good for walking and beach bumming in the Western Cape. Cultural and music festivals happen in Cape Town and Jo’burg.

Key events: Cape Town Cycle Tour, Cape Town International Jazz Festival, Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees

April

There’s a two-week school vacation around Easter, generally regarded as the beginning of the short fall season; accommodations need to be booked well in advance. Days are still warm and nights begin to cool. Much of South Africa sees the end of the rainy season, with rivers full and flora lush.

Though you can still lie on the beach, the drier weather makes wildlife-watching in the bushveld a more attractive option. The rutting season for impala — one of South Africa’s most abundant antelopes — begins in April, with displays of dominance (like the clashing of horns) increasing as the days get shorter.

Key events: AfrikaBurn

The months immediately after the rains are a great time for trekking in the Drakensberg mountains © Gallo Images / Getty Images

In the first official month of winter, nighttime temperatures drop, and tourism slows. It’s still beach weather in Durban and along the KwaZulu-Natal coast, but snow may fall in the highlands. The end of the rains in most parts of the country means safari conditions start to improve.

Key events: Franschhoek Literary Festival

Winter brings cooling temperatures and – especially in Cape Town and the Western Cape – a good chance of rain. June is the coldest month in Johannesburg, with daytime temperatures around 16°C (60°F), falling to about 4°C (40°F) at night. Don’t let that put you off: safari conditions are still great in the dry north.

Key events: National Arts Festival

Winter brings rain to the Cape and clouds to Table Mountain (there’s even a chance you might get snow), but plenty of days will see some sunshine. Rougher winter seas make boat trips (even to Robben Island, the former political prison just off Cape Town) less pleasant, and trips may be canceled altogether during squalls.

Northern areas experience fresh, sunny days and clear night skies. Early winter mornings can be cold with temperatures close to freezing, but afternoon highs can creep up towards 18°C (65°F). This is the middle of the June to September low season (apart from the mid-June to mid-July school holidays), but winter is a great time for safaris.

Key events: Knysna Oyster Festival, J-Bay Open, Durban International Film Festival

August

Signs of spring are in the air in South Africa in August. Head to the west coast and the north to see wildflowers: mid-August to mid-September is usually the best time. Kruger National Park and the northern reserves remain pleasantly dry, and the soccer, rugby and cricket seasons typically begin in August.

Key events: Namakwa wildflowers

September

In September, the rainy season in the Western Cape eases off, and Jo’burg and the north often see their first big rains. Temperatures in Cape Town and Jo’burg are mild; cherry trees bloom in the south, and wildflowers reach their peak in mid-September. Safari parks remain a top draw with many baby animals born in spring. School holidays run from late September to early October, increasing demand for accommodation. It’s also a good time for whale-watching at Hermanus.

Key events: Festival of Motoring Johannesburg, Winelands Chocolate Festival, Hermanus Whale Festival

October

October offers mostly sunny weather but you’ll avoid the worst of the summer crowds and peak prices. Book accommodations in advance during the 10-day South African school holiday beginning in late September and stretching into early October. Whale-watching can be excellent at this time of year.

Key events: Macufe African Cultural Festival, Durban Bierfest

November

As spring drifts into summer, it’s the peak time to see grassland wildflowers in the Drakensberg mountains and the end of whale season off the Cape. Free State’s Ficksburg, known as Cherry Town, has a cherry-centered festival during the third week of November.

The rain and humidity start to increase around Kruger and in KwaZulu-Natal. It’s no longer cold but not uncomfortably hot in the semi-arid desert of Karoo National Park, with highs around 27°C (80°F) and lows around 10°C (50℉). November is when the high season begins, so expect higher prices and crowds.

Key events: Kirstenbosch Summer Sunset Concerts, Ficksburg Cherry Festival

December

The hot, dry days pick up as the South African summer officially gets cooking in December. Music festival AFROPUNK in Johannesburg is the perfect big-time kickoff to the city’s music festival season, while Durban celebrates its street food scene and craft distilleries with the annual Street Food Festival.

Key events: AFROPUNK, Durban Street Food Festival

This article was first published March 2021 and updated January 2022

Buy Epic Hikes of the World

With stories of 50 incredible hiking routes in 30 countries, from New Zealand to Peru, plus a further 150 suggestions, this book will inspire a lifetime of adventure on foot.

Buy Epic Hikes of the World

With stories of 50 incredible hiking routes in 30 countries, from New Zealand to Peru, plus a further 150 suggestions, this book will inspire a lifetime of adventure on foot.

Explore related stories

How to get around in South Africa

It’s the ninth biggest country in Africa, so here are the top tips for traveling around South Africa by air, rail or road.

19 best places to visit in South Africa

South Africa is a blend of peoples and cultures that is instantly evident, and the country’s diversity stretches to its incredible cities and landscapes.

Do you need a visa to go to South Africa?

Tourists from countries including the US, UK and Canada do not need a visa to visit South Africa, but do require some documentation. Find out more here.

South Africa’s wild gold rush road

Follow the trail of fortune-hunters through the mountains and end with animal encounters on one of the country’s original safaris.

Electronic visas are coming to South Africa

Between the long flight times and the requisite visas, reaching South Africa can be a tricky proposition for intercontinental travellers, but it’s about to get a bit easier – for some people, at least.

Best things to do in Cape Town in June

When June rolls around, Capetonians tend to wrap up and hibernate, sheltering from the winter rains. To entice them out of their homes, restaurants and…

Cape Town: take a walk, join a street party

Cape Town is embracing its pedestrian-friendly side like never before with the regular First Thursdays, Thursday Late and Open Streets events as well as…

Cape Town unleashes its inner ‘design diva’

At the start of the year Cape Town became the first African city to assume the mantle of World Design Capital (www.wdccapetown2014.com), an accolade…

Alternatives to Oktoberfest

The barrels may have already been rolled out at Munich’s annual Oktoberfest, but there are still plenty of other beer festivals happening all over the…

The Mason-Dixon Line: What Is It? Where is it? Why is it Important?

The British men in the business of colonizing the North American continent were so sure they “owned whatever land they land on” (yes, that’s from Pocahontas), they established new colonies by simply drawing lines on a map.

Then, everyone living in the now-claimed territory, became a part of an English colony.

And of all the lines drawn on maps in the 18th century, perhaps the most famous is the Mason-Dixon Line.

Table of Contents

What is the Mason-Dixon Line?

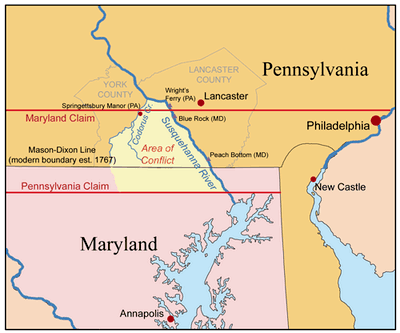

The Mason-Dixon Line also called the Mason and Dixon Line is a boundary line that makes up the border between Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. Over time, the line was extended to the Ohio River to make up the entire southern border of Pennsylvania.

But it also took on additional significance when it became the unofficial border between the North and the South, and perhaps more importantly, between states where slavery was allowed and states where slavery had been abolished.

Where is the Mason-Dixon Line?

For the cartographers in the room, the Mason and Dixon Line is an east-west line located at 39º43’20” N starting south of Philadelphia and east of the Delaware River. Mason and Dixon resurveyed the Delaware tangent line and the Newcastle arc and in 1765 began running the east-west line from the tangent point, at approximately 39°43′ N.

For the rest of us, it’s the border between Maryland, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The Pennsylvania–Maryland border was defined as the line of latitude 15 miles (24 km) south of the southernmost house in Philadelphia.

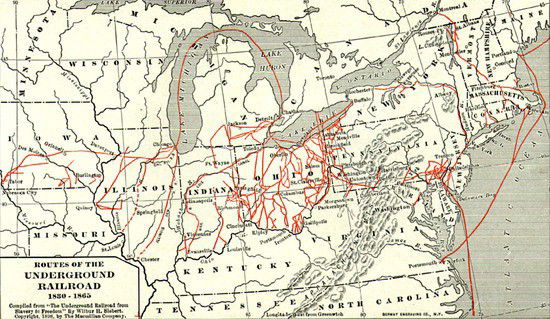

Mason-Dixon Line Map

Take a look at the map below to see exactly where the Mason Dixon Line is:

Why Is it Called the Mason-Dixon Line?

It is called the Mason and Dixon Line because the two men who originally surveyed the line and got the governments of Delaware, Pennsylvania and Maryland to agree, were named Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon.

Jeremiah was a Quaker and from a mining family. He showed a talent early on for maths and then surveying. He went down to London to be taken on by the Royal Society, just at a time when his social life was getting a bit out of hand.

He was a bit of a lad by all accounts, not your typical Quaker, and never married. He enjoyed socialising and carousing and was actually expelled from the Quakers for his drinking and keeping loose company.

Mason’s early life was more sedate by comparison. At the age of 28 he was taken on by the Royal Observatory in Greenwich as an assistant. Noted as a “meticulous observer of nature and geography” he later became a fellow of the Royal Society.

Mason and Dixon arrived in Philadelphia on 15 November 1763. Although the war in America had concluded some two years earlier, there remained considerable tension between the settlers and their native neighbours.

The line was not called the Mason-Dixon Line when it was first drawn. Instead, it got this name during the Missouri Compromise, which was agreed to in 1820.

It was used to reference the boundary between states where slavery was legal and states where it was not. After this, both the name and its understood meaning became more widespread, and it eventually became part of the border between the seceded Confederate States of America and Union Territories.

Why Do We Have a Mason-Dixon Line?

In the early days of British colonialism in North America, land was granted to individuals or corporations via charters, which were given by the king himself.

However, even kings can make mistakes, and when Charles II granted William Penn a charter for land in America, he gave him territory that he had already granted to both Maryland and Delaware! What an idiot!?

William Penn was a writer, early member of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the English North American colony the Province of Pennsylvania. He was an early advocate of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful treaties with the Lenape Native Americans.

Under his direction, the city of Philadelphia was planned and developed. Philadelphia was planned out to be grid-like with its streets and be very easy to navigate, unlike London where Penn was from. The streets are named with numbers and tree names. He chose to use the names of trees for the cross streets because Pennsylvania means “Penn’s Woods”.

But in his defense, the map he was using was inaccurate, and this threw everything out of whack. At first, it wasn’t a huge issue since the population in the area was so sparse there were not many disputes related to the border.

But as all the colonies grew in population and sought to expand westward, the matter of the unresolved border became a much more prominent in mid-Atlantic politics.

The Feud

In colonial times, as in modern times, too, borders and boundaries were critical. Provincial governors needed them to ensure they were collecting their due taxes, and citizens needed to know which land they had a right to claim and which belonged to someone else (of course, they didn’t seem to mind too much when that ‘someone else’ was a tribe of Native Americans).

The dispute had its origins almost a century earlier in the somewhat confusing proprietary grants by King Charles I to Lord Baltimore (Maryland) and by King Charles II to William Penn (Pennsylvania and Delaware). Lord Baltimore was an English nobleman who was the first Proprietor of the Province of Maryland, ninth Proprietary Governor of the Colony of Newfoundland and second of the colony of Province of Avalon to its southeast. His title was “First Lord Proprietary, Earl Palatine of the Provinces of Maryland and Avalon in America”.

A problem arose when Charles II granted a charter for Pennsylvania in 1681. The grant defined Pennsylvania’s southern border as identical to Maryland’s northern border, but described it differently, as Charles relied on an inaccurate map. The terms of the grant clearly indicate that Charles II and William Penn believed the 40th parallel would intersect the Twelve-Mile Circle around New Castle, Delaware, when in fact it falls north of the original boundaries of the City of Philadelphia, the site of which Penn had already selected for his colony’s capital city. Negotiations ensued after the problem was discovered in 1681.

As a result, solving this border dispute became a major issue, and it became an even bigger deal when violent conflict broke out in the mid-1730s over land claimed by both people from Pennsylvania and Maryland. This little event became known as Cresap’s War.

To stop this madness, the Penns, who controlled Pennsylvania, and the Calverts, who were in charge of Maryland, hired Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to survey the territory and draw a boundary line to which everyone could agree.

But Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon only did this because the Maryland governor had agreed to a border with Delaware. He later argued the terms he signed to were not the ones he had agreed to in person, but the courts made him stick to what was on paper. Always read the fine print!

This agreement made it easier to settle the dispute between Pennsylvania and Maryland because they could use the now established boundary between Maryland and Delaware as a reference. All they had to do was extend a line west from the southern boundary of Philadelphia, and…

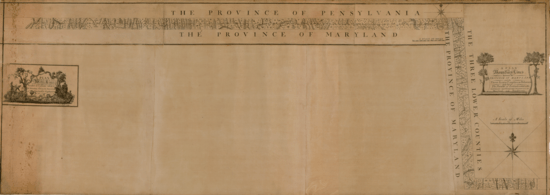

The Mason-Dixon Line was born.

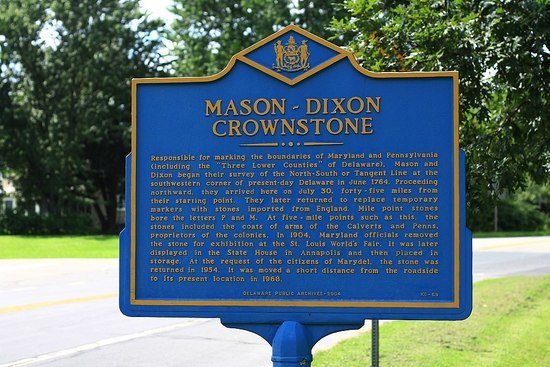

Limestone markers measuring up to 5ft (1.5m) high – quarried and transported from England – were placed at every mile and marked with a P for Pennsylvania and M for Maryland on each side. So-called Crown stones were positioned every five miles and engraved with the Penn family’s coat of arms on one side and the Calvert family’s on the other.

Later, in 1779, Pennsylvania and Virginia agreed to extend the Mason-Dixon Line west by five degrees of longitude to create the border between the two colines-turned-states (By 1779, the American Revolution was underway and the colonies were no longer colonies).

In 1784, surveyors David Rittenhouse and Andrew Ellicott and their crew completed the survey of the Mason–Dixon line to the southwest corner of Pennsylvania, five degrees from the Delaware River.

Rittenhouse’s crew completed the survey of the Mason–Dixon line to the southwest corner of Pennsylvania, five degrees from the Delaware River. Other surveyors continued west to the Ohio River. The section of the line between the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania and the river is the county line between Marshall and Wetzel counties, West Virginia.

In 1863, during the American Civil War, West Virginia separated from Virginia and rejoined the Union, but the line remained as the border with Pennsylvania.

It’s updated several times throughout history, the most recent being during the Kennedy Administration, in 1963.

The Mason-Dixon Line’s Place in History

The Mason–Dixon line along the southern Pennsylvania border later became informally known as the boundary between the free (Northern) states and the slave (Southern) states.

It is unlikely that Mason and Dixon ever heard the phrase “Mason–Dixon line”. The official report on the survey, issued in 1768, did not even mention their names. While the term was used occasionally in the decades following the survey, it came into popular use when the Missouri Compromise of 1820 named “Mason and Dixon’s line” as part of the boundary between slave territory and free territory.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was United States federal legislation that stopped northern attempts to forever prohibit slavery’s expansion by admitting Missouri as a slave state in exchange for legislation which prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel except for Missouri. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

At first glance, the Mason and Dixon Line doesn’t seem like much more than a line on a map. Plus, it was created out of a conflict brought on by poor mapping in the first place…a problem more lines aren’t likely to solve.

But despite its lowly status as a line on a map, it eventually gained prominence in United States history and collective memory because of what it came to mean to some segments of the American population.

It first took on this meaning in 1780 when Pennsylvania abolished slavery. Over time, more northern states would do the same until all the states north of the line did not allow slavery. This made it the border between slave states and free states.

Perhaps the biggest reason this is significant has to do with the underground resistance to slavery that took place almost from the institution’s inception. Slaves who managed to escape from their plantations would try to make their way north, past the Mason-Dixon Line.

However, in the early years of United States history, when slavery was still legal in some Northern states and fugitive slave laws required anyone who found a slave to return him or her to their owner, meaning Canada was often the final destination. Yet it was no secret the journey got slightly easier after crossing the Line and making it into Pennsylvania.

Because of this, the Mason-Dixon Line became a symbol in the quest for freedom. Making it across significantly improved your chances of making it to freedom.

Today, the Mason-Dixon Line does not have the same significance (obviously, since slavery is no longer legal) although it still serves as a useful demarcation in terms of American politics.

The “South” is still considered to start below the line, and political views and cultures tend to change dramatically once past the line and into Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, and so on.

Beyond this, the line still serves as the border, and anytime two groups of people can agree on a border for a long time, everyone wins. There’s less fighting and more peace.

The Line and Social Attitudes

Because when studying the United States history the most racist stuff always comes from the South, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking the North was as progressive as the South was racist.

But this simply isn’t true. Instead, people in the North were just as racist, but they went about it in different ways. They were more subtle. Sneakier. And they were quick to judge Southern racist, pushing attention away from them.

In fact, segregation still existed in many northern cities, especially when it came to housing, and attitudes towards blacks were far from warm and welcoming. Boston, a city very much in the North, has had a long history of racism, yet Massachusetts was one of the first states to abolish slavery.