Southern Dispersal Route: When Did Early Modern Humans Leave Africa?

Where has Homo sapiens come from?

We – people – are so different! Black, yellow and white, tall and short, dark-haired and fair-haired, brilliant and not very bright… Yet all of us – a blue-eyed Scandinavian giant, a dark-skinned pigmy from the Andaman Islands, and a tawny nomad from the African Sahara – belong to the same and sole mankind. And this is not a poetic figure of speech but a fact established by science and supported by the latest research in molecular biology. But where shall we look for the source of this many-faced living ocean? When, where and how did the first human being appear on the earth? Amazingly, even in our enlightened time, almost half citizens of the USA and a large share of Europeans vote for the divine origin, and many of the others believe in extraterrestrial interference, which, in fact, is not too different from the Divine Providence. However, even a firm advocate of evolution cannot give an unambiguous answer to this question

“A man has no reason to be ashamed of having an

ape for his grandfather. If there was an ancestor whom

I should feel shame in recalling it would rather be a man — a

man of restless and versatile intellect — who

not content with an equivocal success in his own sphere

of activity, plunges into scientific questions with which

he has no real acquaintance.”

Thomas Huxley (1869)

Not everybody knows that the non-Biblical version of human origin is rooted in the hazy 1600s, when the works of the Italian philosopher Lucilio Vanini and the English lord, barrister and theologian Mathew Hale, with the speaking titles On the Primitive Origin of Man (1615) and The Primitive Origin of Mankind, Considered and Examined According to the Light of Nature (1671), were published.

The baton passed by the philosophers who acknowledged the kinship of humans and apes was taken up in the 18th c. by the French diplomat B. de Mallier, and then by James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, who put forward the idea of the common descent of all the anthropoids, including man and chimpanzee. The French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, in his voluminous Histoire Naturelle, published a century before Ch. Darwin’s scientific bestseller The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), boldly asserted that man had originated from an ape.

In summary, by the late 19th century, the idea of man as a product of a long evolution of more primitive anthropoid beings had germinated and ripened. Moreover, in 1863 the German biologist and evolutionist Ernst Haeckel even classified the hypothetical being, the intermediate link between man and the ape, as Pithecanthropus alatus, i.e., an ape-human devoid of speech (from the Greek pinthecos, ape, and anthropos, man). Just one small thing was lacking – to discover this pithecantropos “in flesh,” which was done in the early 1890s by the Dutch anthropologist Eugene Dubois, who found the remains of a primitive hominin on the island of Java.

Since that time, the planet Earth has been recognized as an official place of residence of the early man, and another issue, as topical and controversial as man’s descent from apelike ancestors, was placed on the agenda: geographical centers and development of anthropogenesis. Thanks to the amazing discoveries made in the recent decades by the cooperative efforts of archaeologists, anthropologists, and specialists in paleogenetics, the problem of the development of the modern human, like in the days of Darwin, has generated a lot of public interest and moved beyond mere scientific debates.

African cradle

The history of the search for the ancestral homeland of the modern human, a plot with many twists full of astonishing discoveries, looked at first like a list of anthropological findings. In the first place, natural scientists became interested in the Asian continent including Southeast Asia, where Dubois discovered the osseous remains of the first hominin, later called Homo erectus. Then, in the 1920s—1930s, archaeologists found numerous fragments of the skeletons of 44 individuals who lived in Zhoukoudian Cave in Northern China, Central Asia, 460,000—230,000 years ago. These people, referred as Sinanthropuses, were once considered the oldest link in human genealogy.

Gradually, however, Africa pretended to the title of “mankind’s cradle.” In 1925, in the Kalahari Desert, the fossil remains of a hominin called Australopithecus were discovered; in subsequent 80 years, hundreds of similar remains, aged from 1.5 to 7 million years, were found in the south and east of the continent.

In the history of science you can hardly find a more exciting and controversial problem that would stir up common interest than the problem of life origin and development of its intellectual peak – humanity

In the Great Rift Valley, running from the Dead Sea depression through the Red Sea and on through Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania, more ancient sites were discovered with stone artifacts of the Oldowan Industry (choppers, choppings, roughly retouched flakes, etc). Excavations in the basin of the Kada Gona river led to the discovery, under a layer of tuff 2.6 Ma old, of more than 3000 primitive stone tools made by the first representative of the Homo genus – Homo habilis.

Mankind has become much older – it became evident that at least 6—7 Ma ago the common evolution tree split into two separate branches: anthropoid apes and Australopithecus, and the latter marked the beginning of the new, “sensible,” development path. The world’s oldest fossil remains of modern people – Homo sapiens, who appeared about 200,000—150,000 years ago – were also discovered in Africa. In this way, by the 1990s, the Recent African origin model, supported by recent genetic studies of various human populations, became universally accepted.

However, in between the two extreme reference points – the most ancient ancestors of humans and modern mankind – there is at least six million years during which the man not only developed his present look but also occupied virtually the whole territory of the planet fit for living. If Homo sapiens first appeared only in the African part of the world, when and how did he settle on the other continents?

Three exoduses

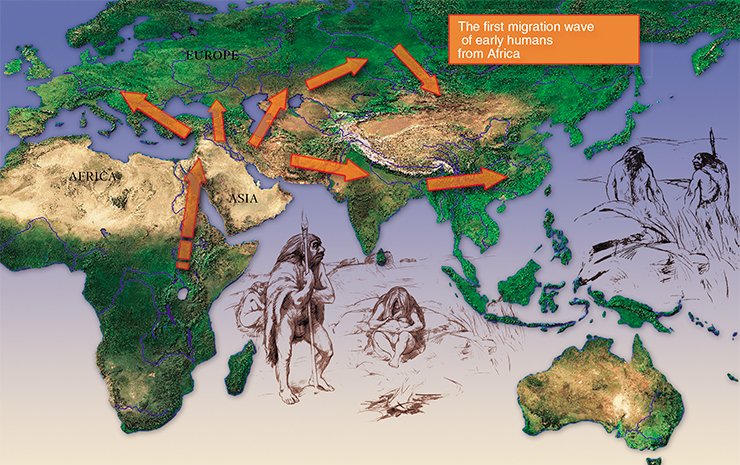

About 1.8—2.0 Ma years ago, the ancient ancestor of modern humans – Homo erectus or close to it Homo ergaster – first left Africa and began his conquest of Eurasia. This was the beginning of the first Migration Period, a long gradual process that took hundreds of millenniums and which can be traced by the fossil remains and typical tools of ancient stone industry.

The first migration flow of the oldest populations of hominins branched into two main directions, northward and eastward. The former went through the Near East and Iranian Plateau towards the Caucasus (and, probably, Asia Minor) and on to Europe. This is evidenced by the oldest Paleolithic localities in Dmanisi, East Georgia, and Atapuerca, Spain, dated 1.7—1.6 and 1.2—1.1 Ma, respectively.

In the east, an early testimony of human presence is pebble tools dated 1.65—1.35 Ma, found in the caves of South Arabia. Further migration to the east took two paths: the northern way went to Central, and the southern way went to East and Southeast Asia across the territory of modern Pakistan and India. Judging by the dating of the deposits of quarzitic tools in Pakistan (1.9 Ma) and China (1.8—1.5 Ma) and of the anthropological findings in Indonesia (1.8—1.6 Ma), the early hominins settled on the expanses of South, Southeast and East Asia not later than 1.5 million years ago. On the border of Central and North Asia, in Altai, South Siberia, an early Paleolithic Karama site was discovered – its deposits contained four layers with an archaic pebble industry aged 800,000—600,000 years.

All the oldest sites of Eurasia left by the first wave migration had pebble tools characteristic of the most ancient Oldowan Industry. About the same time or a little later, representatives of other early hominines came from Africa to Eurasia. They were carriers of a microlithic stone industry, where small tools dominated, and they took virtually the same ways as their predecessors. These two oldest technologies of stone working played the key role in the development of ancient tool making.

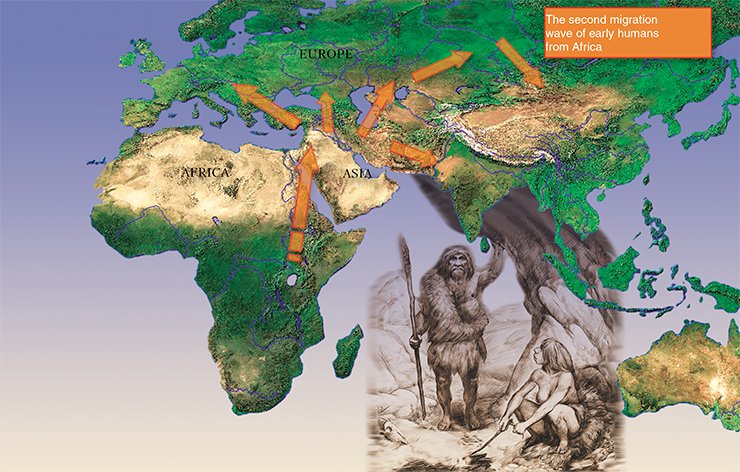

The second global wave of African migration spread to Near East about 1.5 Ma ago. Who were these new migrants? Probably, Homo heidelbergensis – a new type of people that combined both Neanderthal and sapiental features. A distinguishing feature of “new Africans” was stone tools of Acheulean industry made using more advanced stone working technologies – the so-called Levallois technique of stone knapping and methods for bilateral working of stone on both sides. Moving to the east, this wave met the descendants of the first wave hominines, which involved a mix of the two industries, pebble tool and Late Acheulean.

So far, not many osseous remains of primitive humans have been found. The bulk of material accessible to archaeologists is stone tools. From them, they can trace how the stone working techniques improved and human intellectual abilities developed

Approximately 600,000 years ago, these migrants of African descent reached Europe, where the Neanderthals – the type closest to modern humans – later developed. About 450,000—350,000 years ago, the bearers of Acheulean tradition penetrated the east of Eurasia, reaching India and Central Mongolia but they did not go as far as the eastern and southeastern regions of Asia.

The third exodus from Africa is related to the anatomically modern humans, who came to the evolutionary arena 200,000—150,000 years ago, as it was mentioned earlier. It is supposed that about 80,000—60,000 years ago, Homo sapiens, traditionally believed to be the bearer of Upper Paleolithic culture, began settling on other continents: first in the eastern part of Eurasia and Australia and then, in Central Asia and Europe.

Now we have approached the most dramatic and controversial part of our story. Genetic research has proved that all modern mankind descends from the same species of Homo sapiens, provided that mythical creatures like Yeti are disregarded. Then what happened to ancient human populations, descendants of the first and second migration waves from Africa, who lived in Eurasia for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years? Did they leave a trace in the evolutionary history of our species and if yes, how important was their contribution to modern humanity?

Depending on the answer to this question researchers can be divided in two groups, monocentrists and polycentrists.

Two models of anthropogenesis

In the end of the last century, the monocentric point of view on the appearance of Homo sapiens ultimately prevailed – the hypothesis of the African “exodus,” according to which the only ancestral home of Homo sapiens is the “black continent,” from where he settled all around the world. Basing on the results of the study of genetic variability of modern people, its advocates suppose that 80,000 – 60,000 years ago there was a demographic explosion in Africa, and as a result of a sharp growth in the population and lack of food, a new migration wave swept over Eurasia. Failing to withstand competition with a more evolutionarily advanced species, other hominines existing at that time, such as the Neanderthals, fell out of the evolutionary race some 30,000 – 25,000 years ago.

Monocentrists have a variety of opinions on the progress of this process. Some believe that the new human populations exterminated or drove out the aboriginal populations to less comfortable regions, where their mortality grew, especially among children, and their birthrate dropped. Others do not rule out the possibility of occasionally long coexistence of the Neanderthals and modern humans (for example, in the southern Pyrenees), which could result in cultural diffusion and at times hybridization. According to the third point of view, acculturation and assimilation took place whereby the aboriginal population dissolved among the newcomers.

It is difficult to fully accept all these circumstances without convincing archaeological and anthropological evidence to support them. Even if we agree with the debatable presumption that the population grew very quickly, it is inexplicable why the migration flow did not spread initially across the nearby areas but went a long way off to the east, reaching Australia. As an aside comment, though Homo sapiens must have covered a distance of over 10,000 kilometers, so far no archaeological evidence has been discovered to prove it. Moreover, archaeological data suggest that in the period from 80,000 to 30,000 years ago no change occurred in the local stone industries of South, Southeast and East Asia, which should have happened in the event the newcomers actually replaced the aborigines.

This absence of “road” proofs has led to the version that Homo sapiens moved from Africa to the east of Asia along the sea coastline, which today is under the water together with all Paleolithic evidence. If this is true, however, African stone industry must have been almost the same on the islands of South-East Asia, while archaeological materials aged 60,000—30,000 years do not support this idea.

Today, the monocentric hypothesis has given no satisfactory answers to many other questions either. In particular, why did anatomically modern humans appear at least 150,000 years ago and the Upper Paleolithic culture, traditionally connected exclusively with Homo sapiens, almost 100,000 years later? Why this culture, which emerged virtually simultaneously in far-away regions of Eurasia, is not as homogenous as it should be expected in the case of a single carrier?

These “dark spots” in man’s history may be accounted for by another, polycentric concept. According to this hypothesis of interregional human evolution, Homo sapiens could develop both in Africa and on the vast expanses of Eurasia, inhabited at that time by Homo erectus. It is the continuous development of the ancient population in each region that explains, in the polycentrists’ opinion, the striking difference between the Upper Paleolithic cultures of Africa, Europe, East Asia and Australia. Even though from the standpoint of up-to-date biology the formation of the same species (strictly speaking) in such different and geographically remote areas is unlikely, it is possible that independent, parallel evolution of the primitive man into Homo sapiens, with his developed material and spiritual culture, was taking place there.

Below we will provide some archaeological, anthropological and genetic evidence to prove this thesis, connected with the evolution of the primitive population of Eurasia.

Homo orientalis

Judging by the numerous archaeological findings, approximately 1.5 Ma ago stone industry in East and Southeast Asia took a development path that was entirely different from the rest of Eurasia and Africa. Surprisingly, during more than a million years, tool-making technology in the Chinese-Malaysian zone did not undergo any marked change. Furthermore, as it was mentioned above, in the period of 80,000—30,000 years ago, when anatomically modern humans should have appeared here, no radical innovations took place: neither new stone working technologies nor new types of tools emerged.

As for the anthropological evidence, most of the known skeleton remains of Homo erectus were found in China and Indonesia. Despite some differences, they make up quite a homogenous group. Of special interest is the volume of the brain of Homo erectus (1152—1123 cm 3 ), found in the Yungxian District, China. Evidence of the advanced morphology and culture of these ancient people, who lived about a million years ago, is the stone tools discovered next to them.

The next link in the evolution of the Asian Homo erectus was found in Zhoukoudian caves, Northern China. This hominin similar to the Java pithecanthropus was classified in the Homo genus as a subspecies, Homo erectus pekinensis. Some anthropologists argue that all these remains of the earlier and more recent types of primitive people form a continuous evolutionary line extending almost up to Homo sapiens.

Thus, it can be taken for granted that over a span of more than a million years in East and Southeast Asia the Asian type of Homo erectus evolutionally developed independently from the rest of the world. This, however, does not rule out the possibility of migrations of small populations from the adjoining regions and, consequently, of genetic exchange. At the same time, the process of divergence that took place in these primitive humans themselves could have led to pronounced differences in morphology. An example is paleoanthropological discoveries from Java Island, which differ from the analogous Chinese findings of the same time: though Java hominin has preserved the primary features of Homo erectus, some characteristics of his were similar to these of Homo sapiens.

As a result, in the beginning of the Upper Pleistocene in East and Southeast Asia, on the basis of the local type of Homo erectus, a hominin anatomically close to a modern human formed. Supporting this view are the new datings of the Chinese paleoanthropological findings having the features of “sapiens,” according to which 100,000 years ago this region could have been inhabited by anatomically modern humans.

Neanderthals come back

The first representative of archaic people that became known to science is the Neanderthal, Homo neanderthalensis. The Neanderthals mostly lived in Europe but traces of their presence have also been discovered in Near East, West and Central Asia and in the south of Siberia. These short stumpy people, physically strong and well adapted to the severe conditions of the northern latitudes, in terms of the brain volume (1400 cm 3 ) were on a par with modern humans.

In a century and a half that have passed since the first Neanderthals’ remains were discovered, hundreds of their sites, settlements and burial grounds have been studied. It has turned out that these archaic people not only made quite advanced tools but exhibited some aspects of behavior typical of Homo sapiens. For instance, the well-known archaeologist A. P. Okladnikov in 1949, in Teshik-Tash Cave (Uzbekistan) discovered the tomb of a Neanderthal with the traces of what was presumably a ritual burial.

Prior to the beginning of the 21st century, many anthropologists classified the Neanderthals as an ancestral form of modern humans; however, after mitochondrial DNA from their remains was examined, they were treated as a dead end. The Neanderthals were considered to have been forced out and replaced by modern humans of African descent. Further anthropological and genetic studies have shown, however, that the relations between the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were not as simple as that. According to the latest evidence, up to 4 % of the modern humans’ (not Africans’) genome was borrowed from Homo neanderthalensis. Currently, there is no doubt that on the border of the areas populated by these humans not only cultural diffusion but also hybridization and assimilation took place.

Today, the Neanderthals are classified as a sister group of modern humans, and their status of “man’s ancestors” has been restored.

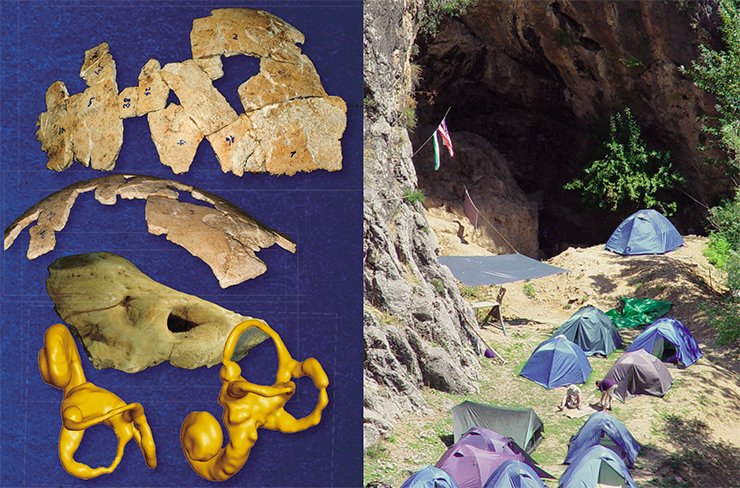

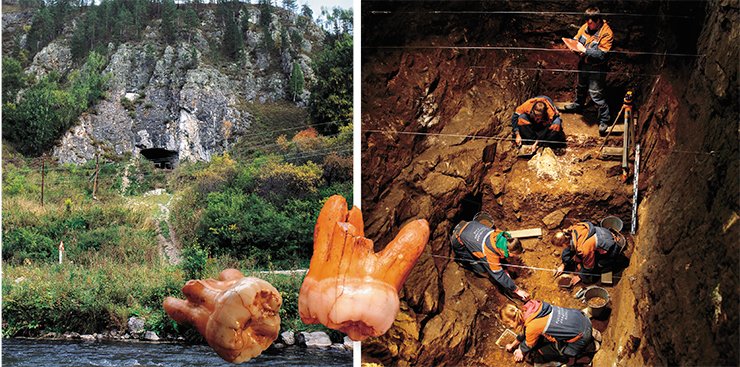

In the rest of Eurasia, the development of the Upper Paleolithic followed a different path. Let us trace this development through the example of Altai region, which has produced some astonishing results obtained with the help of the paleogenetic examination of the anthropological findings from Denisova and Okladnikov caves.

One more member for the club

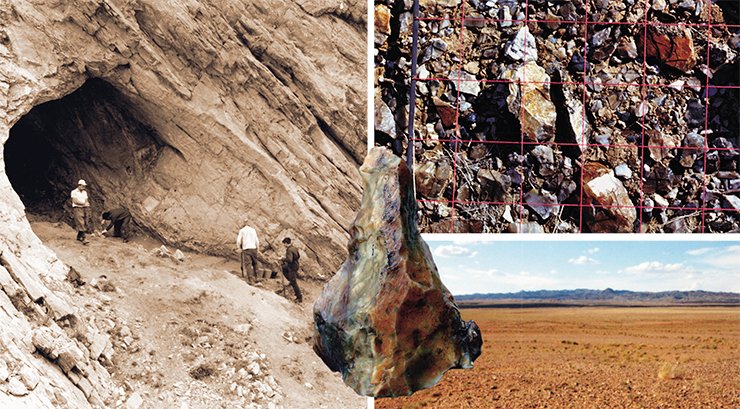

As mentioned earlier, man first came to Altai not later than 800,000 years ago, during the first migration wave from Africa. The uppermost occupation layer of the Paleolithic site of Karama in the Anui River Valley (the oldest site in the Asian part of Russia) formed about 600,000 years ago, after which the development of Paleolithic culture in this area took a long break. About 280,000 years ago, carriers of more advanced stone working techniques came to Altai, and since then Paleolithic culture developed continuously.

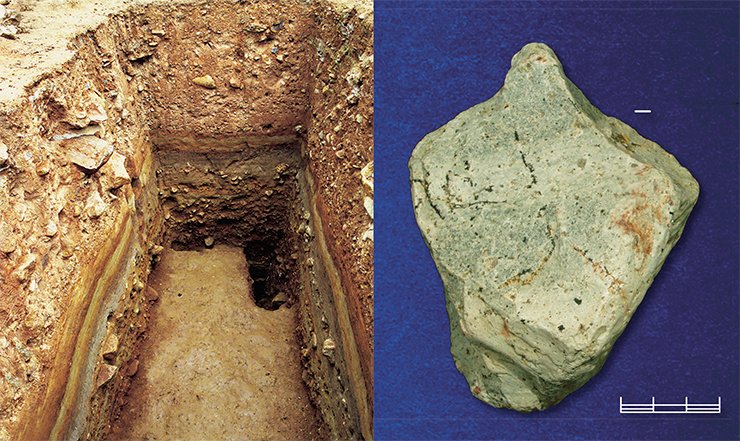

In Obi-Rakhmat Cave, Uzbekistan, stone tools dating back to the turning point – the Middle Paleolithic to the Upper Paleolithic transition – were discovered. Moreover, the fossil remains found here give a rare chance to restore the habitat of the humans who carried out technological and cultural revolution

In the last twenty-five years, about 20 sites located in the caves and on the slopes of valleys in the Altai Mountains have been studied, and over 70 occupation layers of the Early, Middle and Upper Paleolithic have been examined. For example, in Denisova Cave alone 13 Paleolithic layers were distinguished. The oldest findings, dated the early period of Middle Paleolithic, were discovered in the layer aged from 282,000 to 170,000 years; Middle Paleolithic artifacts were found in the layer dating back to between 155,000 and 50,000 BP, and the Upper Paleolithic findings were dated to between 50,000 and 20,000 years ago. This long and “continuous” chronicle allows us to trace the changes that occurred in stone artifacts in many tens of thousands of years. It has turned out that it was a gradual process, a step-by-step evolution without any external “perturbations” – innovations.

Archaeological data testify that as early as 50,000—45,000 years ago Upper Paleolithic era began in Altai, and the sources of the Upper Paleolithic cultural traditions can be easily traced back to the final stage of Middle Paleolithic. Artifacts supporting this statement are miniature bone needles with drilled eyes, pendants, beads and other non-utilitarian things made of bone, ornamental stone and clamshell, as well as the truly remarkable finds: fragments of a bracelet and a stone ring with traces of grinding, polishing and drilling.

Regretfully, Altai Paleolithic localities cannot boast of many anthropological findings. The most impressive are the teeth and skeleton fragments from two caves, Okladnikov and Denisova, were studied in the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany) by an international team of genetic scientists led by Professor Svante Pääbo.

Paleogenetic studies confirmed that the remains discovered in Okladnikov Cave were Neanderthal whereas the results of the sequencing of mitochondrial and then nuclear DNA from the bone samples discovered in the occupation layer of the Upper Paleolithic early stage in Denisova Cave sprang a surprise on the researchers. The bone fragments proved to belong to a new fossil hominin, unknown to science, who was given the name of Homo sapiens altaiensis, or Denisovan, after the locality where he was discovered.

A boy from the Stone Age

On that occasion, as always, Okladnikov was summoned.

— A bone.

He came up, bent over it and began brushing it carefully. And then his hand trembled. This was not just one bone, there were many of them. Fragments of a man’s skull. Heaven! Of a man! It was a find he had not dared to dream of.

Though could this person be buried here not long ago? It takes a few years for bones to decompose, and to expect that they will stay intact for dozens of millennia… Actually, it happens but very rarely. There is only a handful of such finds in the entire history of humankind.

But what if.

— Verochka!

He called his wife below his breath.

She came up and bent over.

— This is a skull, she whispered. — Look, it’s crushed.

The cranium was lying with the crown down. It must have been crushed by a falling clot of earth. The skull was small! A boy’s or a girl’s.

With a spade and a brush, Okladnikov began widening the dig. The spade hit against something hard. A bone. Another one, and one more…It was a small skeleton, the skeleton of a child. An animal must have found its way into the cave and picked the bones. They were scattered, some of them gnawed and bitten.

But when did this child live? In what years, centuries, millennia? If he was a young master of the cave when people who worked stone lived here … The thought was terrifying. If it was so, the child was Neanderthal. A man who lived tens of thousands or even a hundred thousand years ago. He must have a very pronounced brow ridge and no chin.

The easiest thing to do was to turn the cranium to have a better look but this would have disrupted the excavation plan. They had to complete the excavations around it leaving the child’s bones untouched. The dig around them will deepen, and the bones will remain as though lying on a pedestal.

Okladnikov consulted Vera Dmitrievna, and she agreed with him.

. The child’s bones were left untouched. They were even covered. The archaeologists dug around them, and the bones were on a ground pedestal, which became higher every day. It appeared to be growing from the underground.

The night before that memorable day Okladnikov had trouble falling asleep. He was lying on his back, hands behind his head, looking up at the black southern sky. Far above, the stars were swarming. They were so many that it seemed there was not enough room for all of them. That faraway world inspired awe and at the same time instilled serenity. You felt like thinking of life, eternity, the faraway past and the faraway future.

What could the ancient man be thinking about when he was looking up at the sky? It was the same as it is now. Maybe, sometimes he also had trouble falling asleep, was lying in the cave and looking up at the sky. Did he only have memories or did he have dreams as well? What was that man? The stones told a story but there were many things about which they remained quiet.

Life buries its traces deep underground. Overlaying them are new traces, which with time also go down. And so it happens century after century, millennium after millennium. Life puts layers of its past in the ground. Paging through them, an archaeologist can learn about the doings of the people who used to live here and to determine, virtually without mistake, the times when they lived.

Drawing the curtain above the past, they removed land layer by layer, as time had put them.”

The genome of the Denisovans differs from the reference genome of a modern African by 11.7 %, and that of the Neanderthal from Vindija Cave, Croatia, by 12.2 %. This similarity testifies that the Neanderthals and Denisovans are sister groups with the same ancestor, who branched off the man’s mainstream evolutionary trunk. These two groups separated approximately 640,000 years ago, taking the path of independent development. Another proof is that the Neanderthals share some genetic variants with modern Eurasians whereas some of the Denisovans’ genetic material was borrowed by the Melanesians and indigenous inhabitants of Australia, who stand apart from other non-African human populations.

Judging by the archaeological data, 50,000—40,000 years ago, in the northwestern region of Altai two different groups of primitive people lived next to each other: the Denisovans and the easternmost population of the Neanderthals, who came there at about the same time, probably from the territory of modern Uzbekistan. The roots of the culture whose carriers were the Denisovans can be traced back to the earliest sequences of Denisova Cave, as it was mentioned earlier. Interestingly, according to the panoply of archaeological findings reflecting the development of the Upper Paleolithic culture, the Denisovans were not only on a par with the anatomically modern humans inhabiting at that time other territories but in some respects were superior to them.

To sum up, during the Late Pleistocene there were at least two other forms of hominines in Eurasia: Neanderthal in the western part of the continent and Denisovan in the eastern. Taking into consideration the gene drift from the Neanderthals to Eurasians and from the Denisovans to the Melanesians, we can take it that both these groups have contributed to the formation of anatomically modern humans.

Taking into account all the available archaeological, anthropological, and genetic materials from the oldest localities of Africa and Eurasia, it can be presumed that the globe had several areas where Homo erectus populations and stone working technologies developed independently. Respectively, each of these areas generated its own cultural traditions and its own models for the transition from the Middle Paleolithic to the Upper Paleolithic.

Thus, the basis of the evolutionary sequence crowned with the anatomically modern humans is the ancestral form of Homo erectus sensu lato*. Probably, in the Late Pleistocene it ultimately developed into the humans of the anatomically and genetically modern species Homo sapiens including four forms that can be referred to as Homo sapiens africaniensis (East and South Africa), Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Europe), Homo sapiens orientalensis (Southeast and East Asia) and Homo sapiens altaiensis (North and Central Asia). In all likelihood, the idea to unite all these primitive people into a single species, Homo sapiens, can give rise to doubt and objections but it has to be remembered that it is based on a large body of analytical information, only a small part of which was given in this paper.

Evidently, not all of these subspecies have contributed equally to the formation of anatomically modern humans: Homo sapiens africaniensis featured the greatest genetic diversity, and it was he who laid the foundation for the modern human. However, the most recent data of paleogenetc research dealing with the presence of Neanderthal and Denisovan genes in the gene pool of modern mankind have shown that the other groups of ancient people did not stand back either.

Currently, archaeologists, anthropologists, experts in genetics and other specialists interested in human origin have accumulated an enormous number of new data basing on which new hypotheses, sometimes diametrically opposite, can be formulated. It is high time to discuss them in detail under the essential condition that man’s origin is a multidisciplinary problem and new ideas should be based on a complex study of the results obtained by the specialists of a wide variety of sciences. Only this way will ultimately give us the answer to one of the most controversial questions that has stirred people for centuries – the development of intelligence. According to Thomas Huxley quoted above, “each of our firmest convictions can be overthrown or, at least, revised by further successes in knowledge.”

* Homo erectus sensu lato – Homo erectus in a general sense

Derevjanko A. P. Drevnejshie migracii cheloveka v Evrazii v rannem paleolite. Novosibirsk: IAJeT SO RAN, 2009.

Derevjanko A. P. Perehod ot srednego k verhnemu paleolitu i problema formirovanija Homo sapiens sapiens v Vostochnoj, Central’noj i Severnoj Azii. Novosibirsk: IAJeT SO RAN, 2009.

Derevjanko A. P. Verhnij paleolit v Afrike i Evrazii i formirovanie cheloveka sovremennogo anatomicheskogo tipa. Novosibirsk: IAJeT SO RAN, 2011.

Derevjanko A. P., Shun’kov M. V. Rannepaleoliticheskaja stojanka Karama na Altae: pervye rezul’taty issledovanij // Arheologija, jetnografija i antropologija Evrazii. 2005. № 3.

Derevjanko A. P., Shun’kov M. V. Novaja model’ formirovanija cheloveka sovremennogo fizicheskogo vida // Vestnik RAN. 2012. T. 82. № 3. S. 202—212.

Derevjanko A. P., Shun’kov M. V., Agadzhanjan A. K. i dr. Prirodnaja sreda i chelovek v paleolite Gornogo Altaja. Novosibirsk: IAJeT SO RAN, 2003.

Derevjanko A. P., Shun’kov M. V. Volkov P. V. Paleoliticheskij braslet iz Denisovoj peshhery // Arheologija, jetnografija i antropologija Evrazii. 2008. № 2.

Bolikhovskaya N. S., Derevianko A. P., Shunkov M. V. The fossil palynoflora, geological age, and dimatostratigraphy of the earliest deposits of the Karama site (Early Paleolithic, Altai Mountains) // Paleontological Journal. 2006. V. 40. Р. 558–566.

Krause J., Orlando L., Serre D. et al. Neanderthals in Central Asia and Siberia // Nature. 2007. V. 449. Р. 902—904.

Krause J., Fu Q., Good J. et al. The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia // Nature. 2010. V. 464. P. 894—897.

Southern Dispersal Route: When Did Early Modern Humans Leave Africa?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/southern-dispersal2-57a9a6445f9b58974a0d9a15.png)

K. Kris Hirst is an archaeologist with 30 years of field experience. Her work has appeared in scholarly publications such as Archaeology Online and Science.

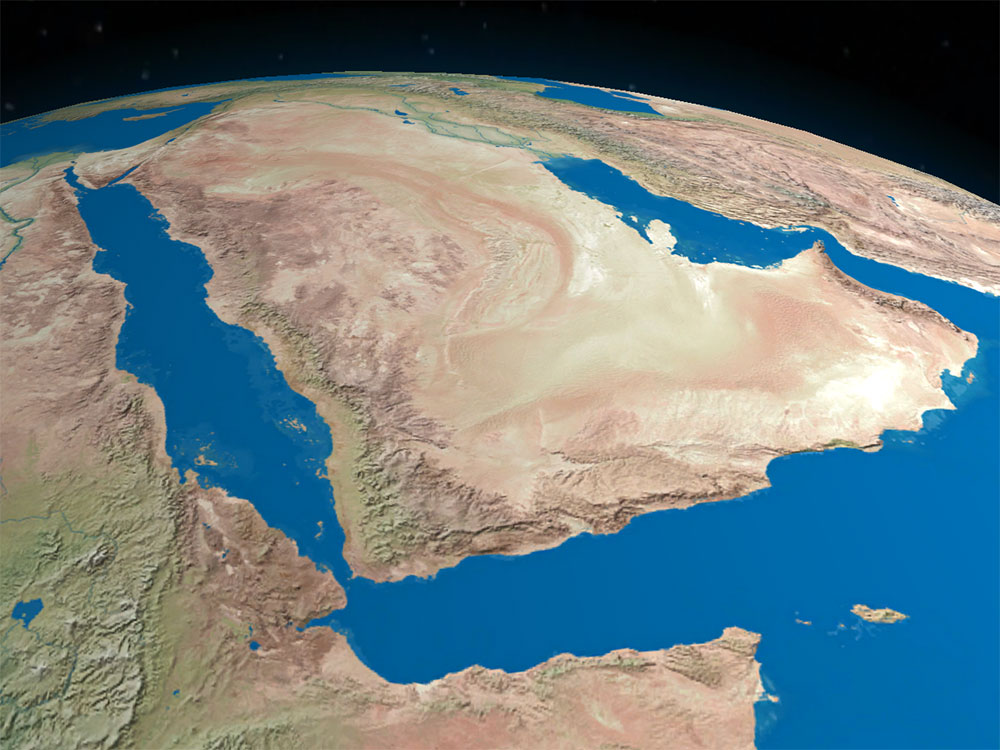

The Southern Dispersal Route refers to a theory that an early group of modern human beings left Africa between 130,000–70,000 years ago. They moved eastward, following the coastlines of Africa, Arabia, and India, arriving in Australia and Melanesia at least as early as 45,000 years ago. It is one of what appears now to have been multiple migration paths that our ancestors took as they left out of Africa.

Coastal Routes

Modern Homo sapiens, known as Early Modern Humans, evolved in East Africa between 200,000–100,000 years ago, and spread throughout the continent.

The main southern dispersal hypothesis starts 130,000–70,000 years ago in South Africa, when and where modern Homo sapiens lived a generalized subsistence strategy based on hunting and gathering coastal resources like shellfish, fish, and sea lions, and terrestrial resources such as rodents, bovids, and antelope. These behaviors are recorded at archaeological sites known as Howiesons Poort/Still Bay. The theory suggests some people left South Africa and followed the eastern coast up to the Arabian peninsula and then traveled along the coasts of India and Indochina, arriving in Australia by 40,000–50,000 years ago.

The notion that humans might have used coastal areas as pathways of migration was first developed by American geographer Carl Sauer in the 1960’s. Coastal movement is part of other migration theories including the original out of Africa theory and the Pacific coastal migration corridor thought to have been used to colonize the Americas at least 15,000 years ago.

Southern Dispersal Route: Evidence

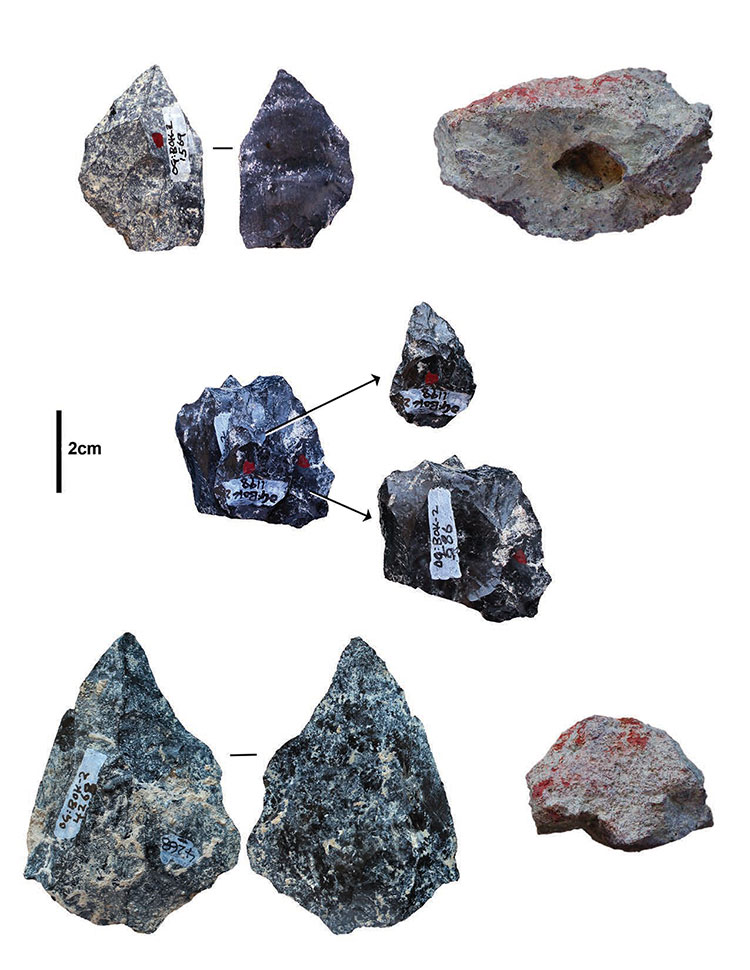

Archaeological and fossil evidence supporting the Southern Dispersal Route includes similarities in stone tools and symbolic behaviors at several archaeological sites throughout the world.

- South Africa: Howiesons Poort/Stillbay sites such as Blombos Cave, Klasies River Caves, 130,000–70,000

- Tanzania: Mumba Rock Shelter (~50,000–60,000)

- United Arab Emirates: Jebel Faya (125,000)

- India: Jwalapuram (74,000) and Patne

- Sri Lanka: Batadomba-lena

- Borneo: Niah Cave (50,000–42,000)

- Australia: Lake Mungo and Devil’s Lair

Chronology of the Southern Dispersal

The site of Jwalapuram in India is key to dating the southern dispersal hypothesis. This site has stone tools which are similar to Middle Stone Age South African assemblages, and they occur both before and after the eruption of the Toba volcano in Sumatra, which has recently been securely dated to 74,000 years ago. The power of the massive volcanic eruption was largely considered to have created a wide swath of ecological disaster, but because of the findings at Jwalapuram, the level of devastation has recently come under debate.

There were several other species of humans sharing planet earth at the same time as the migrations out of Africa: Neanderthals, Homo erectus, Denisovans, Flores, and Homo heidelbergensis). The amount of interaction Homo sapiens had with them during their sojourn out of Africa, including what role the EMH had with the other hominins disappearing from the planet, is still widely debated.

Stone Tools and Symbolic Behavior

Stone tool assemblages in Middle Paleolithic East Africa were primarily made using a Levallois reduction method, and include retouched forms such as projectile points. These types of tools were developed during Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 8, about 301,000-240,000 years ago. People leaving Africa took those tools with them as they spread eastward, arriving in Arabia by MIS 6–5e (190,000–130,000 years ago), India by MIS 5 (120,000–74,000), and in southeast Asia by MIS 4 (74,000 years ago). Conservative dates in southeast Asia include those at Niah Cave in Borneo at 46,000 and in Australia by 50,000–60,000.

The earliest evidence for symbolic behavior on our planet is in South Africa, in the form of the use of red ochre as paint, carved and etched bone and ochre nodules, and beads made from deliberately perforated sea shells. Similar symbolic behaviors have been found at the sites which make up the southern diaspora: red ochre use and ritual burials at Jwalapuram, ostrich shell beads in southern Asia, and widespread perforated shells and shell beads, hematite with ground facets, and ostrich shell beads. There is also evidence for the long distance movement of ochres—ochre was so important a resource it was sought and curated—as well as engraved figurative and non-figurative art, and composite and complex tools such as stone axes with narrow waists and ground edges, and adzes made of marine shell.

The Process of Evolution and Skeletal Diversity

So, in summary, there is growing evidence that people began to leave Africa beginning at least as early as the Middle Pleistocene (130,000), during a period when the climate was warming. In evolution, the region with the most diverse gene pool for a given organism is recognized as a marker of its point of origin. An observed pattern of decreasing genetic variability and skeletal form for humans has been mapped with distance from sub-Saharan Africa.

At the moment, the pattern of ancient skeletal evidence and modern human genetics scattered throughout the world best matches a multiple-event diversity. It seems that the first time we left Africa was from South Africa at least 50,000–130,000 then along and through the Arabian peninsula; and then there was a second outflow from East Africa through the Levant at 50,000 and then into northern Eurasia.

If the Southern Dispersal Hypothesis continues to stand up in the face of more data, the dates are likely to deepen: there is evidence for early modern humans in southern China by 120,000–80,000 bp.

An Evolutionary Timeline of Homo Sapiens

These five skulls, which range from an approximately 2.5-million-year-old Australopithecus africanus on the left to an approximately 4,800-year-old Homo sapiens on the right, show changes in the size of the braincase, slope of the face and shape of the brow ridges over just less than half of human evolutionary history. Human Origins Program, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution

The long evolutionary journey that created modern humans began with a single step—or more accurately—with the ability to walk on two legs. One of our earliest-known ancestors, Sahelanthropus, began the slow transition from ape-like movement some six million years ago, but Homo sapiens wouldn’t show up for more than five million years. During that long interim, a menagerie of different human species lived, evolved and died out, intermingling and sometimes interbreeding along the way. As time went on, their bodies changed, as did their brains and their ability to think, as seen in their tools and technologies.

To understand how Homo sapiens eventually evolved from these older lineages of hominins, the group including modern humans and our closest extinct relatives and ancestors, scientists are unearthing ancient bones and stone tools, digging into our genes and recreating the changing environments that helped shape our ancestors’ world and guide their evolution.

These lines of evidence increasingly indicate that H. sapiens originated in Africa, although not necessarily in a single time and place. Instead it seems diverse groups of human ancestors lived in habitable regions around Africa, evolving physically and culturally in relative isolation, until climate driven changes to African landscapes spurred them to intermittently mix and swap everything from genes to tool techniques. Eventually, this process gave rise to the unique genetic makeup of modern humans.

“East Africa was a setting in foment—one conducive to migrations across Africa during the period when Homo sapiens arose,” says Rick Potts, director of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program. “It seems to have been an ideal setting for the mixing of genes from migrating populations widely spread across the continent. The implication is that the human genome arose in Africa. Everyone is African, and yet not from any one part of Africa.”

New discoveries are always adding key waypoints to the chart of our human journey. This timeline of Homo sapiens features some of the best evidence documenting how we evolved.

550,000 to 750,000 Years Ago: The Beginning of the Homo sapiens Lineage

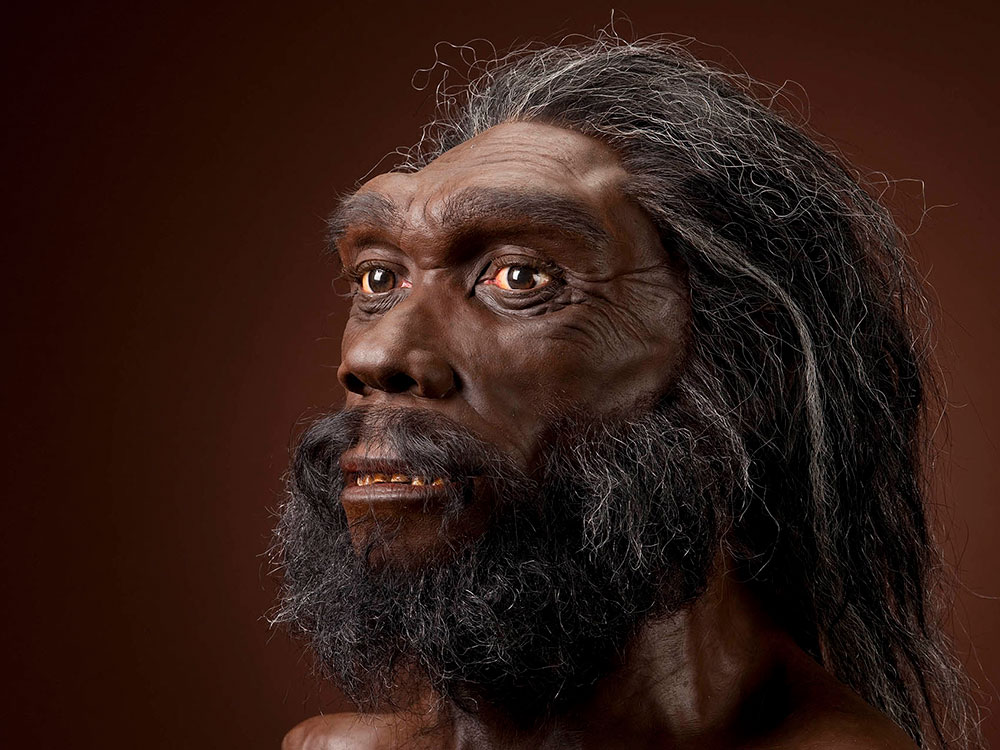

A facial reconstruction of Homo heidelbergensis, a popular candidate as a common ancestor for modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans John Gurche

Genes, rather than fossils, can help us chart the migrations, movements and evolution of our own species—and those we descended from or interbred with over the ages.

The oldest-recovered DNA of an early human relative comes from Sima de los Huesos, the “Pit of Bones.” At the bottom of a cave in Spain’s Atapuerca Mountains scientists found thousands of teeth and bones from 28 different individuals who somehow ended up collected en masse. In 2016, scientists painstakingly teased out the partial genome from these 430,000-year-old remains to reveal that the humans in the pit are the oldest known Neanderthals, our very successful and most familiar close relatives. Scientists used the molecular clock to estimate how long it took to accumulate the differences between this oldest Neanderthal genome and that of modern humans, and the researchers suggest that a common ancestor lived sometime between 550,000 and 750,000 years ago.

Pinpoint dating isn’t the strength of genetic analyses, as the 200,000-year margin of error shows. “In general, estimating ages with genetics is imprecise,” says Joshua Akey, who studies evolution of the human genome at Princeton University. “Genetics is really good at telling us qualitative things about the order of events, and relative time frames.” Before genetics, these divergence dates were estimated by the oldest fossils of various lineages scientists found. In the case of H. sapiens, known remains only date back some 300,000 years, so gene studies have located the divergence far more accurately on our evolutionary timeline than bones alone ever could.

Though our genes clearly show that modern humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans—a mysterious hominin species that left behind substantial traces in our DNA but, so far, only a handful of tooth and bone remains—do share a common ancestor, it’s not apparent who it was. Homo heidelbergensis, a species that existed from 200,000 to 700,000 years ago, is a popular candidate. It appears that the African family tree of this species leads to Homo sapiens while a European branch leads to Homo neanderthalensis and the Denisovans.

More ancient DNA could help provide a clearer picture, but finding it is no sure bet. Unfortunately, the cold, dry and stable conditions best for long-term preservation aren’t common in Africa, and few ancient African human genomes have been sequenced that are older than 10,000 years.

“We currently have no ancient DNA from Africa that even comes near the timeframes of our evolution—a process that is likely to have largely taken place between 800,000 and 300,000 years ago,” says Eleanor Scerri, an archaeological scientist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

300,000 Years Ago: Fossils Found of Oldest Homo sapiens

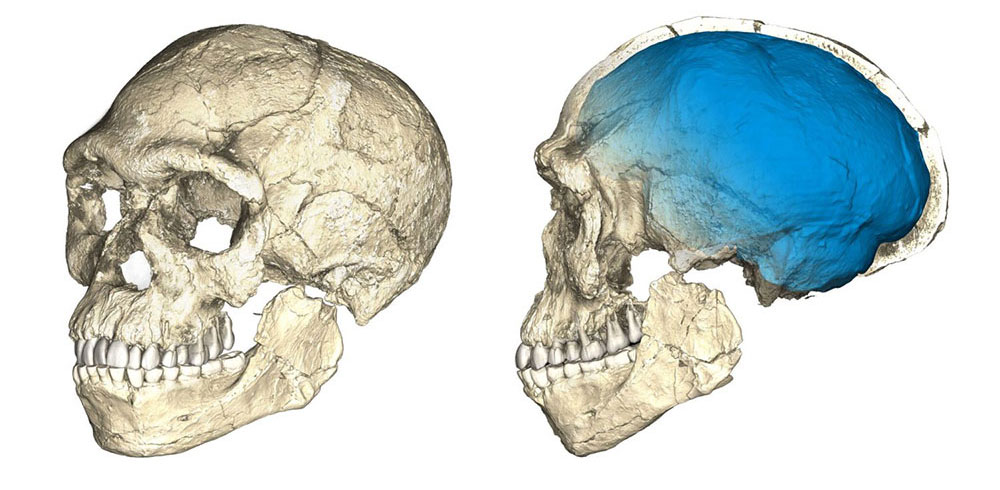

Two views of a composite reconstruction of the earliest known Homo sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud Philipp Gunz, MPI EVA Leipzig via CC-BY-SA 2.0

As the physical remains of actual ancient people, fossils tell us most about what they were like in life. But bones or teeth are still subject to a significant amount of interpretation. While human remains can survive after hundreds of thousands of years, scientists can’t always make sense of the wide range of morphological features they see to definitively classify the remains as Homo sapiens, or as different species of human relatives.

Fossils often boast a mixture of modern and primitive features, and those don’t evolve uniformly toward our modern anatomy. Instead, certain features seem to change in different places and times, suggesting separate clusters of anatomical evolution would have produced quite different looking people.

No scientists suggest that Homo sapiens first lived in what’s now Morocco, because so much early evidence for our species has been found in both South Africa and East Africa. But fragments of 300,000-year-old skulls, jaws, teeth and other fossils found at Jebel Irhoud, a rich site also home to advanced stone tools, are the oldest Homo sapiens remains yet found.

The remains of five individuals at Jebel Irhoud exhibit traits of a face that looks compellingly modern, mixed with other traits like an elongated brain case reminiscent of more archaic humans. The remains’ presence in the northwestern corner of Africa isn’t evidence of our origin point, but rather of how widely spread humans were across Africa even at this early date.

Other very old fossils often classified as early Homo sapiens come from Florisbad, South Africa (around 260,000 years old), and the Kibish Formation along Ethiopia’s Omo River (around 195,000 years old).

The 160,000-year-old skulls of two adults and a child at Herto, Ethiopia, were classified as the subspecies Homo sapiens idaltu because of slight morphological differences including larger size. But they are otherwise so similar to modern humans that some argue they aren’t a subspecies at all. A skull discovered at Ngaloba, Tanzania, also considered Homo sapiens, represents a 120,000-year-old individual with a mix of archaic traits and more modern aspects like smaller facial features and a further reduced brow.

Debate over the definition of which fossil remains represent modern humans, given these disparities, is common among experts. So much so that some seek to simplify the characterization by considering them part of a single, diverse group.

“The fact of the matter is that all fossils before about 40,000 to 100,000 years ago contain different combinations of so called archaic and modern features. It’s therefore impossible to pick and choose which of the older fossils are members of our lineage or evolutionary dead ends,” Scerri suggests. “The best model is currently one in which they are all early Homo sapiens, as their material culture also indicates.”

As Scerri references, African material culture shows a widespread shift some 300,000 years ago from clunky, handheld stone tools to the more refined blades and projectile points known as Middle Stone Age toolkits.

So when did fossils finally first show fully modern humans with all representative features? It’s not an easy answer. One skull (but only one of several) from Omo Kibish looks much like a modern human at 195,000 years old, while another found in Nigeria’s Iwo Eleru cave, appears very archaic, but is only 13,000 years old. These discrepancies illustrate that the process wasn’t linear, reaching some single point after which all people were modern humans.

300,000 Years Ago: Artifacts Show a Revolution in Tools

The two objects on the right are pigments used between 320,000 and 500,000 years ago in East Africa. All other objects are stone tools used during the same time period in the same area. Human Origins Program, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution

Our ancestors used stone tools as long as 3.3 million years ago and by 1.75 million years ago they’d adopted the Acheulean culture, a suite of chunky handaxes and other cutting implements that remained in vogue for nearly 1.5 million years. As recently as 400,000 years ago, thrusting spears used during the hunt of large prey in what is now Germany were state of the art. But they could only be used up close, an obvious and sometimes dangerous limitation.

Even as they acquired the more modern anatomy seen in living humans, the ways our ancestors lived, and the tools they created, changed as well.

Humans took a leap in tool tech with the Middle Stone Age some 300,000 years ago by making those finely crafted tools with flaked points and attaching them to handles and spear shafts to greatly improve hunting prowess. Projectile points like those Potts and colleagues dated to 298,000 to 320,000 years old in southern Kenya were an innovation that suddenly made it possible to kill all manner of elusive or dangerous prey. “It ultimately changed how these earliest sapiens interacted with their ecosystems, and with other people,” says Potts.

Scrapers and awls, which could be used to work animal hides for clothing and to shave wood and other materials, appeared around this time. By at least 90,000 years ago barbed points made of bone—like those discovered at Katanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo—were used to spearfish

As with fossils, tool advancements appear in different places and times, suggesting that distinct groups of people evolved, and possibly later shared, these tool technologies. Those groups may include other humans who are not part of our own lineage.

Last year a collection including sophisticated stone blades was discovered near Chennai, India, and dated to at least 250,000 years ago. The presence of this toolkit in India so soon after modern humans appeared in Africa suggests that other species may have also invented them independently—or that some modern humans spread the technology by leaving Africa earlier than most current thinking suggests.

100,000 to 210,000 Years Ago: Fossils Show Homo sapiens Lived Outside of Africa

A skull found in Qafzeh, from the collection at the American Museum of Natural History Wapondaponda via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 3.0

Many genetic analyses tracing our roots back to Africa make it clear that Homo sapiens originated on that continent. But it appears that we had a tendency to wander from a much earlier era than scientists had previously suspected.

A jawbone found inside a collapsed cave on the slopes of Mount Carmel, Israel, reveals that modern humans dwelt there, alongside the Mediterranean, some 177,000 to 194,000 years ago. Not only are the jaw and teeth from Misliya Cave unambiguously similar to those seen in modern humans, they were found with sophisticated handaxes and flint tools.

Other finds in the region, including multiple individuals at Qafzeh, Israel, are dated later. They range from 100,000 to 130,000 years ago, suggesting a long presence for humans in the region. At Qafzeh, human remains were found with pieces of red ocher and ocher-stained tools in a site that has been interpreted as the oldest intentional human burial.

Among the limestone cave systems of southern China, more evidence has turned up from between 80,000 and 120,000 years ago. A 100,000-year-old jawbone, complete with a pair of teeth, from Zhirendong retains some archaic traits like a less prominent chin, but otherwise appears so modern that it may represent Homo sapiens. A cave at Daoxian yielded a surprising array of ancient teeth, barely distinguishable from our own, which suggest that Homo sapiens groups were already living very far from Africa from 80,000 to 120,000 years ago.

Even earlier migrations are possible; some believe evidence exists of humans reaching Europe as long as 210,000 years ago. While most early human finds spark some scholarly debate, few reach the level of the Apidima skull fragment, in southern Greece, which may be more than 200,000 years old and might possibly represent the earliest modern human fossil discovered outside of Africa. The site is steeped in controversy, however, with some scholars believing that the badly preserved remains look less those of our own species and more like Neanderthals, whose remains are found just a few feet away in the same cave. Others question the accuracy of the dating analysis undertaken at the site, which is tricky because the fossils have long since fallen out of the geological layers in which they were deposited.

While various groups of humans lived outside of Africa during this era, ultimately, they aren’t part of our own evolutionary story. Genetics can reveal which groups of people were our distant ancestors and which had descendants who eventually died out.

“Of course, there could be multiple out of Africa dispersals,” says Akey. “The question is whether they contributed ancestry to present day individuals and we can say pretty definitely now that they did not.”

50,000 to 60,000 Years Ago: Genes and Climate Reconstructions Show a Migration Out of Africa

A digital rendering of a satellite view of the Arabian Peninsula, where humans are believed to have migrated from Africa roughly 55,000 years ago Przemek Pietrak via Wikipedia under CC BY 3.0

All living non-Africans, from Europeans to Australia’s aboriginal people, can trace most of their ancestry to humans who were part of a landmark migration out of Africa beginning some 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, according to numerous genetic studies published in recent years. Reconstructions of climate suggest that lower sea levels created several advantageous periods for humans to leave Africa for the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East, including one about 55,000 years ago.

“Just by looking at DNA from present day individuals we’ve been able to infer a pretty good outline of human history,” Akey says. “A group dispersed out of Africa maybe 50 to 60 thousand years ago, and then that group traveled around the world and eventually made it to all habitable places of the world.”

While earlier African emigres to the Middle East or China may have interbred with some of the more archaic hominids still living at that time, their lineage appears to have faded out or been overwhelmed by the later migration.

15,000 to 40,000 Years Ago: Genetics and Fossils Show Homo sapiens Became the Only Surviving Human Species

A facial reconstruction of Homo floresiensis, a diminutive early human that may have lived until 50,000 years ago John Gurche

For most of our history on this planet, Homo sapiens have not been the only humans. We coexisted, and as our genes make clear frequently interbred with various hominin species, including some we haven’t yet identified. But they dropped off, one by one, leaving our own species to represent all humanity. On an evolutionary timescale, some of these species vanished only recently.

On the Indonesian island of Flores, fossils evidence a curious and diminutive early human species nicknamed “hobbit.” Homo floresiensis appear to have been living until perhaps 50,000 years ago, but what happened to them is a mystery. They don’t appear to have any close relation to modern humans including the Rampasasa pygmy group, which lives in the same region today.

Neanderthals once stretched across Eurasia from Portugal and the British Isles to Siberia. As Homo sapiens became more prevalent across these areas the Neanderthals faded in their turn, being generally consigned to history by some 40,000 years ago. Some evidence suggests that a few die-hards might have held on in enclaves, like Gibraltar, until perhaps 29,000 years ago. Even today traces of them remain because modern humans carry Neanderthal DNA in their genome.

Our more mysterious cousins, the Denisovans, left behind so few identifiable fossils that scientists aren’t exactly sure what they looked like, or if they might have been more than one species. A recent study of human genomes in Papua New Guinea suggests that humans may have lived with and interbred with Denisovans there as recently as 15,000 years ago, though the claims are controversial. Their genetic legacy is more certain. Many living Asian people inherited perhaps 3 to 5 percent of their DNA from the Denisovans.

Despite the bits of genetic ancestry they contributed to living people, all of our close relatives eventually died out, leaving Homo sapiens as the only human species. Their extinctions add one more intriguing, perhaps unanswerable question to the story of our evolution—why were we the only humans to survive?

Brian Handwerk is a science correspondent based in Amherst, New Hampshire.

Source https://scfh.ru/en/papers/where-has-homo-sapiens-come-from/

Source https://www.thoughtco.com/southern-dispersal-route-africa-172851

Source https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/essential-timeline-understanding-evolution-homo-sapiens-180976807/