Charles Darwin and His Voyage Aboard H. M. S. Beagle

Charles Darwin’s evolutionary revelation in Australia

Frank Nicholas received funding from a range of donors for the publication of “Charles Darwin in Australia” (Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1989, 2002, 2008), co-authored with Jan Nicholas. The donors are listed in the acknowledgements section of each edition of that book.

Partners

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

One hundred and eighty years ago today, on January 12, 1836, HMS Beagle entered Sydney Harbour with the 26-year old Charles Darwin on board. Sydney was just one of many ports of call for the Beagle on its five-year round-the-world surveying voyage.

Before departing the antipodes two months later, he was to have a revelation that would eventually inform his grand theory of evolution by natural selection. In addition to that, he would marvel at the many natural wonders – flora, fauna and geological – of the great southern land.

Across the mountains

During the Beagle’s 19 days in Sydney, Darwin “hired a man & two horses to take [him] to Bathurst…to get a general idea of the country”.

This and the following quotations are from Darwin’s Beagle diary or Beagle letters.

In the Blue Mountains, he traversed what is now called the Charles Darwin Walk, a wonderful bush track that follows Jamison Creek from Wilson Park to Wentworth Falls:

Following down a little valley & its tiny rill of water, suddenly & without any preparation, through the trees, which border the pathway, an immense gulf is seen at the depth of perhaps 1500 ft beneath ones feet.

Always questioning what he saw, Darwin immediately began speculating on how the magnificent Jamison Valley had been formed.

Near present-day Wallerawang, just west of the Blue Mountains, he examined a rat-kangaroo and a platypus. Noting that they occupied (what we now call) ecological niches similar to those of the rabbit and water rat in the northern hemisphere, he wondered in his diary why a single creator would make such different animals for the same apparent purpose: “Surely two distinct Creators must have been [at] work.”

This was the first (and not the last) time the young naturalist penned such thoughts.

In and around Sydney, Darwin and his servant Syms Covington collected at least 110 species of animals, including a mouse not previously described (originally Mus gouldii; later Pseudomys gouldii; unfortunately now extinct), a crab, a snake, frogs, lizards, shells (including an oyster, a mudwhelk, air breathers, a sand snail, and a trochid or top shell) and 97 insects, 42 of which had not previously been described.

Four of these were named (by other authors) after Darwin: a Leaf beetle Idiocephala darwini ; a Seed bug Ontiscus darwini; a Gasteruptiid wasp Foenus darwinii; and a Bee Halictus darwiniellus.

The remaining novel insects comprise six Leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae), four Stink bugs (Pentatomidae), a Seed bug (Lygaeidae), an Assassin bug (Reduviidae), a Water boatman (Corixidae), a Leafhopper (Cicadellidae), a Cicada (Cicadidae), a Flatid planthopper (Flatidae), a Froghopper or Spittlebug (Cercopidae), three Parasitic wasps (Chalcididae), an Encyrtid wasp (Encyrtidae), five Eucaratids (Eucharitidae), a Eulophid (Eulophidae), four Seed chalcids (Eurytomidae), five Lamprotatidae and one Torymid wasp (Torymidae).

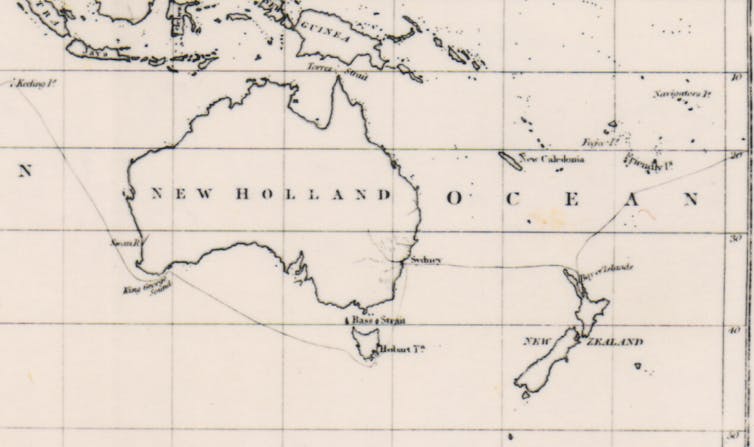

Darwin’s path around Australia on the Beagle. FitzRoy, R., Volume 2 of the official account of the voyage

Travelling south

On February 5, HMS Beagle arrived in Hobart. In the first few days, Darwin took “some long pleasant walks [on both sides of the Derwent River] examining the Geology of the country”. On February 11 he climbed Mt Wellington.

Three days were spent with Surveyor General George Frankland, who took Darwin on “two very pleasant rides” and with whom Darwin spent “the most agreeable evenings since leaving England”, presumably in Frankland’s house Secheron, which still exists in Battery Point.

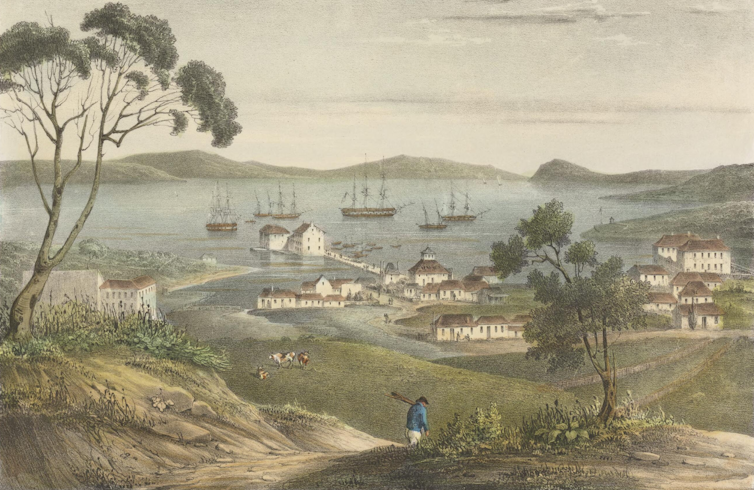

A lithograph of Hobart town in 1833, not long before Darwin’s arrival. St. Aulaire, A./National Library

It is not known whether Darwin told Frankland that one of those days (February 12) was his 27th birthday. If he did, it is most likely that Frankland would have incorporated a small celebration into the dinner at “Secheron” that evening.

During his visit, Darwin also “dined…at the Attorneys General, where, amongst a small party of his most intimate friends he got up an excellent concert of first rate Italian Music”. His host was Alfred Stephen and the house is Stephenville, which also still stands in Hobart.

In and around Hobart, Darwin and Covington discovered a species of skink not then described (Cyclodus casuarinae, later changed to Tiliqua casuarinae), and collected five other lizards, a snake (which he thought harmless, but which could easily have killed him), a “new” species of flatworm (Planaria tasmaniana) and at least 119 species of insects (63 of which were “new”).

On March 7, 1836, HMS Beagle arrived in King George Sound, its third and final Australian port of call. In the following eight days, Darwin witnessed a corroboree, geologised around Vancouver Peninsula and Bald Head, and visited Strawberry Hill Farm (then belonging to the Government Resident, Sir Richard Spencer).

In and around the settlement, Darwin and Covington collected a native bush rat (Rattus fuscipes, a “new” species), a frog, at least 10 species of fish (two of which were “new”; Longhead Flathead and Common Jack Mackerel), several shellfish and 66 species of insects (48 being “new”).

The Australian bush rat, a previously unknown species of rodent discovered by Darwin ‘amongst the bushes at King George Sound’, as illustrated in Zoology, Part II (Mammalia). Frank Nicholas, Charles Darwin in Australia, 2008, Author provided

Arguably, the most important scientific legacy of Darwin’s visit to Australia was the key question of creation raised at Wallerawang. Darwin saw that similar ecological niches in different parts of the world tend to be occupied by very different species, and these are related to other species that occur in that part of the world.

This was the most important of Australia’s contributions to the ideas that eventually emerged to great effect in Darwin’s seminal work On the Origin of Species.

Charles Darwin and His Voyage Aboard H.M.S. Beagle

The Young Naturalist Spent Five Years on a Royal Navy Research Ship

- Share

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/HMS-Beagle-3000-3x2gty-579e23883df78c32765450a0.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Robert J. McNamara is a history expert and former magazine journalist. He was Amazon.com’s first-ever history editor and has bylines in New York, the Chicago Tribune, and other national outlets.

Charles Darwin’s five-year voyage in the early 1830s on H.M.S. Beagle has become legendary, as insights gained by the bright young scientist on his trip to exotic places greatly influenced his masterwork, the book “On the Origin of Species.”

Darwin didn’t actually formulate his theory of evolution while sailing around the world aboard the Royal Navy ship. But the exotic plants and animals he encountered challenged his thinking and led him to consider scientific evidence in new ways.

After returning to England from his five years at sea, Darwin began writing a multi-volume book on what he had seen. His writings on the Beagle voyage concluded in 1843, a full decade and a half before the publication of “On the Origin of Species.”

The History of H.M.S. Beagle

H.M.S. Beagle is remembered today because of its association with Charles Darwin, but it had sailed on a lengthy scientific mission several years before Darwin came into the picture. The Beagle, a warship carrying ten cannons, sailed in 1826 to explore the coastline of South America. The ship had an unfortunate episode when its captain sank into a depression, perhaps caused by the isolation of the voyage, and committed suicide.

Gentleman Passenger

Lieutenant Robert FitzRoy assumed command of the Beagle, continued the voyage and returned the ship safely to England in 1830. FitzRoy was promoted to Captain and named to command the ship on a second voyage, which was to circumnavigate the globe while conducting explorations along the South American coastline and across the South Pacific.

FitzRoy came up with the idea of bringing along someone with a scientific background who could explore and record observations. Part of FitzRoy’s plan was that an educated civilian, referred to as a “gentleman passenger,” would be good company aboard ship and would help him avoid the loneliness that seemed to have doomed his predecessor.

Darwin Invited to Join the Voyage in 1831

Inquiries were made among professors at British universities, and a former professor of Darwin’s proposed him for the position aboard the Beagle.

After taking his final exams at Cambridge in 1831, Darwin spent a few weeks on a geological expedition to Wales. He had intended to return to Cambridge that fall for theological training, but a letter from a professor, John Steven Henslow, inviting him to join the Beagle, changed everything.

Darwin was excited to join the ship, but his father was against the idea, thinking it foolhardy. Other relatives convinced Darwin’s father otherwise, and during the fall of 1831, the 22-year-old Darwin made preparations to depart England for five years.

Departs England on December 27, 1831

With its eager passenger aboard, the Beagle left England on December 27, 1831. The ship reached the Canary Islands in early January and continued onward to South America, which was reached by the end of February 1832.

South America From February 1832

During the explorations of South America, Darwin was able to spend considerable time on land, sometimes arranging for the ship to drop him off and pick him up at the end of an overland trip. He kept notebooks to record his observations, and during quiet times on board the Beagle, he would transcribe his notes into a journal.

In the summer of 1833, Darwin went inland with gauchos in Argentina. During his treks in South America, Darwin dug for bones and fossils and was also exposed to the horrors of enslavement and other human rights abuses.

The Galapagos Islands, September 1835

After considerable explorations in South America, the Beagle reached the Galapagos Islands in September 1835. Darwin was fascinated by such oddities as volcanic rocks and giant tortoises. He later wrote about approaching tortoises, which would retreat into their shells. The young scientist would then climb on top, and attempt to ride the large reptile when it began moving again. He recalled that it was difficult to keep his balance.

While in the Galapagos Darwin collected samples of mockingbirds, and later observed that the birds were somewhat different on each island. This made him think that the birds had a common ancestor, but had followed varying evolutionary paths once they had become separated.

Circumnavigating the Globe

The Beagle left the Galapagos and arrived at Tahiti in November 1835, and then sailed onward to reach New Zealand in late December. In January 1836 the Beagle arrived in Australia, where Darwin was favorably impressed by the young city of Sydney.

After exploring coral reefs, the Beagle continued on its way, reaching the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa at the end of May 1836. Sailing back into the Atlantic Ocean, the Beagle, in July, reached St. Helena, the remote island where Napoleon Bonaparte had died in exile following his defeat at Waterloo. The Beagle also reached a British outpost on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic, where Darwin received some very welcome letters from his sister in England.

Back Home October 2, 1836

The Beagle then sailed back to the coast of South America before returning to England, arriving at Falmouth on October 2, 1836. The entire voyage had taken nearly five years.

Organizing Specimens and Writing

After landing in England, Darwin took a coach to meet his family, staying at his father’s house for a few weeks. But he was soon active, seeking advice from scientists on how to organize specimens, which included fossils and stuffed birds, he had brought home with him.

In the following few years, he wrote extensively about his experiences. A lavish five-volume set, “The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle,” was published from 1839 to 1843.

And in 1839 Darwin published a classic book under its original title, “Journal of Researches.” The book was later republished as “The Voyage of the Beagle,” and remains in print to this day. The book is a lively and charming account of Darwin’s travels, written with intelligence and occasional flashes of humor.

The Theory of Evolution

Darwin had been exposed to some thinking about evolution before embarking aboard H.M.S. Beagle. So a popular conception that Darwin’s voyage gave him the idea of evolution is not accurate.

Yet is it true that the years of travel and research focused Darwin’s mind and sharpened his powers of observation. It can be argued that his trip on the Beagle gave him invaluable training, and the experience prepared him for the scientific inquiry that led to the publication of “On the Origin of Species” in 1859.

On this day: Charles Darwin departs Australia

Darwin sailed away in 1836 with 10,000 scribbled words on the Australian wilderness, which helped build his theory on evolution.

ON 14 MARCH 1836, Charles Darwin – the father of modern biology – sailed away from Australia on the HMS Beagle.

Upon departing, he wrote: “Farewell, Australia! You are a rising infant and doubtless someday will reign a great princess in the South: but you are too great and ambitious for affection, yet not great enough for respect. I leave your shores without sorrow or regret.”

Aged just 27, Darwin was yet to realise that in his journal were observations on landscapes and wildlife that would shape key ideas in his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Just five years earlier, he had begun his life of adventure. Too squeamish to finish medical school and not ready for his second career choice as a clergyman, a young Darwin found himself attached to a geological expedition to Wales.

Upon his return from that to London in August 1831, he learned that he had been recommended to accompany Captain Robert FitzRoy on a two-year surveying expedition to South America. This later became a five-year journey around the world aboard the HMS Beagle.

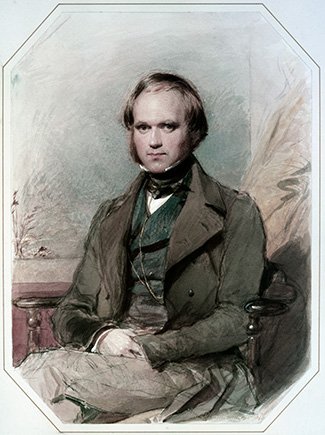

Charles Darwin, painted by George Richmond in the late 1830s. CREDIT: George Richmond

Darwin and the Beagle in Australia

Captain FitzRoy wasn’t in search of an expert, but he needed a learned companion, as well as someone to collect specimens and record details of the journey. While Charles was not a formally trained scientist, his charisma and enthusiasm for natural history were credentials enough to get him aboard. Upon accepting the invitation, Charles wrote to Captain FitzRoy, “My second life will begin and it shall be as a birthday for the rest of my life.”

The voyage embarked on 27 December 1831 from Plymouth, England. After surveying the coast of South America, sailing west to the Galapagos Islands, then moving on to Tahiti and New Zealand, it arrived in Australia. The journey so far had already taken more than four years.

The Beagle arrived and anchored in Sydney Cove on 12 January 1836. Darwin was keen to explore the nascent city (population of 23,000) and was impressed by its progress compared to what he had observed in South America.

Despite his appreciation of Sydney’s built environment, Charles was initially underwhelmed by the landscape and vegetation, deeming it dry and uninteresting. “The nearly level country is covered with thin scrubby trees, bespeaking the curse of sterility,” he noted.

Charles Darwin’s thoughts on Australian wildlife

His tune began to change, however, when given the opportunity to indulge in geology, one of his great loves. On 16 January, Darwin set out on horseback to the Blue Mountains, which he speculated had been created by erosion but couldn’t believe. It wasn’t until years later, when he came to accept that the geological history of the world was far older than previously appreciated, that he came back to his notes and realised his assumptions had been right.

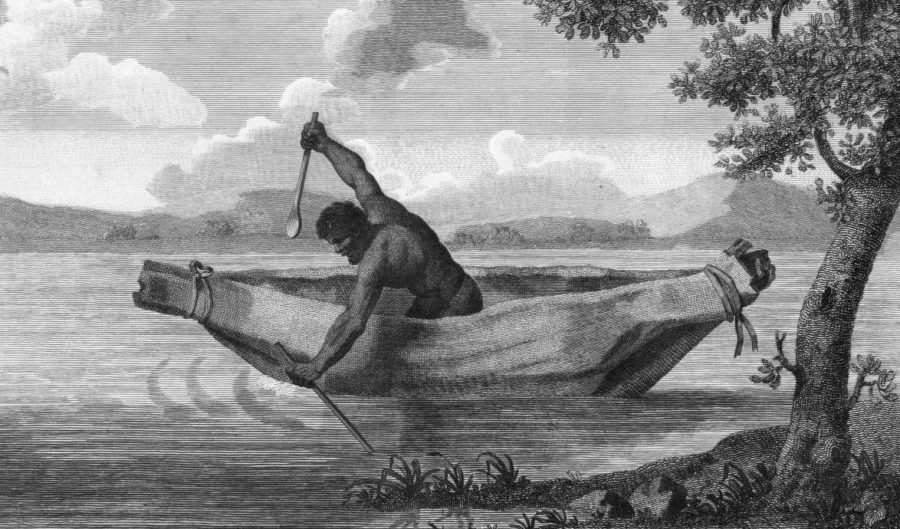

Three days later, Darwin encountered a platypus on the bank of the Coxs River at Wallerawang. Noting similarities between the platypus and the European water-rat, he was intrigued by shared features and behaviour. Later he would notice similarities between the marsupial potoroo and the European rabbit, shaping his thoughts on how animals adapt to the demands of the environment.

These observations and speculations were Darwin’s “most important scientific thoughts in Australia,” says Professor Frank Nicholas, an expert on Darwin at the University of Sydney. “He noticed that animals in the Southern Hemisphere were adaptively similar to animals of different species in the Northern Hemisphere. He questioned why two animals of a very different physical design would be ‘created’ to serve the same purpose within an ecological niche.”

This observation would later support Darwin’s theory of natural selection, detailed many years later in On the Origin of Species, published in 1859.

Observations of the platypus led Darwin to develop his theory about the adaptation of species to the environment. CREDIT: John Lewin (1808)

The Beagle in Tasmania

The Beagle sailed on to Hobart, Tasmania, arriving on 5 February. Here, Darwin admired the native vegetation and enjoyed a trek up Mount Wellington, writing:

“In many parts the Gum grew to a great size, and composed a noble forest. In some of the dampest ravines, tree-ferns flourished in an extraordinary manner…the foliage forming the most elegant parasols.”

His notes on Tasmanian wildlife contributed to the idea that species found on adjoining, yet separate landmasses will share similar traits, having arisen from the same ancestor (the theory of biogeography).

“Britain is separated by a shallow channel from Europe, and the mammals are the same on both sides,” Darwin wrote. “And so it is with all the islands near the shores of Australia.”

The Beagle then sailed to Albany, Western Australia on 6 March. In the area surrounding King George Sound, Darwin collected shells, barnacles and 48 species of insect new to science.

When he finally departed Australia from Albany on 14 March, Darwin was bound for the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. Here he developed a theory on the formation of coral atolls (that they form as corals grow upwards atop a subsiding volcanic island), which persists today.

Darwin never returned to Australia, though he remained in close contact with collectors such as Syms Covington, the cabin boy aboard the Beagle, who migrated to Australia in 1838. Covington sent Darwin a collection of barnacles, and correspondence with him continued to inform Darwin’s developing theories.

Read Next

On this day: Pemulwuy is killed

Remembering the Indigenous resistance fighter determined to maintain Aboriginal traditions by resisting British rule.

On this day: Trout arrive in Australia

On 4 May 1864, the first brown trout eggs ever successfully shipped to Australia hatched in the cool waters of Plenty River, Tasmania – causing a ripple effect for both fishing and conservation that endures to this day.

The evolution of Anzac Day from 1915 until today

Australians have commemorated Anzac Day on 25 April for more than a century, but the ceremonies and their meanings have changed significantly since 1915.

Source https://theconversation.com/charles-darwins-evolutionary-revelation-in-australia-52282

Source https://www.thoughtco.com/charles-darwin-and-his-voyage-1773836

Source https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/blogs/on-this-day/2014/03/on-this-day-charles-darwin-departs-australia/