William Bartram

F rom 1773-77, William Bartram (1739-1823) explored the American Southeast to record the region’s plants, animals, and Indian peoples. Published in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1779 Bartram’s Travels has become a classic, in large part because of Bartram’s descriptions of Florida.

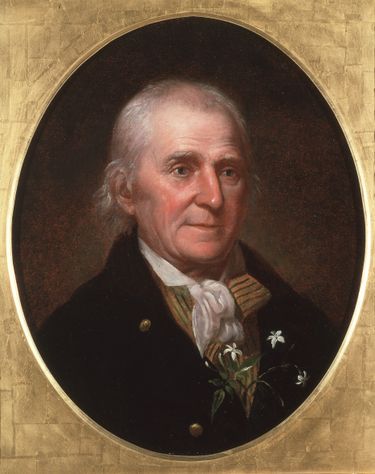

Portrait of William Bartram by Charles Willson Peale via Wikimedia Commons

In the spring of 1774, William Bartram, a naturalist from Kingsessing, Pennsylvania, traveled inland from the St. Johns River to the Alachua Savanna, present-day Paynes Prairie Preserve. In 1772, Dr. John Fothergill had commissioned Bartram to collect the natural history specimens in the Georgia colony for the sum of £150 per annum. Having failed in 1766 to establish a plantation outside near present-day Jacksonville, Florida, Bartram had not yet made a place for himself in life. Now, at the age of thirty-five, he returned to East Florida to follow his favorite pursuit, the study of plants and animals.

In Bartram’s eyes, spring-fed streams, sandy banks, and ancient trees formed a natural paradise. At the village of Cuscowilla, near the present-day town of Micanopy, Bartram was greeted by the Creek mico, or chief, Cowkeeper in the spring of 1774. Cowkeeper’s people were hunters and farmers, and Bartram noted the numbers of Spanish cattle and horses in the Alachua Savanna. He believed their herds rivaled those of prosperous Pennsylvania farms of his youth.

Bartram, of Quaker upbringing, had arrived in Florida as a peace-loving British subject. Three years later, he returned to Philadelphia as a citizen of an emerging nation, the United States of America. While he traveled his 2400-mile trip, the thirteen British colonies began the War of Independence.

A Naturalist’s Vision

In East Florida, the fields seemed painted with the colors of wildflowers, and Bartram drew many species: the flowering paw paw, pink bindweed, Magnolia grandiflora, and lovely American lotus. Indeed, few things escaped the notice of Bartram’s sharp eye. The fragile celestial lily that he described near Lake Dexter was not found again for the next 150 years! Nature’s variety inspired Bartram, and his drawings and records introduced readers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean to East Florida. Bartram also described the region’s fauna – the black vulture, gopher tortoise, and sandhill crane, performing its distinctive mating dance.

Although he wrote about the alligator as a noisy dragon-like animal with a “horrifying roar,” biologists at the University of Florida, Gainesville, have confirmed Bartram’s observations of group feeding and maternal care among alligators. With time, Bartram’s memories of Florida were reshaped by national ideals.

Like many visitors to Florida, Bartram enjoyed fish stories. At Lake George, he observed water so clear that all fish, big and small, seemed to have an equal chance to survive. “Here,” he said, “the trout swims by the very nose of the alligator and laughs in his face, and the bream swims by the trout.” Bartram made scientific drawings of these fish, but this spring was his excuse to describe nature in the terms of a democratic society.

Bartram also observed the native peoples of Florida, and his book included his portrait of a Seminole chief, Long Warrior. As Congress debated the constitutional war powers of the president, Bartram urged his readers and the federal government to avoid warfare with Indian peoples. Specifically, he suggested sending diplomats to learn Indian customs and languages. Unfortunately, Bartram’s sensible advice was ignored, and three Seminole Wars characterized nineteenth-century Florida.

Bartram’s book, better read in Europe than in his own country, was translated into almost every major European language. The best remembered sections described Florida. British poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge used Bartram’s imagery. Indeed, the Romantic Movement owed much to sights, sounds, and fragrances which Bartram described in Florida.

Bartram’s writings also popularized Florida for settlement. In the 1830s, the famous bird painter, John James Audubon, attributed a premature land boom to Bartram’s “flowery sayings.” In 1873, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, promoted the region’s natural history in Palmetto-Leaves, a collection of letters for women. “We never pretended that Florida was the Kingdom of Heaven,” Mrs. Stowe wrote from Mandarin, but “it is a child’s Eden.”

Bartram’s Florida received national literary attention again in 1942 after prize-winning author of The Yearling, Marjorie Kinan Rawlings, published Cross Creek and Cross Creek Cookery. Like Bartram, Rawlings was a keen observer: “There is no such thing,” she wrote, “as an ugly tree, but the Magnolia grandiflora has a unique perfection.”

Modern travelers are lucky. The State of Florida has used Bartram’s writings and drawings to restore the Alachua Savanna as Paynes Prairie State Preserve for public recreation and edification.

Historical Background: British Period, 1763-1783

The Florida of Bartram’s day was larger than the present state. In fact, there were two Floridas, East Florida and West Florida. In 1763, the Treaty of Paris concluded the long struggle between Great Britain, France, and Spain for control of North America. France ceded land east of the Mississippi River (excluding New Orleans) to Great Britain, and western Louisiana to Spain. Spain, in turn, gave up La Florida to Britain in exchange for Cuba, “the Pearl of the Antilles.” Spanish La Florida thus became the fourteenth and fifteenth British colonies in North America.

This treaty arrangement eliminated Spanish foothold on the eastern Atlantic coast. The old Spanish fort city of St. Augustine served as capital of East Florida. The seat of government for British West Florida was Pensacola, the best deep narrow harbor on the gulf coast. Many of Pensacola’s French residents transferred their allegiance to the British king.

Great Britain now held jurisdiction over lands to the Mississippi River and tried to solidify control and establish policies. The Royal Proclamation Act of 1763 reserved the region north of the 31st parallel and west of the Appalachian Mountains for Indian groups. The Board of Trade in London, however, soon realized that there were white settlers in this restricted fertile zone and agreed to raise the northern boundary of West Florida. This decision did not satisfy other colonists who expected land in return for their loyalty to the crown and contributed to the deterioration of relations between the colonies and the mother country prior to the Revolutionary War.

At this time, John Bartram, William’s father, hoped for appointment as Royal Botanist to King George III, and in 1765, he and his son explored a section of East Florida “for the benefit of the new colony.” In a published report, John Bartram recorded soil types, and other natural history information for would-be landholders of plantations.

Despite the attempted gentrification of East Florida through the British plantation system, the region to which William returned in 1774 was a dangerous place. Armed American patriots from Georgia were making troublesome border raids. Increasingly hostile Creeks and Seminoles outnumbered whites and restricted travel across their lands.

To the west, the powerful Muscogulges, a Creek alliance of diverse Indian peoples, controlled a large area from eastern Georgia and north Florida to central Alabama; sometimes they farmed sites occupied by earlier Florida Indian groups, decimated by disease, enslavement, and relocation. Commercial Creek hunters procured deerskins and other pelts for British outfits in a regulated trade.

At the time of Bartram’s visit, Seminoles affiliated with Hitchiti-speaking Creeks in north central Florida. Inhabiting villages in the Gainesville and Tallahassee regions, as well as the panhandle, they hunted as far south as present-day Tampa.

Staples were melons, beans, squash and corn. Although Bartram carried a supply of dried meat and cheese with him, he described with foods offered him:

- conte jelly made from smilax

- live oak acorns

- rice (obtained by trade) boiled with raccoon, fowl, or fish

- “good” corn-flour hot cakes fried in bear oil

- trout stewed with oranges

- cooked plums in hone

- cornmeal mixed with the “milk” of hickory nuts)

- strawberries, fox grapes, crabapples, persimmons

- a refreshing Creek beverage of honey and water)

- shellfish

- beef parts

Conte

In his Travels, Bartram described “conte,” a Creek food prepared from smilax root: “a small quantity of this mixed with warm water and sweetened with honey, when cool becomes a beautiful, delicious jelly, very nourishing and wholesome.” Today, Seminole cooks make conte from zamia, a different plant. Smilax is a common native vine, greenbriar, but honey was a trade item. At the time of his travels, Bartram ascertained that European introduced honeybees had not yet spread to West Florida.

Book of Travels

Published in 1791, Bartram’s Travels is a book of four different parts. Part one outlines preparations for his trip and describes his journey in 1773 from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to the Georgia colony. Part two recounts to Bartram’s travels in British East Florida in the year 1774. Part three describes his investigations in the territories of the Cherokees and Choctaws, or West Florida, Alabama, and the region west to the Mississippi River in 1775. Part four contains Bartram’s valuable accounts of Southeastern Indian groups at the time of the American Revolution.

Besides the Creeks and Seminoles, Bartram discussed three other Indian groups living between the Savannah and Mississippi rivers: (1) Cherokees occupying in the mountain valleys of the Carolinas, Tennessee and Georgia, (2) Choctaws controlling lands from the Tombighee to Mississippi rivers, and (3) Chickasaws to the north of the Choctaws.

Bartram in Florida

Arrival in East Florida, 1774

In March 1774, William Bartram sailed from St. Simons Island, Georgia, to the St. Johns River. His host on St. Simons Island was James Spalding, senior partner in the firm of Spalding and Kelsell, which traded goods with the Creeks. Spalding, an in-law of Bartram’s traveling companion, John McIntosh, gave Bartram letters to his agents instructing them to furnish guides, horses and other assistance.

Bound for Spalding’s Lower Store on the St. Johns River, Bartram forwarded his trunk with Spalding’s traders. The Lower Store, managed by Charles McLatchie served as a distribution point for the Upper Store, under the direction of Job Wiggens and his Indian wife, and inland trading houses at Alachua and Talahasochte.

Amelia Island

As the vessel on which Bartram and McIntosh had passage rounded Cumberland Island, it met a trading schooner returning from stores on the Sr. Johns River. Passengers told of recent Indian raids, and Bartram’s vessel turned back. Bartram prevailed upon the captain to put him and McIntosh ashore on Cumberland Island, uninhabited except for Fort William. After “harsh treatment from thorny thickets and prickly vines,” the two men proceeded by boat to Amelia Island.

Fernandina Beach

Bartram and his companion landed on the north end of Amelia Island and crossed Egan’s Creek (now Clark’s Creek) to Lord Egmont’s plantation, an estate of 8000-9000 acres with a town laid out in 1770. They remained for several days with Mr. Egan, the agent or manager. Having failed as a planter, Bartram was impressed with the indigo growing in the northeastern sector, present-day Fernandina Beach. He also observed four large mounds called the “Ogeeche mounts,” remnants of one still evident in 1940 on the grounds of Public School #1 on the north side of Atlantic Avenue near 12th Street.

Cowford Ferry

Bartram and a party left the Egmont plantation by boat via Kingsley Creek and across Nassau Sound and probably camped on the north end of Talbot Island. Bartram reported orange trees “in full bloom” and air filled with “fragrance.” Before proceeding by way of Sawpit and Sister creeks to the public ferry in Cowford, Bartram procured a small boat and fitted it with sails for his journey up the St. Johns River. He and McIntosh parted company. Bartram probably made his first camp in or near Ortega.

The next day, he re-crossed the river and visited the Marshall plantation known to him from earlier travels with his father. Abraham Marshall, a slave owner, presented Bartram with a sample of fine indigo blue dye “of his own manufacture.” At the next plantation, a hospitable host assured him that the Indian trouble was over and to proceed without fear.

Up the St. Johns River to Palatka

Bartram continued south and landed at the old Spanish fort at Picolata. In 1765, he and his father had attended the congress held there by Governor James Grant and Creek representatives. Traveling up river, Bartram was impressed by “incredible numbers of small flying insects” a number “greater than the whole race of mankind.” He camped near the mouth of Clark’s Creek, Clay Co. Recording large “floating islands” of water lettuce and “majestic” cypress trees, Bartram followed the western shore of the St. Johns River. This part of Bartram’s account inspired French writer Rene’ de Chateaubriand to write of “floating islands” and “young crocodiles” taking “passage on these floral vessels” in Atala, a popular novella published 1801.

After “doubling a long point of land” (Forrester’s Point), Bartram proceeded to a Creek village near Palatka. Youths were fishing and shooting frogs with bows and arrows, as women hoed corn. Bartram admired the llarge, carefully tended orange grove and “several hundred acres cleared” for corn, beans, “batatas” (potatoes), “pompions” (pumpkins), squashes, melons, and tobacco. By 1875, Palatka was a resort for consumptives and terminus of the steamer line from Charleston, South Carolina.

The Lower Store

Between present-day East Palatka and San Mateo, Bartram stopped at Carlotia, an experimental community founded by Denys Rolle in 1764 with British vagrants, debtors and social outcasts. Ten years later, only the overseer, blacksmith, and their families remained. Bartram described the “beautiful shrub” paw paw at this site, now the Rollestown location of a Florida Power and Light generating plant. Having secured directions to Murphy’s Island where the trading party had secured goods and his gear, Bartram continued up river to the Lower Store at or near present-day Stokes Landing.

The Alachua Savanna

In April, Bartram and a party set out for an inland trading house near Lochloosa Creek (at the northwestern corner of Orange Lake) and the River Styx. The Creeks, Bartram learned, had recently moved from their village at the edge of the great Alachua Savanna to Lake Tuscawilla (near present-day Micanopy), because of the “stench of putrid fish and reptiles.” Again, the French writer Rene’ de Chateaubriand borrowed this town from Bartram’s Travels for the Seminole “capital” in Atala, a story of ill-fated Indian love.

Return to the Lower Store

The traders continued on to the trading store near Chacala Pond, while Puc Puggy the Flower Hunter, as the Creek mico Cowkeeper called Bartram, explored the beautiful Alachua Savanna. In early May, he rejoined the trading party on their return to the Lower Store. They probably crossed the old Spanish Highway about 1.5 miles south of Prairie Creek and continued northwest to Rochelle. Following the path to Lochloosa Creek, the party camped at Cowpen Lake and returned the next day to the Lower Store.

Lake George

In mid May, traders went ahead with goods to the Upper Store at present-day Astor. Bartram followed in his small boat, passing Mount Hope, a large shell mound “named by my father” and now demolished for road-fill. Bartram mentioned that the British residents had converted older Spanish orange groves into a large indigo plantation. At Mount Royal (Fruitland Cove), the party spent a night with a former “Indian trader,” Mr. Kean. On Lake George, they camped at the south end of Drayton’s Island near remains of a large mound and “grand avenue.” Crossing Lake George (15 miles wide), they spent one night at Cedar Point (Zinder Point), where the lake joins the St. John’s River. Here Bartram described lantana, an orange hibiscus, and bears. The following day, they reached the Upper Store. Bartram remained only a few days.

Lake Dexter

En route to a plantation 60 miles up river, Bartram was accompanied by a Mustee youth who soon tired of his labors and quit. Bartram’s first camp was near Manhattan, some 3 miles from the Upper Store on the west side of the Sr. Johns River. He crossed Lake Dexter and camped at a shell mound. Fishing for his supper, he encountered the alligators so vividly described as “crocodiles” in Chapter V of his Travels: “two very large ones attacked me closely, at the same instant, rushing up with their heads and part of their bodies above the water, roaring terribly and belching floods of water over me. They struck their jaws together so close to my ears, as almost to stun me.” Bartram spent two or three days exploring this rich natural area and observed the snake bird, anhinga.

Yamassee Burial Ground (St Francis)

Setting up camp in the dark on the second night, Bartram found that he had “unwittingly taken up my lodging on the borders of an ancient burying ground; sepulchres or tumuli of the Yamassees, who were here slain by the Creeks in the last decisive battle.” In attendance at the Creek town of Cuscowilla, Bartram had earlier observed Yamassees who spoke Spanish.

New Smyrna

Having weathered a violent early June storm, Bartram reached the plantation owned by Lord Beresford, about 30 miles from the Minorcan colony of New Smyrna founded in 1767. For more than a century, this region, with particularly rich soil, produced large quantities of sugar and syrup, in addition to esteemed Indian River citrus. Tourists today can enjoy Sugar Mill Gardens at Daytona Beach and the New Smyrna Sugar Mill Historical Memorial at New Smyrna Beach.

Blue Springs

Mr. Bernard, the manager of the Beresford Plantation, took Bartram to Blue Springs, visited with his father John Bartram on 4 January 1766. “This tepid water,” Bartram reported, “has a most disagreeable taste, brassy and vitriolic, and very offensive to the smell, much like bilge water or the washings of a gun barrel.” The largest spring in the St. Johns River Basin, Blue Springs, the southernmost point of his journey, is now a state park and manatee sanctuary in Volusia County.

Arrival at the Upper Store

Returning to the Upper Store via St. Francis, Spring Garden Creek, and Orange Bluff (Bluffton), Bartram observed many birds-the sandhill crane, limpkin, curlew, and wood stork. Bartram stopped and spent another night on the eastern bank of the St. Johns River to prepare his natural history collections before arrival at the Upper Store. There he bid “adieu” to Job Wiggens and set out again for the Lower Store.

Second Trip to the Lower Store

Bartram camped again at Cedar Point and touched on a small island he called “The Isle of Palms.” Two miles south of Silver Glen Springs (Bartram’s Johnson Springs), a beautiful spot in the Ocala National Forest, wolves made off with fish hanging over Bartram’s sleeping head. Bartram followed the run of Salt Springs (Bartram’s Six Mile Springs) to its source and continued northwest to Rocky Point of Lake George. He and again visited Mr. Kean at Mount Royal and reached the Lower Store in early June 1774.

Return to the Alachua Savanna

In mid June, Bartram set out for the “Little St. Juan” (Suwannee River). The first day’s journey took the party about 25 miles to Cowpen Lake. Bartram recorded the Creek’s use of garfish teeth to tip their arrows and provided the first scientific description of the gopher tortoise. Near Cuscowilla, the party divided. Cowkeeper’s people greeted Bartram’s group and offered them the “thin drink” of casual hospitality.

Lake Kanapaha

Live oaks that Bartram described still stand at Lake Kanapaha, and a trail marker notes his charming campsite at Kanapaha Botanical Gardens. En route, the party observed wolves, small black color variants of the southern red wold, feeding on the carcass of a horse. Archer Road (S.R. 24) approximates the old trail, and the landscape of little lakes and sinkholes which Bartram noted en route to present-day Bronson, Levy Co., are characteristic of the limestone (karst) typology.

Manatee Springs

Having camped near the Big or Little Waccasassa River, Bartram’s group traveled to Long Pond, 2 miles south of Chiefland. Their destination, the store at Talahasochte, has been identified with Ross Landing, a bluff 6 miles upstream from Manatee Springs, today a state park. There, Bartram described the “boil” of the spring and accurately recorded eruptions every 34 seconds. Bartram observed manatee bones along the banks. Today, the manatee, Florida’s official marine mammal, is an endangered species.

Suwannee River

Bartram described the Suwannee River as the most beautiful river he had ever seen. His excursion apparently followed a trading path for 1.5 miles. Turning west to California Creek headwaters, he proceeded north 8 or 9 miles towards present-day Oldtown, before returning to Talahasochte. After completing their business with the coordial Creek mico, White King, who gave Bartram permission to collect in lands under his control. Although Bartram did not explore as far south as the true Florida scrub, in the company of a guide, he noted the “clamorous” Florida scrub jay, now an endangered species.

Return to the Lower Store

The trade party returned to the Lower Store by way of Cowpen Lake. Late in July 1774, Bartram made one last “little voyage” to a favorite spot, Salt Springs, today a popular recreation site. On his return to the Lower Store, he found a very large party of Creeks encamped in the grove. Led by Long Warrior, whose portrait Bartram later published in the Travels, these rowdy warriors were setting out to fight their traditional enemies, the Choctaws. Angry that the store manager Charles McClatchie denied their leader credit, some young braves frightened Bartram with a truth test involving a rattlesnake, an animal taboo for them to kill. After their departure, McClatchie soothed Bartram’s shaken nerves with an invitation to a watermelon festival at a Creek village nearby.

Departure from East Florida

Having enjoyed the festival, Bartram returned to the Lower Store as a trading schooner was preparing to leave for St. Simons Island, Georgia. Before the vessel sailed, Bartram crossed the St. Johns River with a party turning out the horses to range on the western bank. Bartram’s Travels refers to his departure in September, but other sources indicate early November 1774.

Pensacola, 1775

While waiting for a ship to take him west from Mobile, Alabama to the Pearl River in 1775, Bartram decided to embark for the Perdido River “for the purpose of securing the remains of a wreck.” Although his subsequent arrival in Pensacola was “merely accidental and undesigned,” the naturalist was soon introduced to Governor Peter Chester of West Florida who “commended my pursuits, and invited me to continue in West Florida in researches after subjects of natural history.” Chester offered to pay Bartram’s expenses and put him up with his own family. Already committed to collect specimens for the British Quaker physician, Dr. John Fothergill, Bartram declined the governor’s offer to survey West Florida. Although his visit to Pensacola was brief (less than 24 hours), he gave detailed descriptions of the city in his Travels.

During the next century, there was talk of ceding the sparsely settled Florida panhandle to Alabama. In 1875, poet and composer Sidney Lanier similarly praised the beauty of the gulf coastal bays and “fine fish and oysters” in his tourist guide, Florida: Its Scenery, Climate and History.

Return to Mobile

Anxious to continue his trip to the Mississippi River, Bartram returned by boat to Mobile. He was beginning to feel the effects of lingering fevers.

Spring and Summer, 1776

Bartram’s Travels does not give derails for the spring and summer of 1776, and his field journals from this period have been lost. While other colonists were consumed by the events of the American Revolution, Bartram revisited “several districts” of “the East borders of Florida.” Although a Quaker by background and a pacifist, at this time he joined a revolutionary force in Georgia for the purpose of repelling a rumored British invasion that never materialized.

Kingsessing, Pennsylvania, 1777

Bartram returned to Kingsessing, a community outside Philadelphia, in January of 1777. Shortly before his father’s death that year, the Battle of Brandywine occurred dangerously near the family property along the Schuykill River. The John Bartram Society has opened the house and gardens to the public. Following the War of Independence, William Bartram and his brother John Jr. developed their father’s garden into a successful nursery business. A sales catalog for 1783 lists many Florida trees and shrubs including live oak, magnolia, Andromeda (illustrated here by William Bartram), azalea, and for some reason, poison oak. William passed the rest of his long life in Kingsessing. He worked with students and colleagues and continued to publish. His records and drawings became part of a second book, Elements of Botany, in 1803, the first botanical textbook published in the United States by Benjamin Smith Barton.

Kings Essing Garden

On hearing the news of Bartram’s death in 1823, Thomas Jefferson wrote Bartram’s grieving niece: “he is not gone, he remains everywhere around you. When you wish to find him, you bate only to look in his garden, and in his work, and in his green world.”

Influences

One the new nation’s Founding Fathers, William Bartram’s high school teacher, Charles Thomson, was a classical scholar and the second man to sign the Declaration of Independence. In 1783, Thomson and another friend of Bartram’s, the botanist William Barton, selected the motto and image for the Great Seal of the United States. The Great Seal appears on dollar bills. Bartram’s finest student, Alexander Wilson, published the nation’s first bird book, a magnificent multi-volume undertaking with fine illustrations. Wilson, a fine popular poet, celebrated his friendship with Bartram in several of his published poems. Titian Ramsay Peale, a young admirer of both Bartram and Wilson, used the national bird, the bald eagle, in his designs for American coins.

Bartram as Naturalist

William Bartram discovered the oak-leaved hydrangea, a species new to science in southern Georgia. In the Southeast, William Bartram identified at least 358 plants, 150 of which were new to him. In Chapter V of his Travels, Bartram referred to his herbarium or collection of dried plant specimens as a “Hortus Siccus,” Latin for dry garden: “Having completed my Hortus Siccus, and made up my collections of seeds and growing roots, the fruits of my late western tour and sent them to Charleston, to be forwarded to Europe, I spent the remaining part of this season in botanical excursions.”

Traveling with specimens was not easy. Bartram sewed dried plant specimens into linen books transported by pack animal. He described laying out the books to dry after a mishap. Bartram was not able to preserve animal specimens, some of which, drawn and described, joined the soup pot.

Forty common species Bartram observed in Florida are:

- water lotus

- live oak

- magnolia sweet

- paw paw

- Spanish needle

- opuntia

- water lettuce

- pickerel weed

- timber rattlesnake

- diamondback rattlesnake

- pigmy rattlesnake

- water moccasin

- cottonmouth

- coachwhip snake

- corn snake

- brown water snake

- green snake

- scarlet snake

- Florida duck

- brown pelican

- sandhill crane

- anhinga

- snowy egret

- great blue heron

- black vulture

- red-shouldered hawk

- little green heron

- yellow-shafted flicker

- sunfish

- yellow bream gar

- bigmouth bass

- golden shiner

- leopard frog

- glass lizard

- alligator

- soft-shelled turtle

- gopher tortoise

The link below tells the story of the magnificent summer-flowering tree and John Bartram’s discovery of it in 1765 in Georgia. Named after Benjamin Franklin, the Franklinia is today extinct in the wild and reputedly all of today’s specimens across America and Europe derive from the seedlings that Bartram’s son William grew in their nursery just outside Philadelphia.

Literary Influence

Six European editions in different languages followed the first edition of Bartram’s Travels in 1791. These translations established Bartram’s reputation at no monetary benefit to him. European readers were particularly fascinated by his picturesque descriptions of sub-tropical America and its native Indians. Bartram’s book is still in print on both sides of the Atlantic.

The English poet, William Wordsworth read Bartram’s Travels as he traveled Germany and used Bartram’s words. For example, Wordsworth’s poem “Ruth” describes “a youth from Georgia’s shore” who attempts to woo a maiden with flowery sayings derived from Bartram’s botany.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge relied upon the rich natural history details of the Travels for parts of the “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Coleridge’s famous “Kubla Khan” contains images from part two of Bartram’s Travels.

Bartram’s Travels established the importance of the American landscape as an alternative to the European Grand Tour. Readers of the Travels should remember that the book is not a strictly kept scientific journal, but a narrative of Bartram’s remarkable memories, his lasting contribution to the American intellectual tradition.

Native Medicines

Bartram traveled at a time when most European medicines were plant-based. When Bartram suffered a fever in Alabama in 1776, he sought a “febrifuge,” or plant tonic. An unnamed black servant guided him to stone-root, Collinsonia anisata, the roots of which he used on local advice. Bartram’s medical colleagues were especially interested in the properties of “black root,” or pickerel weed, a common aquatic plant in Florida. Like family friend and neighbor on the Schuykill River, Thomas Jefferson, Bartram was curious about Native American medicines made from plants.

Indian tonics Bartram mentioned in the Travels are:

- iris root (chewed for colds, indigestion, and heartburn)

- water lotus seeds (nutty flavored laxative)

- acorns and cornmeal (molded into a poultice for wounds)

- butterfly weed root (dusting powder)

- turkey pea (“creme” rinse for hair)

- brown-eyed susan (eye wash)

- fern rhizomes (for treatment of chills and rheumatism)

- mud (wound plaster)

William Bartram at Paynes Prairie

In Spring of 1774, William Bartram (1739-1823) moved westward from the St. Johns River to the Alachua Savanna, an area now known as Paynes Prairie.

The extensive Alachua is a level green plain, above fifteen males over, fifty miles an circumference, and scarcely a tree or bush of any kind to be seen on at. It is encircled with high, sloping hills, covered with waving forests and a fragrant Orange grove, rising from a exuberantly fertile soil. The towering Magnolia grandiflora and transcendent Palm stand conspicuous among them. Herds of sprightly deer, squadrons of the beautiful fleet Siminole horse, flocks of turkeys, civilized communities of the sonorous watchful crane, mix together, appearing happy and contented in the enjoyment of peace.

What were the main ideas of bartram’s travels

Gulf Coast Exploration, 1775 137

William Bartram left Mobile in the summer of 1775 (not 1777 as mentioned in Travels) “on board a large trading boat, the property of a French gentleman, and commanded by him (he being general interpreter for the Choctaw nation), on his return to his plantations on the banks of Pearl River. Our bark was large, well equipped for sailing and manned with three stout negroes, to row in case of necessity.”(138)

Upon entering “the channel Oleron [at present Grants Pass](139) between the mainland and Dauphin Island” (Mississippi Sound) “from this time until we arrived at this gentleman’s habitation on Pearl River, I was incapable of making any observations for my eyes could not bear the light.”(140) No indication of time for the journey is given.

It has been suggested that the Frenchman was Jean Favre, for a man with this name had a home one mile north of Pearlington on the Pearl River in western Mississippi. Three generations of Favres were Indian interpreters, first for the French from 1699, the British after 1764, and the Spanish after 1780.(141)

Since Favre traded with the Indians and all settlers for their pelts, skins, hides, etc., it is safe to assume he would on his return from Mobile have visited the rivers, bays and known homes of many settlers bringing sack cloth, leather, knives, axes, gunpowder, etc., or whatever they would have ordered on his way to Mobile.

The first bay and river they would have reached in Mississippi would have been the Pascagoula, then possibly the largest settled area on the Coast. The Krebs, De La Pointe, Boudreau, de Graveline, Dupont, Deflanders and possibly seven or eight other families plus slaves and Indians lived along the river. Irish settlers were arriving.

Along the shore of present Jackson County en route to Biloxi Bay at Belle Fontaine was the J. B. Baudreau family. Pierre and Maria Ronchon were on the Dog or Escatawpa River.

Around Biloxi bay, including present day Ocean Springs, d’Iberville, Biloxi and Deer Island were many other French speaking families including several Ladniers, Grelot, Carco, LaFontaine, Seymours, DeBuys, and possibly a dozen others.

In mid Harrison County at Bear Bayou or present Long Beach lived Widow Ladnier and family with Nicholas Ladnier at Pass Christian.

Further around the Bay of St. Louis the Saucier, Carriere, Morins, Ladniers, Favre, Necaise, and a few other families lived.

Going around Hancock County the main travel route into the interior of Mississippi was up the East Pearl River. Indian tribes and their descendants remained strong and noticeable particularly in Hancock County until the 1930s.

William Bartram remained three days at the Favre home without any improvement in his eye disorder. The Frenchman suggested that he see Mr. Rumsey, an Englishman on Pearl Island “who had a variety of medicines,”(142) about twelve miles away. Francis Harper does not believe that this was the present Pearl River Island lying off the mouth of Pearl River, but rather in an area bounded on the south by The Rigolets, on the north by Salt Bayou, and on the east by West Pearl River.(143) In any case, the island was located within the present boundaries of Louisiana.

Return to Mobile, 1775

Bartram apparently returned through the Mississippi Sound in late November, 1775, mentioning “the bay of Pearls, sailing through the sound betwixt Cat Island and the strand of the continent; the beautiful bay St. Louis…continuing through…the oyster banks and shoals of Ship and Horn Islands, and the high and bold coast of Biloxi on the main, got through the narrow pass Aux Christians, and soon came up abreast of Isle Dauphin…”(l44)

Footnotes

N.B. Page numbers for all Bartram quotations will be given in the following way: The first page number cited will be the page on which the passage appears in the first (Philadelphia 1791) edition of the book; the second page number will be the page on which the passage appears in Francis Harper’s Naturalist’s Edition. For convenience in checking the original source, Harper’s edition provides both systems of pagination. When third or fourth numbers appear, they refer to Harper’s commentary, also in the Naturalist’s Edition.

138. Bartram’s Travels, op. cit., p. 418, Harper, p. 265.

139. See Harper, Naturalist’s Edition, op. cit., p. 581.

140. Bartram’s Travels, op. cit., p. 419, Harper, pp. 266, 581.

141. For this account of Bartram’s travels in Mississippi, the Bartram Trail Conference is indebted to Mr. James Stevens for his Technical Study, “William Bartram’s Mississippi Visit,” 1978.

William Bartram

William Bartram (April 9, 1739–July 22, 1823), an artist-naturalist and author, was son of John Bartram (1699–1777). In 1773 Bartram embarked on a four-year collecting trip to the American Southeast and published an account of his travels in 1791 that became a classic text in the history of American science and literature. Bartram helped run the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the most important botanic garden of the colonial and early national period.

History

The son of the Pennsylvania Quaker naturalist John Bartram (1699–1777) and his second wife, Ann Mendenhall (1703–1789), William Bartram showed an early interest in botanical pursuits. As a teenager, William accompanied his father on collecting expeditions and made drawings of North American plants that the elder Bartram sent to colleagues in England and Europe. William’s drawings were greatly admired by contemporaries and were thought by many to rival illustrations produced by well-established British artists Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) and George Edwards (1694–1773). [1] Despite the praise William received for his drawing abilities, John Bartram saw it as a pastime, not a profession. In 1755, he wrote to his London friend and patron, the merchant Peter Collinson (1694–1768), “My son William is just turned of sixteen, [and] . . . it is now time to propose some way for him to get his liveing by[.] I dont want him to be what is commonly called A gentleman[.] I want to put him to some business by which he may with care & industry get A temperate re[a]sonable living[.] I am afraid Botany & drawing will not afford him one.” [2]

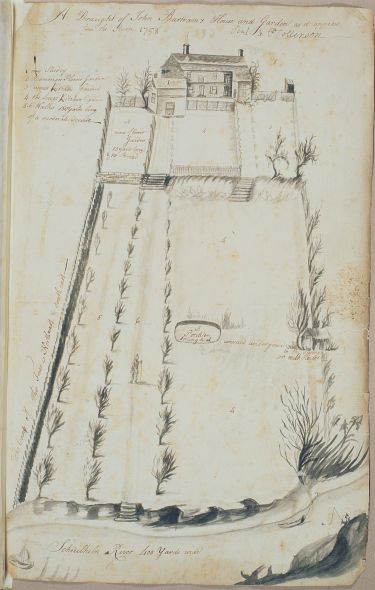

Fig. 2, John or William Bartram, “A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River”, 1758.

Taking a pragmatic approach to his son’s future, the elder Bartram apprenticed young William to Captain James Child, a Philadelphia merchant, from approximately 1756 until 1760. William continued to draw during this time and is likely the creator of the 1758 illustration of the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery at Kingsessing near Philadelphia [Fig. 2]. Although he was industrious in his apprenticeship, William’s subsequent attempt to establish himself as a merchant failed miserably. He had moved to Ashwood, North Carolina, and letters from that time speak to the difficulty he experienced: “I am unfortunate in ar[r]iving to a bad Markett, a wrong Season of the year, and the excessive rains has almost destroyed the Country,” he informed his father in May 1761. His fortunes did not improve, and in 1764 he explained to his older half-brother Isaac, “I would write to Father but I am afraid my Letters gives him Uneasiness.” [3]

In 1765, John Bartram was honored with the commission of King’s Botanist to the southern colonies, and he invited William to leave North Carolina and join him on an expedition through the Florida peninsula. William was so taken with East Florida’s landscape that he planned to establish, much to his father’s chagrin, an indigo and rice plantation along the St. Johns River. Despite his misgivings, John purchased tools, seed, and six slaves for William’s plantation, which met an even more ignoble end than his merchant business. The acres William acquired were swampy and stagnant, the weather unbearably hot, and he was plagued by illness, despair, and, quite possibly, profound guilt for a speculation premised on slave labor. After visiting William in September 1766, the Bartrams’ friend Henry Laurens wrote of his “forlorn state,” and he suggested John send additional provisions. Rather than continue to invest in William’s plantation, John encouraged him to return home to Kingsessing. [4]

William’s years as a merchant and planter left little time for drawing, but he quickly took up the practice after returning to the family home and garden. He began by making figures for Collinson, who actively sought out potential patrons for his young friend. He found one in the London physician John Fothergill (1712–1780), who would underwrite a nearly four-year botanizing journey through the Carolinas, Georgia, and East and West Florida. Between March 1773 and January 1777, William sent Fothergill seeds and specimens of subtropical plants, and at least 38 drawings of the region’s flora and fauna. Among the seeds he collected were those of a tree he and his father had encountered near the Altamaha River near Fort Barrington, Georgia, in 1765, which he wished to name Franklinia alatamaha [sic] [Fig. 3], after Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). William later recalled, “We never saw it grow in any other place, nor have I ever seen it growing wild, in all my travels, from Philadelphia to Point Coupe, on the banks of the Mississippi, which must be allowed a very singular and unaccountable circumstance; at this place there are two or three acres of ground where it grows plentifully.” The plant flowered in Bartram’s garden in August 1781 and, two years later, Bartram prepared a detailed description and botanical drawing of the specimen for the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus Jr. (1741–1783) ( ). Younger generations of naturalists tried to locate the plant along the Altamaha River but were unsuccessful; all existing specimens of the tree are believed to have descended from the seeds William collected. [5]

Once he returned from his extended botanizing expedition, William worked toward refashioning his field notes into a literary hybrid of natural history, travelogue, and religious allegory, which became his Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws; Containing An Account of the Soil and Natural Productions of Those Regions, Together with Observations on the Manners of the Indians, published in 1791. His Travels received mixed response from critics: published nearly fifteen years after his expedition, the plash and flow of the book’s language seemed out of place in a work of natural history, and many of William’s scientific discoveries had already been published by others. The book, however, was praised by Romantic authors and poets in America and Europe, who reveled in its rich description and verbal meander. [6]

When John Bartram died in 1777 the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery descended to William’s younger brother, John Jr. (1743–1812), but William continued to assist with business. [7] In 1783 he prepared a broadside list of the plant collection at Bartram’s Garden for publication in Philadelphia and, with the help of Benjamin Franklin, in Paris. The catalogue includes 218 plant species, most of which had been collected and planted by the elder John Bartram before his death. However, the list also includes “Three Undescript [sic] Shrubs, lately from Florida”: Philadelphus (Philadelphus inodorus), Alatamaha (Franklinia alatamaha), and Gardenia (Fothergilla gardenii), all species that William introduced to the garden after his travels to the Southeast. [8]

Sometime around 1786 William suffered a compound fracture of his right leg when he fell gathering cypress seeds in the garden, and the injury likely prompted his retirement from active physical labor. Under his influence, however, the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery became a significant site for an emerging generation of naturalists. [9] William became an important mentor to Benjamin Smith Barton (1766–1815), whom he had met just before Barton left to study medicine at Edinburgh University in 1786. [10] Barton later became the first Professor of Natural History and Botany at the University of Pennsylvania, a position that Bartram apparently declined in 1782. [11] Barton regularly brought his students to study specimens in Bartram’s garden, and William produced many natural history drawings for Barton, including a set of drawings to illustrate Linnaean botanical taxonomy that were engraved and published in Barton’s Elements of Botany (Philadelphia, 1803), the first botany text published in the United States. [12]

In 1806 Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) invited William to join an expedition to the Red River, but he declined “on account of [his] advanced Age & consequent infirmities (being towards 70 Years of Age) And [his] Eyesight declining dayly.” [13] He continued to mentor students and receive visitors at Bartram’s Garden, however, where he died in 1823 at the age of eighty-four. His niece, Ann Bartram Carr (1779–1858)—who, together with her husband Colonel Robert Carr (1778–1866), had run the garden since 1812—continued to operate the commercial nursery after her uncle’s death.

—Lacey Baradel and Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- , March 14, 1756, in a letter to Alexander Garden (Berkeley and Berkely 1969: 86) [14]

- , December 5, 1785, in a letter to Benjamin Franklin (Darlington 1849: 522–23) [16]

“I have taken the freedom to mention these proposals to thee knowing that thou was always ready and willing to promote any useful knowledge and science, for the use of mankind ; and if, on consideration of the premises, thou should approve thereof, thou may communicate them to the members of the Philosophical Society, or any other set of gentlemen, that would be willing or likely to encourage such an undertaking. Perhaps Congress, or some of the members, might promote their going out with the surveyors, when they lay out the several new states.

“I have ordered my nephew, the Doctor, to present thee with one of my Catalogues of the Forest Trees of our Thirteen United States; which I hope thou’ll accept of, for thy perusal.”

- , July 14, 1787, describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery and his encounter with members of the Bartram family—probably William and his brother John Bartram Jr. (1888: 1:272–74) [17]

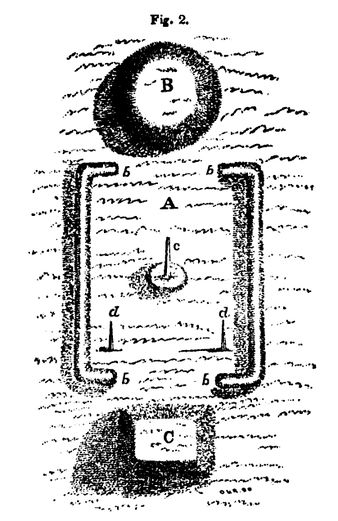

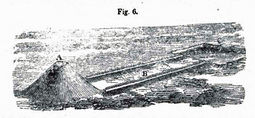

Fig. 3, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 52, fig. 2.

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1853: 51–53) [18]

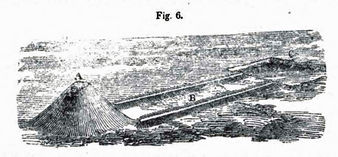

Fig. 4, A great mound and its avenues, at Mount Royal, near Lake George, Georgia, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 57, fig. 6.

- Bartram, William, 1789, describing Indian settlements in North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (1853: 57–58) [18]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing the area north of Wrightsborough, GA (1791; repr., 1928: 56–57) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing St. Simon’s Island, GA (1791; repr., 1928: 72–73) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Marshall Plantation, on the San Juan River, FL (1791; repr., 1928: 84) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian village in FL (1791; repr., 1928: 96) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Lake George, GA (1791; repr., 1928: 101, 104) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Lake George, GA, and settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1791; repr., 1928: 101–2, 407) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian town in Cuscowilla, GA (1791; repr., 1928: 167–68) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing a typical house in Cuscowilla, GA (1791; repr., 1928: 168–69) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing an Indian town in Georgia (1791; repr., 1928: 169–70) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing Indian village south of Charlotia (1791; repr., 1928: 250–51) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1791, describing settlements of the Muscogulge and Cherokee Indians (1791; repr., 1928: 406) [19]

- Bartram, William, 1792, describing islands off the coast of Georgia and Florida (1996: 93) [20]

- Niemcewicz, Julian Ursyn, March 24, 1798, journal entry describing the Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery (1965: 52) [21]

- Pursh, Frederick, 1814, describing a visit to Bartram Botanic Garden and Nursery in 1799 (1814: 1:vi) [22]

Images

William Bartram (illustrator), Tanner (engraver), Cornus Florida L., n.d.

William Bartram, Dionaea muscipula, n.d., engraving.

John or William Bartram, “A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River”, 1758.

James Trenchard after William Bartram, Franklinia alatamaha, c. 1786.

William Bartram, Arethusa divaricata, 1796.

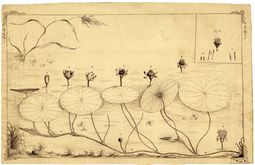

William Bartram, An Aquatic Plant [Brasenia purpurea (Mich) Casp.], ca. 1800.

William Bartram, Rhododendron punctatum, 1801.

William Bartram, Plan of a “plantation” (or “villa”) of a Creek Indian chief, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 38, fig. 1.

William Bartram, “Plan of the Ancient Chunky-Yard,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 52, fig. 2.

William Bartram, “Arrangement of the Chunky-Yard, Public Square, and Rotunda of the modern Creek towns,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 54, fig. 3.

William Bartram, Plan of a Cherokee Private “Habitation,” in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 56, fig. 5.

William Bartram, A Great Mound and its Avenues, at Mount Royal, near Lake George, Georgia, in “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians” (1789), from Transactions of the American Ethnological Society 3, part 1 (1853): 57, fig. 6.

Source https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/naturalists/bartram/

Source http://bartramtrail.org/page-1710339

Source https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/William_Bartram