What was it like to travel in the 1970s? What’s better? Then or now?

How did people travel in 1900 from US to Europe?

Traveling was not always as secure and carried such low risk as today. We will be looking at how people traveled from the United States to Europe from 1900 to 1950.

Transportation can be found everywhere in the United States of America. Transport is essential to our lives, getting from point A to point B, crossing the states, and even other countries.

Transportation in the 1900s or at least in the beginning of the century was mainly limited to horsepower and slow-moving trains. Still, now with the invention and advancement of automobiles, planes, trains, and boats, the vehicle has become much easier to use for long distances. This can be seen by the fact that there are now highways, roads, and airports in many parts of the world.

The System has improved to the point where ETIAS visa will become a central part of transportation internationally. It will help ensure the safety and the security of the country visited, supporting the fight against terrorism and other illegal, fraudulent activities. However, traveling was not always as secure and carried such low risk as today. This article will be looking at how people traveled from 1900 to 1950.

Transportation in the 1900s: Traveling from the USA to Europe

It was all about horse-and-carriage transport in the 1900s. Before the introduction of automobiles, the horse-pulled carriage was the most common means of transportation.

Because roads were scarce in the early 1900s, most visitors relied on waterways (mainly rivers) to get to their destinations.

The 1900s was the last decade until roads, canals, and railroad systems took off in the United States. This period represented a considerably slower and more ancient mode of transportation than the traditions we connect with the rest of the twentieth century.

The 1910s

In the 1910s, as ocean liners became increasingly prominent, cross-continental traveling became more common.

In the 1910s, the steamship was the only means to travel to Europe. The Titanic was, of course, the most renowned ocean liner of the decade.

The Titanic, the giant ship that was supposed to act as a means of transport from Europe to the United States of America, set sail from Southampton, England, on the 10th of April and was scheduled to reach New York City on the 17th of April.

It crashed into an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on the 14th of April and sank three hours later in the North Atlantic.

Even when the ship was built, it was the world’s most extensive hand-made means of transport and the pinnacle of 1910s travel.

The 1920s

The Roaring Twenties introduced us to the beauty and adventure of travel. During World War II, railroads in the United States were enlarged, and travelers were urged to take the train to travel to out-of-state resorts.

It was also a prosperous and prosperous decade, and it was the first time that middle-class families could buy one of the essential travel luxuries: an automobile.

Even while improved train travel goes back to the 18th century when George Pullman developed the idea of private train cars, luxury trains were introduced in the 20s in Europe, owing to the design splendor of La Belle Epoque.

Finally, after the problems of 1912, ocean liners gained such prominence that the Suez Canal was widened. Travelers would primarily cruise to places like the Bahamas and Jamaica.

The 1930s

We arrived in the 1930s when airplanes first entered the mainstream travel landscape. While the Wright brothers invented the plane in 1903 and commercial airlines became available in the 1920s, flying was a confined, unstable experience restricted only to the wealthiest segments of society.

Flying in the 1930s was a little more comfortable (though still reserved for the wealthy and business travelers). Flight cabins grew, and seats became more luxurious, mimicking living room furniture.

The Douglas DC-3, which debuted in 1935, was a commercial airplane that was bigger, more pleasant, and quicker than anything else travelers had seen. TWA, Delta, United, and American were among the airlines that used the Douglas DC-3.

The 1930s also marked the beginning of trans-Atlantic flights. Pan American Airways was the first airline to ferry passengers over the Atlantic, starting commercial flights in 1939.

The 1940s

The era of road trips started in the 1940s when automobiles improved. Cars were growing larger, higher-tech, and more luxurious, from luxury vehicles to some well-made family station wagons.

Because improved automotive comfort enabled lengthier road trips, the 1950s saw a significant expansion of highway options in the United States.

The 1950s

President Eisenhower introduced the Interstate system in the 1950s.

Before the creation of the “I” roads, travelers could only travel across the country on the Lincoln Highway (Which was built and let you travel from New York City to San Francisco).

However, the Lincoln Highway wasn’t a comfortable ride, with parts of it being unpaved, which is one of the causes the Interstate system was created.

President Eisenhower was under a lot of pressure from his supporters to upgrade the roads, so he did so in the 1950s, opening the way for more comfortable commutes and road trips.

Other News

ETIAS Will Improve the Passenger Experience

Long queues for passport control are unpleasant for travelers. ETIAS will improve the travel experience by reducing wait times at international borders. Systematic changes will help prevent delays, and implementation of ETIAS online application by 2023 will make travel to the Schengen area easier for millions of visitors, including U.S. citizens.

- Mar 29, 2022

- 3min read

9 major airports in Italy

Italy has 77 airports in total. However, not all of them present convenient options for international travelers. You can find 9 major airports in Italy international tourists can enjoy during any season.

- Oct 17, 2022

- 11min read

What are the goals of the EU?

Europe 2020 is another program for long-term socio-economic growth. Its primary goal is to develop and strengthen the economies of all members. This will be done based on the knowledge that has been recognized as an important factor in determining modern economic competitiveness.

- Aug 7, 2022

- 21min read

© 2022 etiasvisaapplication.org All rights reserved.

© 2022 etiasvisaapplication.org

All rights reserved.

We use cookies on our website to give you the most relevant experience by remembering your preferences and repeat visits. By clicking “Accept All”, you consent to the use of ALL the cookies. However, you may visit “More info” to provide a controlled consent.

/*! elementor – v3.7.8 – 02-10-2022 */ .elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-stacked .elementor-drop-cap.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-framed .elementor-drop-cap.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap-letter.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap-letter

We warn users (hereinafter, “you”) that cookies are used on the Website (hereinafter, “our/this Website”).

The accompanying Cookie Policy describes how the Website, which is owned and run by ETIASVISAEUROPE.ORG, uses cookies (hereinafter, “we”).

We recommend that the user examine this policy frequently because it may be updated due to new regulations or business reasons.

Why do we utilize cookies, and what are they?

“Cookies” are file formats that are used for various reasons, including adjusting the Website’s format to your computer, gathering statistical data, enhancing your user experience, and so on.

You consent to the establishment of cookies by visiting and browsing this Website and purchasing the services offered.

These include session cookies (which are automatically deleted when you close your browser), persistent cookies (which are stored on your device for a long time), owned cookies (which are sent to your device by our Website to collect data for our use), and third-party cookies (which are sent to your device by a third party) (service providers we have contracted, e.g., links to social media to reshare our content).

Cookies for the login process, cookies for data protection, cookies for authentication or identity, add-on cookies, user interface cookies, and certain session cookies are exempt from such permission.

Please be aware that if you modify your browser’s settings by deactivating the constraints placed on installing cookies, we will presume you give us your permission. Furthermore, your consent will not be necessary if the placement of cookies is essential to provide a service on our Website that you have specifically requested.

Third-party cookies are subject to the Privacy and Cookies Policies of the third party. We are not responsible for the content or authenticity of the third-party Policies mentioned above.

The following cookie types may be installed in your browser by us:

- Technical cookies enable the management and operation of our Website, as well as its features and services, such as carry-out purchases, payment management, social media content sharing, and so on.

- Analytical cookies let us understand how you use our site and which data or services you are most interested in, so we can improve your overall experience.

- Advertisement cookies help us improve the quality of our Website’s advertisements

| Cookies name | Supplier | Type | Storage Period |

| Authorization | Owned | Technical | Session |

| Matomo | Matomo | Analytical | 2 years |

| pk_id.15.d0ee | ETIASVISAEUROPE.ORG | Analytical | Session |

| _pk_ses.15.d0ee | ETIASVISAEUROPE.ORG | Analytical | Session |

| _pk_ses.16.9Ab8 | ETIASVISAEUROPE.ORG | Analytical | Session |

| _pk_ses.16.9Ab8 | ETIASVISAEUROPE.ORG | Analytical | Session |

What choices does the user have when it comes to blocking or refusing cookies?

You can withhold your consent to the set-up of cookies from this Website at any time by changing the settings on your device’s browser.

For the most popular internet browsers, here are links to instructions on how to manage or erase cookies:

- Google Chrome

- Mozilla Firefox

- Microsoft IE and Edge

- Apple Safari

- Chrome for Android

- Opera

Please remember that if you disable cookies, you will lose access to certain Website functions that rely on cookies.

You may also set your smartphone’s browser to allow or reject all types of cookies automatically. You can also set your browser to inform you whenever a cookie is received, allowing you to choose whether or not to accept it.

You can also enable private browsing, which prevents your browser from saving browsing data, website logins, cookies, and other information about the web pages you visit, and non-tracking browsing, which prevents your browser from tracking your visits and user patterns.

What was it like to travel in the 1970s? What’s better? Then or now?

At a time when travel as we knew it feels like a remnant of the past, I find myself reflecting on my early international travel experiences of the 1970s. Musings about what it was like to travel ‘back then’ have been inspired by faded photographs posted on Facebook by friends from that era who are spending part of their Covid-19 isolation sorting through their 50-year old relics.

Table of Contents

Highlights of travel in the 1970s

My international travels began with a five-week voyage across two oceans from Australia to the United Kingdom. By the end of the decade, I’d settled in Canada so in one sense, they never ended.

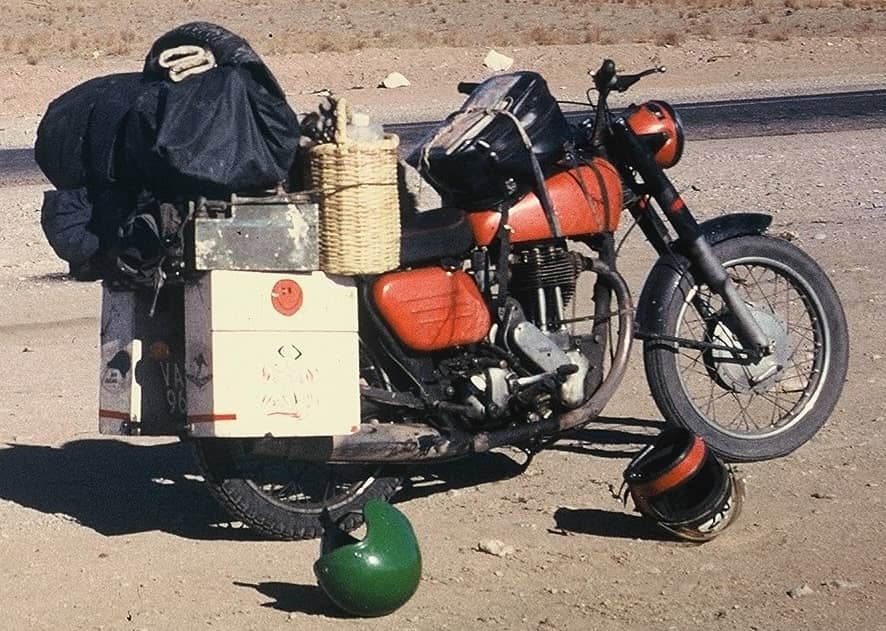

Much of it was of the independent variety, dominated by limited planning and shoestring budgets. Tours weren’t part of the picture. Hitchhiking was common, and jumping freight trains, although enjoyable, less so. Travel by motorcycle and an endless string of Volkswagen Kombi vans were popular choices of the time.

What was it like to travel in the 1970s?

1. Europe was on our radar

From Australia, Europe was an obvious choice as a travel destination. Asia, while closer, wasn’t as popular. Until Australia’s White Australia policy was finally abolished in 1973, it was one of the cornerstones of the country’s approach to immigration. Unfortunately, its underlying assumptions about race and ethnicity were embedded in its citizens’ perception of its neighbours. Much of Asia was viewed as a place of poverty, danger, and political instability. The American War in Vietnam was raging, and the cultural familiarity of Britain, with its easy entry requirements, made it a more popular destination for young Australians and New Zealanders from the antipodes. Our self-imposed limits on attractive travel destinations were propelled by Eurocentric perceptions and values.

2. Five weeks on a ship to get to Europe

In 1972, a one-way ticket from Australia to Britain cost 400 AUD by air or sea (in a six-berth cabin from Sydney on the SS Australis). According to the Australia Inflation Calculator, that’s valued at 4,250 AUD in 2020. To a 22-year-old, the choice was a no-brainer. Five weeks of room and board and six ports of call in six countries was the way to go. Those 9-cent beers and endless partying had nothing to do with it.

3. It involved at least a year or two of travel

When did the gap year become a thing? It wasn’t a factor in my choices, or those of any of the travelling friends I had the good fortune to accumulate along the way. We finished high school, chose a vocation that usually involved post-secondary studies, worked for two or three years, and saved enough money to travel for an extended period.

Before deregulation of the airline industry in the late ‘70s, air travel was expensive. Once fares were no longer set by governments and airlines no longer had monopolies on routes, it opened up travel to the average person. Until that happened, Europe was expensive to reach so it wasn’t a destination to contemplate for a short period.

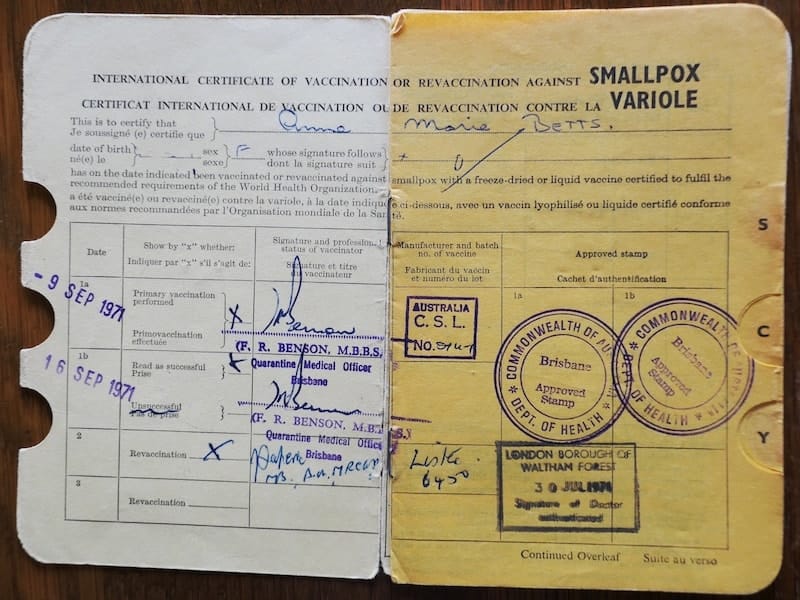

4. Smallpox vaccinations weren’t pleasant

After 3,000 years of human infection, smallpox was finally declared eradicated in 1979. Until then, it was the world’s most feared disease. In the 20th century alone, it’s estimated to have claimed 300 million lives. The thirty percent fatality rate was part of the story. The other involved the potential loss of eyesight and the painful development of pus-filled lesions followed by pitted scars.

In 1971, the prevailing recommendation for international travellers departing Australia was to be vaccinated against smallpox, cholera, and typhoid. Because the smallpox vaccine left behind a distinctive scar, many people chose the inside of the arm by the elbow for the site of inoculation. That was my choice. I recall keeping my arm outstretched for several days to avoid bumping the ugly pus-filled lesion and subsequent scab.

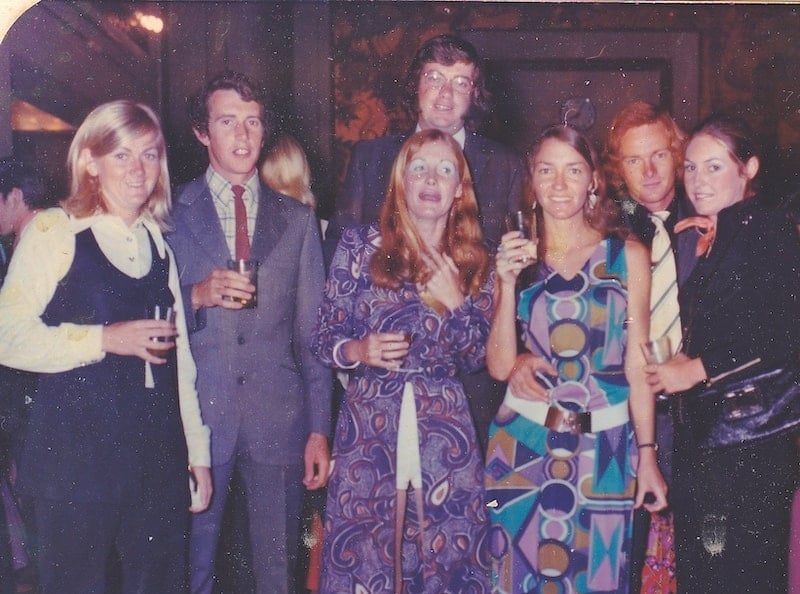

5. We lived with lots of other travellers

By the time the SS Australis berthed in Southampton in February 1972, my group of potential flatmates numbered seven. While crossing the Atlantic, we had agreed to look for a flat together in London and share accommodation and living costs until the summer.

After summer travels, our group expanded to ten the following winter. In our flat in the Stamford Hill area of London, we’d each contribute our share of the rent and food costs to a jar in the pantry, in cash.

Most of the women were teachers who finished work earlier than the guys so delineation of tasks associated with shopping, cooking, and doing dishes were structured along gender lines. The women shopped and cooked, and the men took care of cleaning up after the evening meal. With ten mouths to feed, and lots of drop ins, picking up supplies required planning and coordination.

Before the Covent Garden market became the trendy place it is today, fresh produce was sold by the box or sack, much of it from the backs of farmers’ trucks and lorries.

We lived in close quarters, with only one bathroom. I have no recollection of drama or conflict. There were no cliques. We depended on each other for camaraderie, friendship, social interaction, and ability to keep to a budget. Our social tentacles reached into ten different workplace circles. Conversation was never lacking. Neither was intel on the latest party, concert, theatrical production, or where to get fake student cards. We travelled together on weekends and breaks, and cross-pollinated our respective travel dreams.

These living arrangements were pivotal points in our ability to get on with others, and built a solid foundation for lifelong friendships that endure to this day.

6. It was a time of a political awakening

In 1972, the voting age in Australia was 21. By the time the federal election rolled around on December 2, 1972, the Aussies in our group were both eligible and eager to cast ballots in our first election. Voting at Australia House in London was a momentous occasion, on many levels. It was an exciting time, politically. After 23 years of successive Liberal-Country Party governments, the possibility of change was in the wind. The charismatic leader of the Labor Party, Gough Whitlam, outlined a reformist platform that included extricating Australia from the ‘war of intervention in Vietnam,’ abolishing conscription, providing tuition-free university education, establishing a universal health insurance system, pursuing land rights for indigenous Australians, and eliminating the remaining vestiges of the White Australia policy. These, and others, were initiatives that appealed to us, and fronting up to Australia House to cast our ballots felt like we could actually have a role in their implementation. When the Labor Party won the election, it felt as though our votes had single-handedly swept our party of choice into government. It was the first and last time I voted in an Australian election, but It was a political awakening. I realized the importance of familiarizing myself with the issues, and the power of my vote.

7. Travel plans took time to unfold

When travel was actually booked, with no internet we relied on travel agents, booking agents, brochures, and postal mail.

It sometimes required physically presenting oneself to get the necessary information. When travelling through Central Turkey on the way to Iran in November ’73, we encountered temperatures so brutal that continuing on the motorcycle was out of the question. The sound of a train in the distance offered a glimmer of hope that an alternative might be possible. Obtaining the schedule and information on whether or not the bike could be carried as baggage required a 70-kilometre ride from Göreme to Kayseri to find out that the next eastbound train would pass through Kayseri the following day.

8. Visas took time to get

Forget about showing up at the border of some countries and gaining entry. And e-Visas were decades away. Lining up visas took months of planning, especially for extended periods of travel. We’d have to take our passports to an embassy, consulate, or diplomatic mission, or mail them in and wait for them to be returned.

I recall being the envy of other passengers with my Mexico and US visas. By the time the SS Australis docked in Acapulco, it had been 20, 18, or 16 days since passengers had boarded in Auckland, Sydney, and Melbourne respectively. I remember a cheesy ‘Miss Australis’ beauty pageant when contestants were asked about their life goals. The response “To get off this bloody ship!” resonated with many folks. I was thankful my friend Kris and I had planned to disembark in Acapulco and reboard in Fort Lauderdale seven days later. Had we not taken our passports to the US consulate in our home city of Brisbane, or mailed them to the Mexican Embassy in Sydney, this wouldn’t have been possible.

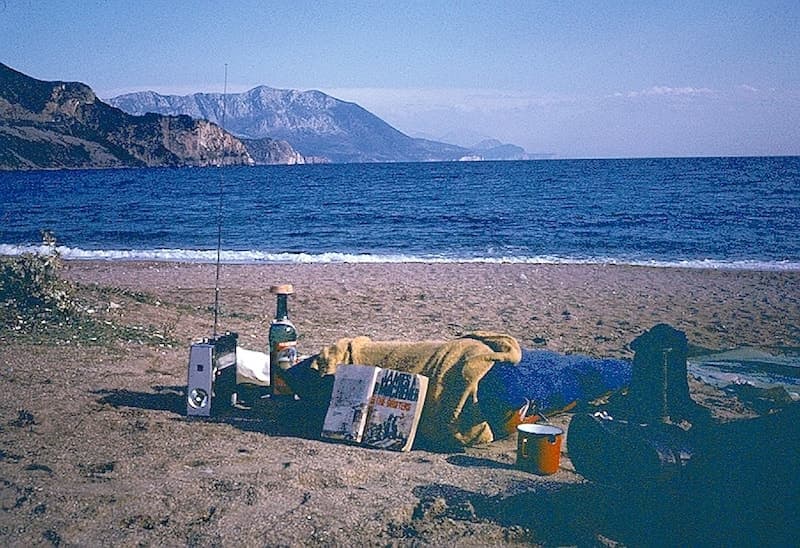

9. Mass tourism didn’t exist

A beautiful beach was more likely to be deserted or have a few Kombi vans parked on the foreshore. My most prominent memories are of beaches along the stunning Adriatic coast of the former Yugoslavia, and sleepy coastal villages scattered along the southern coast of Turkey. They were places to camp for a few days, wash and air out clothes and sleeping bags, hang out with other travellers, and devour several chapters of a recently acquired novel. Today, they’re more likely to be dominated by resorts with access limited to paying guests.

I don’t recall sharing places with crowds, except in Munich at the 1972 Olympics and the ’72 and ’73 Oktoberfests. Now, at the peak of the global pandemic as 2020 slides hesitantly into 2021, the announcement of the cancellation or postponement of these events would have been inconceivable in the ‘70s.

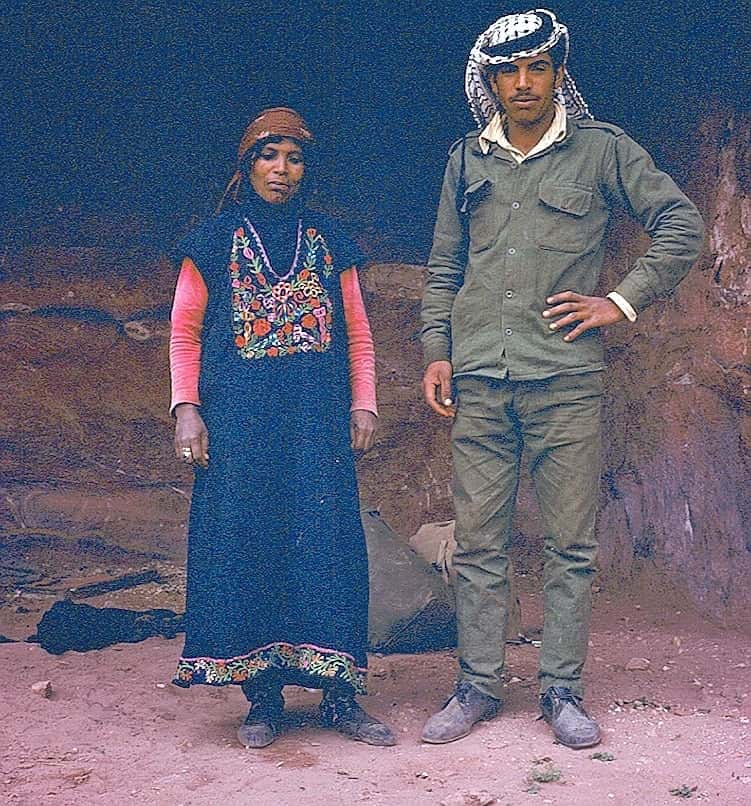

Today’s popular tourist spots such as Ephesus in Turkey, Auschwitz in Poland, or Petra in Jordan attracted very few visitors.

At Ephesus, the night watchman, Hüseyin Sömen sprayed our tent pitched at the gates to discourage what we presumed would be an influx of insects during the night. He extended an invitation for us to join him in his tiny hut for tea and snacks. We didn’t share a common language but it didn’t matter as we somehow managed to chat for three hours. The next day, Hüseyin gave us a private tour of the archeological site in Turkish and German. We didn’t understand either; human kindness, generosity, and his pride in Ephesus we did.

At Auschwitz in 1973, we virtually had the place to ourselves. In fact, when leaving, we asked about a spot to camp and the attendant indicated we could pitch our tent in the parking lot. Today, the concentration camp memorial is so popular that there’s an online reservation system to control the number of visitors.

Petra? There was no entrance fee and very few tourists. I was hitchhiking with Hans, a German traveller I met at a hostel in Amman. In Petra, Bedouin tribes inhabited the area, living in caves or tents woven from goats’ hair. We were befriended by Ishmael, a young B’doul Bedouin about our age who took us to his family’s cave for supper cooked over a fire fuelled with camel dung and sticks. He guided us to far-reaching sites, showed us a cave where we could sleep and enjoy several pleasurable hours with him and a friend over tea and conversation.

When Petra became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the mid-1980s, the Bedu were relocated to the resettlement village of Umm Sayhoon. Today, their presence in Petra is most visible as tour operators or merchants selling souvenirs to tourists.

10. Paper plane tickets were the norm

We guarded those suckers like we did our passports. Lose them and you were in trouble. They consisted of several sheets of red carbon copies. Each page was ripped off with each soon-to-be-completed flight segment.

I cringe at the recollection, but there was the time I’d left our tickets at home, 550 kilometres away. It was during the Christmas break from teaching in the Canadian North. Thank goodness a helpful Air Canada agent was gripped with the Christmas spirit. She pulled out all stops to drum up replacement tickets to see us from Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia and back.

Oh, and planes had the ludicrous arrangement of smoking and non-smoking sections. The near-universal ban on smoking on airlines was two decades away.

11. Not all ferries were the roll-on-roll-off variety

It would be a strange concept today, but not all vehicular ferries provided the option to drive on and drive off. Loading and unloading involved vehicles’ being unloaded over the side in a sling.

In 1973, the ferry across the Irish Sea from Wales to Ireland unloaded our Kombi in this way. The TS Leda across the North Sea from Tynemouth to Bergen used a similar process to unload our motorcycle a few months later.

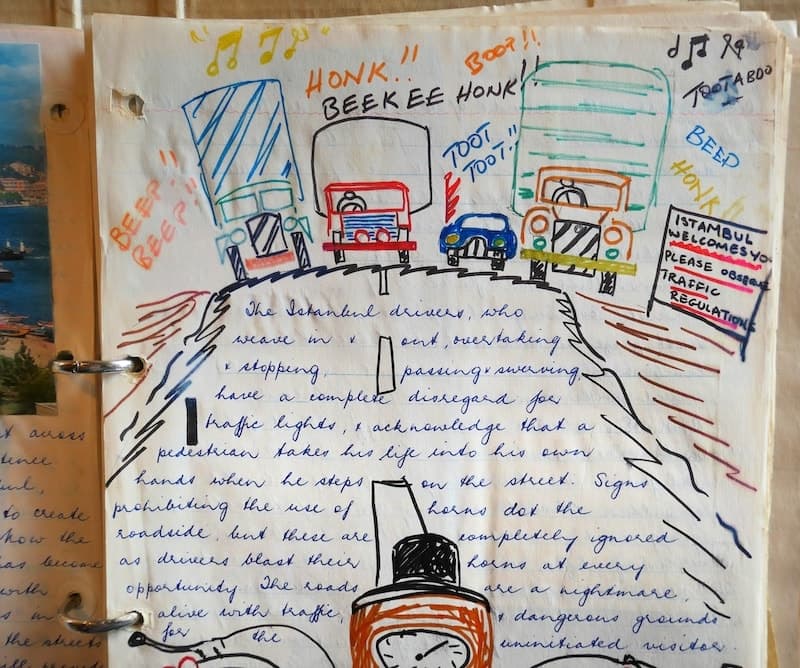

12. Travel guides were limited

Europe on 5 Dollars a Day was our bible. By the time we reached Istanbul, travel guides had dried up and we relied on the recommendations of other travellers. Hanging out at The Pudding Shop and regularly scouring the notice board helped shape onward plans.

Or, we’d borrow whatever materials and pamphlets other travellers happened to have and make notes on the highlights. At an Istanbul campsite in ’73, I recall poring over a collection of borrowed resources on Asian Turkey by candlelight.

13. Plans were loose and changeable

We’d have a rough idea of where we were heading and how long it might take to get there. Our vehicles were acquired cheaply, usually from travellers who were heading home and looking for a quick way to unload what they couldn’t take on a plane. As a result, breakdowns were frequent.

At the end of the ’72 Oktoberfest, I joined two friends, Jo and Rhyll, for a spur-of-the-moment decision to drive from Munich to Istanbul. Our £30 purchase of a Kombi got us across the border into Austria before it succumbed to the negligence of its owners who failed to check the oil level of the engine.

All our wheels had a name; this short-lived one was called ‘Sebastian,’ a moniker that came with the registration papers.

The demise of Sebastian necessitated hitchhiking back to Munich for a more expensive £90 investment in a second van. Regular checks of the oil and a healthy dose of good fortune saw us to Istanbul and back to London to find work over the winter. This diehard returned to Europe and the USSR the following year before she gave up the ghost in Rome. She was called ‘Fanny.’

When hitchhiking, the availability of rides sometimes determined the destination. From the ferry port of Limassol in Cyprus, we chose the side of the road with the most traffic. I was hitchhiking with Rosalie from Vancouver, another kibbutz volunteer. It worked to our advantage, and led to a few nights’ sleeping on the Six Mile Beach near Kyrenia. It was there we heard of two job opportunities as ‘bar, grill room, and swimming pool attendants’ at a family-run business on the northern coast. It overlooked the quaint former Greek Cypriot village of Orga, transformed into the Turkish Cypriot village of Kayalar following the 1974 Turkish invasion. Rosalie and I scored the jobs, and stayed in a room above the house of the President of the village who was also the barber. As a result, our predicted 10-day stay on the island extended to two months, ending a few weeks before the invasion.

From a chance roadside meeting with Iranian Ali Mohammadi on the outskirts of Istanbul in ’73, we replaced the plan to visit what was now war-torn Israel with three months in Iran. This was during the Shah monarchy, before the Islamic Revolution of ’79. Visas were easy to obtain, and westerners were welcome. Iranians stopped us on the streets, eager to engage us in conversation and practise their English.

When presented with the opportunity to trade our motorcycle in Iran for three Persian carpets, we grabbed it and said goodbye to our cantankerous two-wheeled friend ‘Ernie.’

All this to say, there were no commitments associated with employment, homeownership, or family obligations; our choices were primarily driven by how far our meagre savings could take us. Financial security and planning for retirement weren’t on the agenda. We were in our early twenties; we lived for the moment and left those kinds of mature choices until later.

14. Travelling companions were collected along the way

Safety, finances, companionship, and convenience influenced the selection of travelling companions. For some, romance was part of the picture. Decisions to travel together emerged from conversations in a London flat, hostel common room, kibbutz dining room, or roadside encounter.

15. Book trades were a social endeavour

E-books and audiobooks were decades away. Printed books were heavy, so there were limits on what we carried. Novels were traded with other travellers. Only those worthy enough to earn a strong recommendation made the cut.

I remember my excitement at discovering the historical fiction of Leon Uris. It inspired future travel. Uris’ deep research provided a rich historical context for many of the places we yearned to visit. Exodus was an impetus for a trip to Israel and Palestine, and Mila 18 to the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. Serendipity intervened several months later when I walked into an office in Tel Aviv to volunteer to live and work on a kibbutz. I was sent to Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, dedicated to Mordechai Anielewicz, the young commander of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Book trades came full circle to forge meaningful connections through the transformative experience of travel.

16. Travel quashed preconceived ideas

Something that hasn’t changed is that travel unlocked minds and opened up new ways of thinking and seeing. It expanded one’s worldview. One early youthful revelation concerned the countries that were the major sources of Australia’s post-war immigration boom. Greece, Italy, and Yugoslavia stand out in particular. I grew up believing that Australia was the greatest country on earth, and assumed these contributing countries had so many blemishes that they warranted leaving.

What I found in each was stunningly beautiful scenery, a rich cultural heritage, amazing food, fantastic architecture, history oozing around every corner, and friendly welcoming people. It didn’t take long to realize that Australia, or no country for that matter, had a right to claim to be the greatest of them all.

17. Tea and biscuits were staples

Conversations with other travellers invariably involved a cup of tea. We’d stop by a Kombi with German plates, a motorcycle with Italian ones, or an old London taxi sporting a GB or NZ sticker. It was an excuse for morning or afternoon tea, even if the clock indicated otherwise.

The same held true for merchants, nomads, and other residents in Turkey, Jordan, and Iran. Hospitality and tea were integral elements of social interaction and we enjoyed many positive encounters as a result.

After pitching the tent and cobbling together supper, we’d wile away the hours with our neighbours and new friends over tea and biscuits. Beer and wine were luxuries in most countries; tea we could afford.

18. Conversation was key

Conversation was essential to gathering intel about all things travel. We knew how to ask questions, a skill I find lacking in today’s world. We were curious about where people were from, their previous adventures, and where they were headed. Questions unlocked what we had in common. There was no internet to distract or inspire us; we relied on questions, conversation, and storytelling to forge relationships and shape our travel dreams.

19. Several address books were filled

Contact information was stored in small address books, essential accessories for the regular postcard-writing activity. Names and addresses were collected along the way so our address books filled up quickly, with multiple amendments for friends on the move.

20. We survived on a limited travel budget

My travelling companion Des described our travel budget as being smaller than a gnat’s nostril. There was no margin for the extravagances of guided tours, expensive experiences, eating in restaurants, or exploring the bar scene. Munich’s Oktoberfest was the exception. There was ample room in the budget, if not our constitution, for those one-litre steins of magnificent German lager.

Accommodation costs were minimal. The Kombi was parked in back streets, parks, fields, or on beaches until the prospect of hot showers lured us into campgrounds.

While travelling by motorcycle, in cities we stayed in campgrounds. Outside urban areas, camp was set up in forests, amongst scrub, in caves, on beaches, or wherever we could pitch a tent. In Turkey near Denizli we slept under a bridge, and in a tomb at Pamukkale. In the Sinai at Eilat, we commandeered one of the coveted clumps of palm trees that provided ample protection from the elements. In the freezing temperatures near Persepolis in Iran, the tent was more valuable as a blanket for sleeping under the stars.

21. We survived without Facebook and Instagram

Social media didn’t exist. In a way, it was a blessing. We weren’t constantly plugged in to a home we’d intentionally left behind. There were no ‘instagrammable’ images beckoning us to follow the hordes to sites of mass tourism, or a digital universe to stifle our capacity for independent discovery. Destinations weren’t shared with influencers or ordinary travellers who packed fashionable wardrobes for capturing self-promoting photographs beside iconic landmarks. Selfie sticks didn’t exist so we didn’t have to witness people taking unnecessary risks for extreme selfies or ‘the perfect shot’ to garner as many likes as possible. If travel was regarded as a competition or a checklist in the ’70s, social media wasn’t a platform to promote it. And hunting down Wi-Fi to access it was an albatross several decades into the future.

I’m pleased our generation didn’t have to think about the unchecked power of social media, and whether or not we had to succumb to the pressure of using it to influence or profile our travels.

22. Water wasn’t packaged in bottles

We escaped one of the greatest cons of the century, and as a result, didn’t have to encounter an endless supply of discarded water bottles along the way.

Water was available from taps, fountains, and natural places. In Yugoslavia, just outside Titograd, I recall going in search of water from our camping spot amongst scrub. Finding access to the stream beside the road turned out to be an exercise in futility. Stumbling across a house and pointing to my empty water container to kids playing in the yard brought me to a couple of guys drinking beer out back. Biscuits, cheese, beer, interesting conversation without a common language, and a full water container later, I was on my way. All without contributing to the scourge of discarded plastic bottles.

23. Poste Restante figured prominently in our plans

I remember the joy of receiving a fistful of correspondence from home or our wanderlusting friends. Those were the days when mail addressed to a person’s name, Poste Restante, name of city/town and country, was delivered to the main post office. The Poste Restante was also a meeting place. In Munich in ’73, it was a place for a scattered group of friends to meet at several specific days and times on the eve of Oktoberfest.

Mail was the only way to confirm arrangements or send regrets. Returning daily for an entire week to the post office in Kyrenia to find out when my friends would arrive was filled with anticipation and excitement. Eventually, Graeme and Rhyll’s postcard arrived with the news they’d changed plans and were bypassing Cyprus.

On a trip to Cambodia in 2017, nostalgia struck at seeing a Poste Restante window. I thought they were vestiges of the past.

24. Aerogrammes and postcards were communication staples

Do aerogrammes still exist? They were blue with six panels, including two for addresses, and packed with news. There was no spell check, so crafting them took time. I can still recall the taste of the glue on the flaps.

Does anyone write postcards today? I don’t. But back then, postcards were the communication of choice on the road. We’d grab a bulk purchase deal, and head to the post office for stamps. Writing and mailing them took coordination. Time would be carved out to find a comfortable place to write quick summaries. They’d have to be mailed while the postage stamps were still valid, before crossing a border. Today, my handwriting wouldn’t cope after decades of tapping away at a laptop or phone/tablet keyboard.

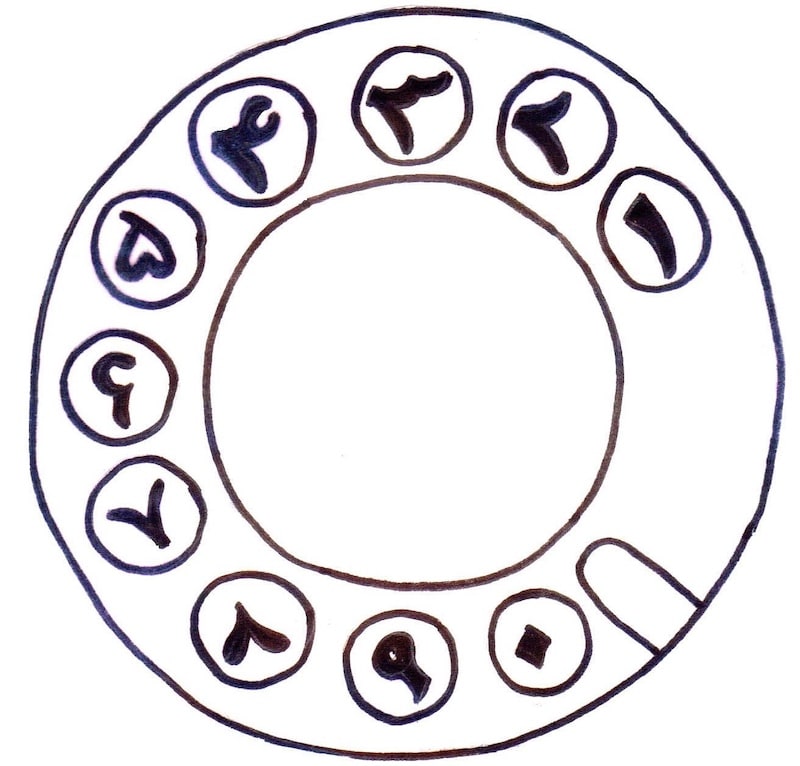

25. Telephone calls were rare

Using a telephone was costly, and call quality was questionable.

Some systems weren’t intuitive, and instructions in a foreign language unhelpful. A call to an international school in Tehran to suss out job prospects was made more complicated by the unfamiliar dial. Nevertheless, it was so interesting that it warranted reproduction in my journal.

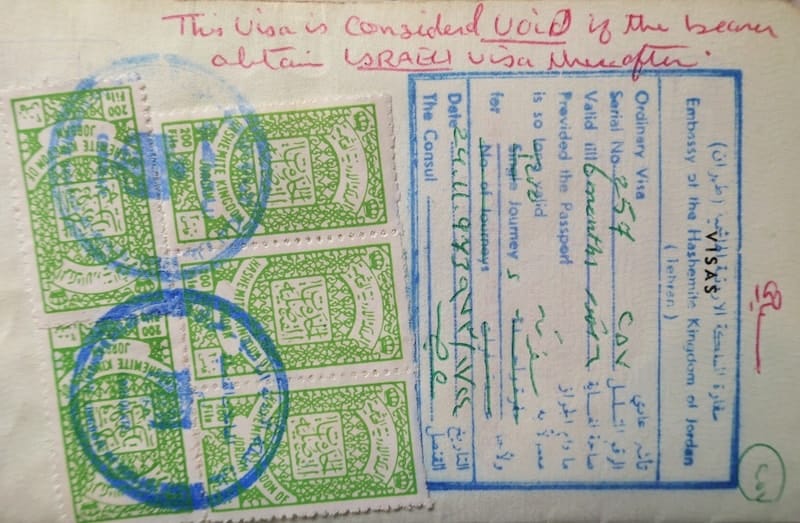

26. Passport stamps were important

Passport pages filled quickly with visas and entry and exit stamps. They were as important for where we’d been as for where we were headed.

We collected them religiously and admired them with awe. They were badges of honour. Today, I don’t give them a second glance.

However, a visa or stamp of a previously visited country could raise flags for officials. My Israeli arrival stamp posed a serious problem for Jordanian police, with threatened deportation after crossing through the militarized zone at the Allenby Bridge. I should have known better. The Jordanian visa had a clear annotation, “This visa is considered VOID if the bearer obtains ISRAELI visa thereafter.” Technically speaking, it wasn’t an Israeli visa but semantics meant very little considering the significant and deeply rooted political context. In the end, I was granted permission to stay in Jordan and return to the West Bank by the way I came.

27. A divided Europe

The Cold War led to a divided Europe and fortified borders. Travelling behind the Iron Curtain was complicated. It required multiple visas, compulsory currency exchanges, and rules on where we could cross or spend overnight.

In 2013, I cycled through four countries on the Danube Waltz by Bike and Boat tour. Were it not for the boarded-up buildings and weeds growing in the traffic lanes of an old border crossing, it would have been difficult to identify at which point we crossed from Austria into Slovakia. There was no need to carry passports on our bike and boat journey across four countries. For someone who had passed through these countries in the ‘70s, it was quite the revelation.

28. A divided Germany

In 1972, visiting Berlin by road involved crossing from West Germany into East Germany (German Democratic Republic or GDR/DDR). Reaching West Berlin from the Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing required passing through the 180-kilometre GDR corridor. Armed guards, boom gates, and observation towers were ever-present reminders of a strong police and military presence. While in transit through the corridor, it was forbidden to take photographs or deviate from the highway. Stopping was permitted only in designated parkways.

We were stopped nine times by GDR authorities for vehicle and passport checks at various points along the corridor.

A divided Berlin was another eye-opener. Beside Checkpoint Charlie, the strip of no-man’s land was a sombre reminder of Germans who had lost their lives trying to cross. The dilapidated buildings on both sides of the wall seemed to be waiting for a time when urban regeneration could restore Berlin to its former glory, without a wall separating the two pulsating hearts aching to be one.

29. Taking photographs required constraint

Film was expensive, and getting it developed was costly. Frugality was key when deciding whether or not to take a photograph. It cost money to find out if we had a winner or a dud, long after we’d visited a place. Quality of the better photographs was poor compared to the digital versions of today. It was virtually impossible to take a selfie, and besides, film and processing cost far too much to waste on self-indulgent narcissism.

Why did we take all those slides/transparencies? So we could bore people with a slide show after the trip? Whatever the reason, I have a sizable collection. I invested in a slide scanner upon retirement and digitalized those that were somewhat recoverable.

30. For the most part, airport security didn’t exist

My first brush with airport security was in Istanbul for my El-Al flight to Tel Aviv in 1974. Hijacking had emerged as a political weapon with serious repercussions for travellers. The deadly terrorist attack on Israeli athletes and officials at the Munich Olympics in 1972 had significantly raised the bar on security for El-Al as an airline, and all flights into Israel.

But security screening was targetted. In Istanbul, Des walked on the plane bound for London with no obvious security measures in place. I, on the other hand, was subjected to interrogation, frisking, and a painstaking examination of everything in my bag. It was so alien to anything I’d experienced that it warranted several pages in my journal.

31. Jumping freight trains was possible

My train-hopping adventure started from an exit ramp in Vancouver with a wave accompanied by a flippant gesture with my hitchhiking thumb towards a worker on a passing freight train. His response signalled an invitation to come on board. It was all we needed to scurry across the field and jump on the slowly moving train. Several trains, a variety of freight cars and 24 hours later, we arrived in Edmonton.

Jumping freight trains is illegal and dangerous. To ill-prepared young adventurers with high risk-tolerance thresholds, it felt exciting. It was, and meeting interesting railway workers enriched the experience. Just before Jasper, we were invited into a caboose to warm up and share conversation and stew with two engineers. One of them was a former RCAF pilot who’d crash-landed in France during World War II, and from their many decades of railroad experience they regaled us with stories. So it was with regret we had to quickly grab our gear at their announcement that our next train was just leaving the Jasper rail yards for Edmonton.

I would speculate that today, security measures would be more stringent and railway workers more constrained by company policies. Besides, the risks of financial penalties, imprisonment, and personal injury aren’t worth it. Back in the ’70s, our youthful ignorance and naivety didn’t give these considerations a second thought.

32. We were out of touch with world news

We relied on word of mouth, or the headlines of English language newspapers. For the most part, we were oblivious to what significant events were happening around the world.

Radio broadcasts kept us informed when we found a working radio with reception. In 1973, Des and I bought a shortwave radio in Munich that we planned to sell or trade in Istanbul. It was on a beach in Yugoslavia that we learned of the Yom Kippur War of 1973. As we were on our way to Israel, the news captured our interest. That notwithstanding, the conflict had all the elements of a serious international crisis involving among others, the two nuclear superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. From that moment, we became news junkies tuned to the BBC over the days ahead.

33. Travellers’ cheques came with challenges

We didn’t live on credit or use credit or debit cards. ATMs didn’t exist. Travellers’ cheques were safer than cash, but not as convenient. Our motorcycle barely made it to a gas station in Turkey after several attempts to find a vendor who’d accept them. I think we made the last few kilometres on fumes and downhill cruising.

34. Journalling was a daily event

With retirement, I enjoyed dusting off my collection of diaries and reading the musings of my twenty-something self.

The earlier diaries were mostly in cheap exercise books. I had a penchant for recording the mundane, such as what we ate and when we found a shower. The later ones were more interesting, with dialogue, lame attempts at poetry, and more descriptive accounts of people and places. Investing in glue and scissors for clippings and memorabilia made journalling more enjoyable, and drawing materials facilitated my ability to tap into the talent of travelling companions.

35. Music wasn’t accessible on the road

In the early ’70s, compact discs (CDs) were still two decades away. Cassettes had emerged as a more compact alternative to LPs, and our preferred format for prerecorded music. Portable players were large and bulky; the first Sony Walkman was released in 1979.

So our favourite music wasn’t something we listened to on the move. That had to wait until our return to London, or wherever we’d find work to fund the next travel adventure.

I was fortunate to share digs with some talented musicians. Steve showed me how to play a few chords on a guitar, and Annette introduced me to the music of Gordon Lightfoot, among others. Ralph McTell’s Streets of London became a perennial favourite, if not a signature tune of our ‘London 1972’ gang.

Tickets to live concerts were affordable. They weren’t extravagant productions involving dancers, elaborate lighting, special effects, and mega screens. In fact, I recall that Ralph McTell (or perhaps it was Don McLean) was accompanied on stage with a bass player — just the two of them. I saw Leonard Cohen at the Royal Albert Hall, Carole King at the Hammersmith Odeon, Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young at Wembley Stadium, and Elton John at a rinky dinky picture theatre not far from our Finsbury Park flat. I enjoyed performances of so many of these icons and more, at what feels like a fraction of the price of today’s concerts.

Another thing that hasn’t changed relates to the memories a particular song evokes. It takes us back to a different time and place. For me, this is the case with Don McLean’s American Pie released in November 1971. On reaching Houston in January 1972, we discovered it as a huge hit. By the time we reached London the following month, it had reached the top of the UK charts. Under our Finsbury Park flat, The Brownswood Park Tavern played it incessantly well into the night. Whenever I hear American Pie today, those recollections surface.

36. Lifelong friendships were formed

Friendships forged on the SS Australis have endured to this day. Our regular reunions in either New Zealand or Australia attract two-dozen or so friends accumulated during those earlier travels, with smaller get togethers in between.

Hugs, conversation, laughter, and camaraderie dominate each gathering, and the years melt away as we piece together the rich memories of our youth.

Which is better… then or now?

Was travel back then better? Do I prefer travel in my seventies compared to that of my twenties? There’s no definitive answer to either question. It’s just different.

But, I have to admit; there are things about the ‘old days’ I miss. And, there are things I don’t. My memories are sprinkled with both.

I was a member of a privileged generation. Race and youth worked to our advantage. That didn’t include the 20-year-old Australian men whose birthdays were drawn for conscription into ‘national service’ and a free trip to Vietnam. For the rest of us, travel was within reach and jobs were plentiful. And, for the most part, they were unionized jobs with decent benefits and working conditions. As a result, the vast majority of my 1972 cohorts enjoy decent pensions while riding out the global pandemic.

What do I miss most about travelling in my twenties? It felt safer. It probably wasn’t, but our youthful naivety and misplaced confidence in our invincibility led to risk-taking I wouldn’t consider today. Along the same lines, what few material possessions I had weren’t worth much, so very little was invested in keeping them secure.

What do I like most about travelling today? It’s not without its pitfalls, but I love how technology makes travel easier. I can look up the weather, transportation, opening hours, and how to get from A to B at any time. I can book and pay for travel within minutes. I can satisfy my curiosity by looking up something on the fly. I can communicate in real time across borders at no cost, or in a foreign language with the help of Google Translate. The wealth of information on the internet makes me a more curious and better-informed traveller.

Final thoughts

A world that felt so accessible to travellers until early 2020 remains in jeopardy. I find myself reflecting on travel I’ve taken for granted, and future trips I assumed would always be options.

I wonder what air travel and the cruise industry will look like, and how many travel operators will be around when the world starts travelling again. Will the public’s appetite for international travel return to previous levels or will international flights and destinations be abandoned in favour of campgrounds, hiking trails, bike paths, and destinations closer to home? Will cities such as Barcelona and Venice that were hard hit by the pandemic and buckling under the weight of mass tourism look as attractive to visitors as before? Or, will residents who reclaimed their cities during the pandemic mount pressure to limit the number of tourists in future?

When the time comes to venture into a post-Covid world, things will be different. As for timing, I hope borders will be open and it will be safe to travel to a reunion to meet up with friends in March 2022 in Australia, the 50th anniversary of our life-changing voyage on the SS Australis.

If you enjoy travel stories of the past, take a look at:

- The book that changed my life

- Rekindling friendships through travel

Might you be interested in more travel stories from this era? In 1973, I travelled with New Zealander Des Molloy for five months on an old 1957 Norton motorcycle. If you enjoy reading chronicles of motorcycle travels, check out Des’s recent works. The Last Hurrah: From Beijing to Arnhem is available as a DVD and book package. No One Said It Would Be Easy: A youthful folly across Americas on old bikes describes an adventure in the late ’70s. Check out Kahuku Publishing Collective for more information.

Ganja and “S.H.I.T.” (Suspected Hippie In Transit): Backpacking Southeast Asia in The 70s

Following on from our popular article about London lad Barrie Scott who backpacked Southeast Asia in the 60s, we brought on the fearless Aussie, Ian H, to tell us how backpacking Southeast Asia was in the 70s and early 80s!

The Outback might have prepared him for the snakes hiding in his room, but the SHIT (Suspected Hippie In Transit) label is another story altogether…

Journeying on the roof of local buses, being engulfed by the fumes of passengers smoking ganja while airborne and relying on local news to get around, we interviewed Ian from his home in Melbourne…

Read Next: (opens in new tab)

What motivated you to go backpacking to Southeast Asia?

When I was seven years old, my mum gave me a hardback children’s encyclopedia for Christmas with a bright yellow cover and five images from around the world: The Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, an Afghani in a turban, a Chinese rickshaw and the Pyramids at Giza. I decided there and then that I wanted to know why those people dressed that way, where they lived and why? (I still have the book somewhere in my library.)

At Uni, I was a member of the Monash University Malay and Indonesian Club (MUMIC) where many students took annual trips to Indonesia, studied and stayed at the University of Salatiga in Central Java.

Some students, like my girlfriend Sue and I, preferred to be more independent and go backpacking with our own schedule and itinerary for the three months in between university years.

Back then students did not actually take gap years, but often began backpacking and never returned to university! So at the age of 19, I set off for my first overseas journey…

Ian and his girlfriend Sue in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1979

What ideas were circulating in the Western world of Southeast Asia at that time?

Southeast Asia was viewed as a completely untamed, wild part of the third world — full of poverty, political instability and danger.

Southeast Asia and India were famous for stories of incredible dysentery, cholera, typhoid and tropical illness. Many people feared travelling to Asia. The shadow of the Vietnam War still hung over that region. Other than very adventurous travellers and students, most tourists stayed close to the developed cities such as Singapore, Bangkok and Hong Kong.

Hong Kong was seen to be very exotic and wild enough to visit without getting into too much trouble! Thailand, on the other hand, had a vigorous trade in heroin and was viewed by most people in Australia at the time as a pit of sin and depravity.

Today in Southern Thailand, there are ‘moon’ parties, jungle parties, beach raves and many other excuses to get totally wasted with various drugs. This isn’t different to the 70s and 80s when hash cookies, mushrooms and ganja were freely available (yet highly illegal in Southeast Asia).

Bangkok had been a well-known destination during the Vietnam War in the 1960s for “Relief and Recreation” (“R and R”) travel for US soldiers. During that period, an intense trade in prostitution and drugs had developed, a trade which some say continues to this day.

What did your family and friends think of your decision to travel?

My parents were horrified, but they knew Sue and I would travel regardless of their opinions. (Isn’t that true of most young wanderlust backpackers?)

Asia was seen as a place where backpackers disappeared and were never seen again! Parents were paranoid about their children being caught up in the drug trade and being locked up in a Southeast Asian prison.

It wasn’t like drugs were something “exotic” in my neighbourhood and something that my parents had no idea about. I had grown up in a part of Melbourne during the ’70s, where teenagers were selling drugs by the kilo. One set of parents we knew supplied morphine for a schoolmate’s 14th birthday to “liven things up.” I knew teenagers who were dealing quantities of drugs equal to four months average salary. But even so, travelling to Asia was not something my parents were thrilled about.

Our friends and peers were completely cool with us travelling; Australians were already famous for being adventurous. It was a natural progression in my friends’ eyes that Sue and I should venture into Southeast Asia and beyond.

From the age of seven, I was roaming around the outback of Melbourne, so backpacking came pretty easily. We had a bunch of mates who did the same and it was “de rigour” to head off to Asia the second university finished and to arrive back on the latest possible day before classes started.

The hope was that you arrived back from Asia without “Bali belly” or some other tropical problem such as typhoid, malaria or cholera.

How did you navigate around Asia?

When we travelled, the Lonely Planet Guide to Southeast Asia by Tony and Maureen Wheeler was in the process of being written and published.

The first real travel book was written by a guy named Bill Dalton, and it had a pure black cover, like a bible (it was actually referred to for years as Dalton’s Bible.

Dalton’s personal guide was a remarkable tomb of information about Indonesia, but very out of date with prices and timetables. Sue and I travelled to some of the outer islands in Indonesia such as Sulawesi and Sumatra, but the further away from the mainstream backpacking trail we strayed, the more inaccurate Dalton’s Bible became. Some of the maps were so incorrect that it was unbelievable that they were the same towns or cities.

However, the lovely thing about the Bible was that Dalton named the owners and staff of hotels, restaurants and in some cases, you could actually meet the people in the book. One such person was Ibu Canderi, who ran Canderi’s Losmen (now a homestay and restaurant) in Ubud, Bali. Canderi’s was one of the first losmens (small guest houses usually run by local families) in Ubud.

In 1978, we ate at Ibu Canderi’s on advice from Dalton’s Bible and in 2012, I asked my daughter when she was visiting Bali to see if Canderi’s still exists. She met Ibu Canderi and sent me a photo of the two of them. I later visited Ibu Canderi in January 2014, and she claimed to remember me from 1978. I’m not sure she did, but it was lovely to see her after 36 years and know that Canderi’s was still rocking and rolling, feeding and housing backpackers and the like.

Rex Hotel in Singapore, about to return home after three months backpacking Southeast Asia.

Where was the first place you landed in Southeast Asia and what was it like?

We landed in Denpasar, Bali on the first fully chartered STA student flight from Australia.

The flight we took from Melbourne to Denpasar was completely out of control. I think we were on a Boeing 707, and I can remember when the door closed, the steward — who was a real character — clapped his hands, looked around and said, “Let’s party!”. You can imagine what 181 students all on one inaugural flight, and just about to have the adventure of their lifetime, were like!

During the whole flight, people were drinking beer and passing joints across the aircraft. The whole plane stunk of dope and there was a blue haze from one end of the plane to the other. (Can you imagine that today!?)

By the time we arrived, after the five-and-a-half-hour flight from Melbourne, nearly everyone was either drunk or stoned. It was a pretty wild flight. I am not sure if anyone joined the mile-high club, but I would not have been surprised.

When we arrived in Denpasar, Sue and I headed off to Kuta Beach, which was a village about 200 meters from the beach. At night you could walk under the moon and palm trees and just sit quietly and listen to the surf. Kuta actually has fairly dangerous rips, but most Aussies were good swimmers, so it wasn’t an issue for us.

Which places in Southeast Asia left an impression on you?

I loved visiting Phuket and staying right on the beach. We stayed at Kata Beach near Karon Beach. The year we stayed there, there were only 90 bamboo bungalows on Kata beach and the surrounding area. I don’t think there were any bungalows or buildings at Karon Beach, so imagine the whole of Phuket with just 90 huts!

To get out to Kata and the Karon beach area, we had to ride on an old truck converted into a bus on dirt roads. For the hell of it, I rode on the roof with the locals and the luggage. Sue and I used to wash at a well near our bungalow, and there was only one restaurant, which was actually built on the sand out of palm branches with a rough wooden frame.

There were sea snakes, which were pretty frightening, as well as snakes that took refuge in the ceilings of the grass huts. I almost stood on a snake one morning. Another time, there was a scorpion on the platform at the well where we used to wash. We were told not to venture into the long grass or near the paddies because there were cobras.

What was transportation back then like?

Transport outside of main towns was either in the back of a truck or a covered utility. In Indonesia, there were many Japanese mini-vans designed for nine people, with up to 25 people jammed inside and hanging off the sides or roof. The 1.2- and 1.4-litre motors were pushed to the limit.

Everyone would be there. Sometimes there would be five people in the front seat. Occasionally massive calico bags of rice would be thrown in with the passengers and other produce, as well as fighting cocks in cages, babies in sarongs, children and elderly people.

Friends of ours had taken one flight where the pilots were arguing with each other about where they were located. The door of the cockpit was open and one of the pilots pulled out a paper aeronautical map and started to make calculations with the map spread across the controls. The plane, carrying our terrified friends, eventually landed half an hour late.

We were once flying in the middle of a monsoon and hit a lot of turbulence. It is one thing to be in a jumbo or an A380 in monsoonal weather but it is another story in an old turbo-prop. The plane was dipping and diving and tilting like a veritable roller coaster.

After about 40 minutes, the plane stank. Not only adults and children upchucking, but also the “Transmigrasi” people (locals being transported to other areas of the country by the government), most of whom had never been in a bus let alone seen or travelled in an aircraft.

Many of the adults had actually been so terrified that they had either crapped or pissed their pants. It was an unbelievable stench, and we felt really sorry for these terrified people. The storm was very severe and I really was not sure of our chances of a safe arrival.

Eventually, we landed about 20 minutes late, which was a long time in the days of limited excess fuel. I am pretty sure we must have been on the absolute edge of the fuel tanks.

After we arrived, one of the funniest things was watching the luggage arrive on the conveyor belt. Most of the Transmigrasi people had never seen such a device. When bags started to appear through the wall, people were astonished. One guy straddled the conveyor belt and waddled his way to the wall to look through the rubber strips to see what was behind the magic wall. It was hilarious.

After a few bags, pigs, roosters and chickens began to appear in various combinations of cane baskets. We realised that the hold must have been full of prized pets and farm animals. It was the first and last time that I saw pigs and chickens at an airport conveyor belt arriving as checked luggage.

What was accommodation like?

In some parts of Java and Thailand, a lot of accommodation doubled up as brothels. It was not uncommon to stay somewhere where some rooms were marked for tourists, and others for 24-hour sex nests for other types of guests.

I remember a place in Solo (also called Surakata) in Central Java, where the hotel had a wide corridor and walls made of a material not much superior to cardboard. There was a women a few rooms away who spent most of her day in a cotton nightgown sitting outside of her room.

Each room had a table and two chairs out the front, plus an endless thermos flask of sugary tea. We were naïve at first and assumed that she was another resident, but later realised that the number and frequency of visitors to her room meant a different type of occupancy. Prostitution was rife throughout Indonesia and Bangkok was famous for prostitution even then.

Many of the rooms in hotels had high ceilings and wall mirrors—one room also came equipped with stirrups, if that takes your fancy.

Sue in the hammock outside a grass hut at Kata Beach, Phuket

Did locals welcome travellers in the 70s?

We felt very welcome throughout southeast Asia, and we had a particularly warm welcome in Indonesia because Sue and I both spoke the language. We could chat with people, crack jokes and were able to have a very different experience to most tourists. We also learned a little bit of Thai; enough to order meals, find a room and ask for basic help.

To this day, I believe that learning the language can really help in getting to know the locals. Off the beaten track in Java, you had to be very careful, polite and respectful of local culture. Indonesia is a very liberal Islamic country, but women had to ensure their wrists and shoulders were covered when travelling. Bare shoulders or the display of elbows was an absolute no-no in small towns and villages.

One time we had a bunch of kids throw rocks at us because we were foreigners and they did not think that Sue was appropriately dressed. They were just being kids, harmless and playing up.

Was there a big backpacker scene at the time?

Yes, the big adventure was to travel overland from Australia to London. The tricky bit was that it was dangerous to travel through Iran and Turkey.

The Iran border seemed to open and close on a whim, and people were detained frequently. There was periodic fighting and it was very difficult to get up-to-date information with no internet and limited access to international news. Overseas phone calls were wildly expensive and very difficult to make from isolated locations. People who travelled overland would have to rely on local news to find out if it was safe to travel onward.

On the backpacker trail, people would go missing occasionally, never to be seen again. It was also dangerous for blonde-haired women in some parts of Asia and the Middle East, so many women used to dye their hair black to travel overland to London, or to travel throughout Africa.

Did backpacker hubs like Khao San Road exist back then?

Khao San Road was one of the first big backpacker hangouts in Asia. Jalan Jaksa in Jakarta was famous, as well as Phuket and Ko Samui in Thailand. Kuta Beach was significant, as was Yogjakarta in Java, and Lake Toba in Sumatra for their “Sumantran Gold” dope.

Batu Ferringhi in Penang was a great location for backpackers, but the Malaysian and Singaporean Governments were publicly against hippies. On arrival, there were large signs listing the characteristics of hippies as a warning to travellers. Some of what I remember, included…

HOW TO IDENTIFY A SHIT: (SUSPECTED HIPPIE IN TRANSIT)

- Men who have hair below their shoulders. (I had long hair halfway down my back at university. When I went to Asia, I had it cut because I would not be allowed to enter Singapore otherwise.)

- Men or women who do not wear underwear. (It was important that female travellers wore bras, otherwise they would be considered hippies and liable to deportation. Also, if men wore baggy shorts and it was obvious that they had no underwear on, they would usually be taken away for interrogation to discover if they really were a hippie.)

- Men or women who wear wooden shoes that are not part of a traditional costume. (This was a reference to clogs, which were very popular at the time, but considered hippie attire unless you were Dutch.)

- Men who wear earrings. (I had both ears pierced and always took my earrings out when travelling.)

- Men or women who do not wash.

A badge of pride for many backpackers was that they were initially refused entry to Malaysia and had a large stamp in their passport by the Malaysian Government. The stamp took about one-third of a page and was an acronym, “SHIT,” which stood for “Suspected Hippie In Transit”. If you were labelled “SHIT,” then you had three days to leave the country.

When I first visited Penang, there were regular stories in the Butterworth Press and The Straits Times about hippies and their depraved habits, deportation stories and being identified after “pretending to be tourists.”

I read one hilarious article along the lines of, “How will the Malaysian Government identify hippies who cut their hair?” It was a very serious article about those dastardly hippies who were disguised in short hair. Even though the hippie issue was well known, plenty of backpackers refused to dress up for immigration and were duly harassed or deported by Malaysian officials.

Rickshaw to cross the Thai Malay border near Kota Batu.

How many times have you travelled to SE Asia since 1978 and what changes have you witnessed over the years?

I have travelled regularly through Asia for more than 30 years. For me, the biggest changes are with infrastructure and economic development.

I lived in Indonesia during the Asian economic boom and in two years (1994 to 1996), Jakarta built more than 200 buildings higher than 30 stories, as well as shopping complexes and freeways. This would be the equivalent of London building 15 Canary Wharfs in two years or rebuilding the whole of downtown San Francisco in the same period. I have never seen anything close to that type of development.

Throughout Southeast Asia back in the 70s, the electricity and gas supplies, sewage and water supplies were problematic. The establishment of modern power stations meant that industrial development and factories could expand. Also, the improvements in port facilities meant greater imports and services not only for locals but also for tourists. These developments have changed wealth, skills and education, as well as social mobility throughout Asia.

One of the big downsides of development, however, is the massive increase over the years in pollution and environmental degradation at popular tourist destinations.

In many parts of Southeast Asia, governments struggle to invest in or be able to manage environmental degradation. In the 1970s and before, a lot of takeaway food was wrapped in banana leaves which people would throw on the side of the road. The leaves would decompose quickly in the tropical environment, but banana leaves were quickly replaced with plastic bags.

Also, some tourist locations cannot manage the volume of sewage and rubbish, so it is either poured into rivers or dumped offshore. For backpackers reading this – your rubbish counts!

Which place do you think has changed the most?

This is a difficult question. Most of the cities in SE Asia have been radically transformed in the last 30 years. From photos I have seen, Phuket physically has none of the beauty or characteristics of the 1970s and ’80s other than the same ocean, the same sky and lovely local Thai hosts.

Ian outside the Losmen Puri Muwa in Monkey Forest Road, just near Canderi’s – 1978.

Nusa Dua in Bali is basically a small city now and the same goes for Kuta. The beauty of the beach and the acres of coconut palms were destroyed many years ago.

Needless to say, people still have wonderful holidays and experiences in those locations, however, there is very little left of the original landscape or day-to-day culture for tourists to experience.

There is barely anything left of the old Singapore, the colonial architecture, palm trees and jungle. Singapore was one of the most charming and exotic cities in the world but is now highly advanced and high-tech. Beautiful in a different way I guess.

The culture, languages and personal identity of each country in Southeast Asia remain very strong, but there is a pervasive re-creation of western fashion, music and media. With globalisation, this can’t be helped.

Have backpackers themselves changed?

I think that tourists and backpackers, in general, are far less adventurous than they used to be and crave the luxuries and amenities of home. A lot of travellers focus more on selfies and uploading pictures immediately to Facebook or Instagram than interacting with the people around them.

In the 1960s and ’70s, backpackers often did not have any news from home for six weeks or more. No news at all. Prior to the internet and mobile phones, communication with home was made by having letters sent to “Post Restante” — mail-holding service for tourists — at post offices along the route. Most post offices would keep your mail for four weeks before sending it back to the return address.

One of the funniest places that I picked up mail was in Kathmandu. The mail was in alphabetical order in boxes on a table the equivalent size of about three dining tables. However, the post office was not privy to reading English names. So nearly all of the mail was under “M” for “Mr.,” “Ms.,” “Miss” or “Mrs.” It took quite a while to find your mail!

Did you backpack Southeast Asia in the 60s, 70s, 80s or 90s? How have things changed? Share your thoughts in the South East Asia Facebook Community!

Join Over 20,000 Happy Backpackers in Our Facebook Group!

Find travel buddies. Get advice. Have all your questions answered by travellers on the ground in Southeast Asia right now.

Source https://www.etiasvisaapplication.org/how-did-people-from-the-us-travel-to-europe-in-the-1900s/

Source https://packinglighttravel.com/other-travel-tips/travel-in-the-1970s/

Source https://southeastasiabackpacker.com/backpacking-southeast-asia-70s/