Columbian Exchange

Columbian Exchange

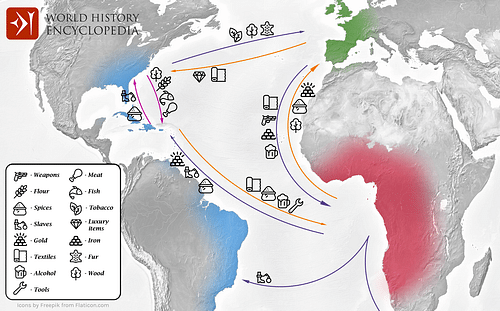

The Columbian exchange is a term coined by Alfred Crosby Jr. in 1972 that is traditionally defined as the transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the Old World of Europe and Africa and the New World of the Americas. The exchange began in the aftermath of Christopher Columbus’ voyages in 1492, later accelerating with the European colonization of the Americas.

Columbus’ Arrival

The Americas had been isolated and cut off from Asia at the end of the last Ice Age approximately 12,000 years ago. Apart from occasional contact with Vikings in eastern Canada 500 years prior to Columbus and Polynesian voyages to the Pacific Ocean coastline of South America around 1200, there was no regular or substantial contact between the world’s peoples. By the 1400s, due to rising tension in the Middle East, Europeans began the search for new trade routes led by Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394-1460), who sailed southward along the west coast of Africa, establishing trading posts. The Portuguese goal was to sail around the southern tip of Africa into the Indian Ocean to directly access the markets of India, China, and Japan.

Advertisement

The biological consequences of European exploration & settlement were the most significant impacts of the interaction.

An Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506), sailing under the flag of Spain on behalf of Ferdinand II of Aragon and his wife Isabella of Castile, proceeded westward across the Atlantic Ocean in search of direct routes with the same markets in Asia. Columbus and his ships departed Spain on 3 August 1492, making a brief stop in the Canary Islands for provisions and ship repairs, before commencing the 5-week voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. On 12 October, Columbus and his crew made landfall in what is now the Bahamas on an island that the native people called Guanahani, which Columbus renamed San Salvador. Following Columbus’ first journey, the Spanish, and later other Europeans, began settlements in which they attempted to recreate their Old World lifestyles and cultures in the Americas.

On Columbus’ second voyage (1493-1496) domesticated animals – horses, cattle, pigs, chickens – were introduced to the New World for purposes of food and transportation. The subsequent establishment of sugar, rice, and later tobacco and cotton plantations formed a new basis for wealth and trade. The accidental exchange of diseases, especially those carried by the Europeans, spread to the indigenous peoples resulting in the catastrophic deaths of upwards of 90% of all native peoples.

Advertisement

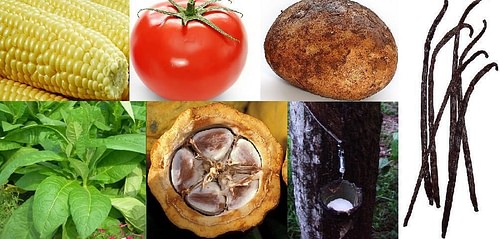

Plants

In terms of plants, Europe had experienced its own exchange phenomenon 5,500 years earlier. The origins of world agriculture can be traced back to over 12,000 years ago, and farming was firmly established in Europe by 4,000 BCE. The crops brought to the Americas by the Europeans in the late 1400s and early 1500s served to satisfy European demands to recreate their traditional diets but would also disrupt New World agricultural systems.

The Spanish initially introduced wheat, olives, and grapevines in order to produce bread, olives, and wine, staples of the Spanish diet and intimately tied to their Catholic rituals. In time, additional cereals and sugar would cross the Atlantic, allowing Europeans to create large agricultural plantations first in the Caribbean and later spreading to Mexico and throughout the rest of the Americas. When the European-based indentured servitude system drawn from the poor, debtors, and criminals failed to provide enough labor, Europeans also enslaved indigenous peoples to work the plantations. This approach failed, too, as the native peoples were not used to the physical demands of large-scale agriculture, ran away from the farms, and were dying in high numbers due to disease exposure. The Europeans then turned their attention towards Africa, resulting in the nearly 400-year phenomenon of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Africa supplied not only people for work but contributed to the exchange of plants by introducing rice, bananas, plantains, lemons, and black-eyed peas, creating additional sources of food and wealth for colonists and agricultural enterprises.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The Americas also provided Europe, Asia, and Africa with a rich variety of new foodstuffs. Maize, potatoes, beans, tomatoes, peanuts, tobacco, and cacao (chocolate) were among the plants that journeyed eastward across the Atlantic. By the 1530s, tobacco, smoked and inhaled (in the form of snuff) by Native Americans, became a very valuable cash crop, especially in the British Middle Atlantic colonies. Cacao was used by the Olmec, the Maya civilization, and cultivated in Aztec agriculture. The cacao bean was ground into a powder and infused into water creating a very bitter drink, which was disliked by Europeans. Hernan Cortés (1485-1547) brought cacao back to Spain in 1528. The Spanish added sugar and honey to alleviate the bitterness, and in the next hundred years, as it spread throughout Europe, vanilla was added to the mixture producing a new luxury item: chocolate.

The potato had the greatest impact on Europe affecting both their diet and lifespan. Potato consists of essential vitamins and nutrients, and it can grow in a wide range of soils capable. Producing high yields, the introduction of potato ended centuries-old cycles of malnourishment and famine, leading to higher population growth in Europe.

Advertisement

The discovery and use of quinine by Europeans assisted them in their future colonial adventures in Africa. Native to the Andes mountains region of Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia, the cinchona tree’s bark contains an alkaloid that provides effective medicinal treatment against malaria-carrying mosquitos. The discovery by Dr. Thomas Thomson in 1841 and the use of quinine by Europeans helped to cut in half the rate of deaths among European colonizers in the Africa and Pacific Ocean areas of colonization.

Cayenne, bell, tabasco, and jalapeño peppers derive from the capsicum pepper found in Bolivia and Brazil. Arriving in Europe after 1493, capsicum spread throughout South and East Asia and was adopted into the traditional cuisines of many European and Asian countries including Hungary (paprika) and Korea (kimchi). Medicinal uses of peppers have proved to be as valuable as their culinary adaptations. Capsicum offers the necessary requirements of vitamins A, B, and C; aids digestion by increasing the amounts of saliva and gastric acids; and is now used for pain relief for cases of arthritis, toothaches, and certain repository illnesses.

Tobacco, initially thought to possess medicinal value, was used in the American colonies as a currency for a short while. Tobacco’s various smoking products increased significantly during and after World War I but has been shown to be one of the leading causes of death around the world according to the World Health Organization. Thought to increase creativity and reduce hunger, coca is the central ingredient in producing cocaine. Native to the Andes, coca was chewed as part of a ritual in the Inca religion and was adopted as such by Spanish settlers in the New World. Its most famous adaptation was in the creation of Coca-Cola developed in the 1880s by an Atlanta pharmacist as a substitution for alcohol during Prohibition in the United States. Like the soft drink, cocaine has spread around the globe and is one of the most used illegally traded drugs.

Advertisement

Animals

The Columbian Exchange facilitated the transfer of all of the major domesticated animals from the Old World to the Americas: cattle, horses, sheep, goats, and pigs. The few domesticated species in Pre-Columbian America included the dog and the alpaca. The alpaca was limited in its use as it could not be ridden for transportation and could not carry loads greater than c. 35 kg (75 pounds). However, its fur could be used for making cloth. The largest animal present in the Americas was the bison, but it resisted domestication.

The newly introduced animals upset the ecological balance as they ate & destroyed much of the native plants.

The Spanish allowed imported domesticated herds to roam freely over the plentiful supply of lands upon which the animals thrived. Additionally, the Americas contained no natural predators to the new animals. However, these newly introduced animals upset the ecological balance as they ate and destroyed much of the native plants. Three domesticated European animals had an immediate effect: cattle, horses, and pigs. By 1565 cattle ranching spread from the Caribbean to Mexico and Florida. Along with cattle, the Spanish brought the metal plow. This instrument, hitched to cattle, permitted the Europeans to expand the size of their agricultural enterprises. More planted land produced more food and consequently increased the population size and extended life expectancy. Furthermore, cattle provided a stable source of protein in the form of meat and dairy products.

The horse allowed Europeans to travel greater distances into the interior of the continents. The horse also provided greater speed and height advantages in conflicts with the indigenous peoples and frightened the natives with their appearance. Unable to contain the proliferation of reproduction, the horse spread quickly across the Americas. In time the native peoples would adopt and adapt the horse for travel and warfare.

Advertisement

On his second voyage to the Americas in 1493, Columbus brought pigs. Unusually rugged in surviving the ocean voyage, the pig provided the Spanish with an additional source of food. Pigs that escaped into the wild became the ancestors of today’s feral pig population and provided an opportunity for hunting by later explorers and colonists. During Hernando de Soto’s expedition to La Florida (1539-1542), the pig was introduced to North America.

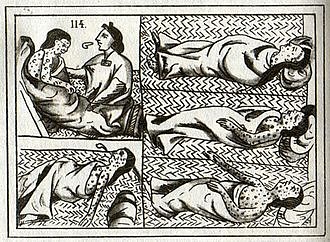

Diseases

The most devastating component of the Columbian exchange was the transfer of Old World diseases to the Americas. Among the lethal germs were smallpox, measles, mumps, whooping cough, chickenpox, typhus, and influenza. The later Transatlantic Slave Trade introduced hepatitis B, malaria, and yellow fever to this deadly disease cocktail. Native populations were decimated by disease outbreaks which allowed the Spanish, and later Europeans, to conquer the indigenous populations more easily.

Most infectious diseases in history have been passed from herds of domesticated animals into the human population in a process known as zoonosis. Beginning after 8,000 BCE, these lethal germs entered Europe, first as occasional outbreaks and then becoming endemics, especially as population density increased. As Europeans lived with domesticated animals, including animals residing in houses, for thousands of years, the prolonged and repeated exposure to those germs allowed the Europeans to develop natural immunities. This, however, did not apply to the indigenous populations in the Americas. Having been cut off from exposure to diseases after the last Ice Age, the native peoples lost any acquired immunities. Additionally, the indigenous population of the Americas had fewer domesticated animals from which diseases might emerge and transfer.

The first disease that made its appearance in the New World was influenza in 1506 followed by smallpox in 1519. Indigenous peoples would begin to sicken and die in extremely high numbers so much so that by 1650 it has been estimated that 90% of the native populations perished. Disease was the most effective ally of the Spanish conquistadors either preceding or accompanying them in their conquests across the Caribbean and the Americas. Hernan Cortés, in August 1519, successfully conquered the largest city in the Americas, Tenochtitlan, after a 75-day siege in which a few hundred conquistadors defeated a native army numbering in the thousands. Disease, warfare, and starvation weakened the abilities of the Aztecs to resist. Cortés’ conquest of the Aztecs ultimately left only about 2 million people of the roughly 11-25 million who existed when the Spanish first arrived in Mexico. Disease also accompanied Francisco Pizzaro when he conquered the Inca in Peru in the early 1530s.

The disease exchange occurred in both directions. Syphilis crossed the Atlantic Ocean back to Europe by some of Columbus’ sailors who had engaged in sexual relations with native women in the Caribbean. A few of those sailors joined the army of Charles VIII of France (r. 1483-1498) when he invaded Italy in 1494-95. The first recorded case of syphilis was reported in Naples in 1495. Recently historians have offered an alternative theory about the introduction of syphilis into Europe. It has been suggested that the disease already existed in Europe prior to the 15th century but was misdiagnosed and thought to be other diseases such as leprosy because the symptoms –pain, rashes, genital ulcers – were similar. Left untreated, syphilis causes death amongst its sufferers.

Consequences

Often referred to as one of the most pivotal events in world history, the Columbian exchange altered life on 3 separate continents. The new plants and animals brought to the Americas and the new plants brought back to Europe transformed farming and human diets. From the 16th century onward, farmers enjoyed a wider variety of plants and animals to choose from to earn a living and expand their prospects for wealth. The new crops on all 3 continents allowed farmers to plant in soils that were previously unusable thus producing higher yields and ending an ongoing history of food insecurity.

To meet the growing labor demands, especially on the expanding cash crop plantations, the Europeans turned to Africa. The Transatlantic Slave Trade represented the largest forced migration of people in human history with the transfer of 12-20 million Africans to the Americas between the 16th to 19th centuries. The result of the various exchanges became known as the triangular trade in which the Americas supplied the Old World with raw materials, Europe transformed those raw materials into finished goods which were traded to Africa and the Americas, while Africa supplied slaves to fulfill labor needs in the New World.

The transfer of domesticated animals to the New World would, along with the transfer of plants, alter human diets, provide new forms of transportation and inaugurate a new form of warfare between peoples for centuries to come. By the 1560s, the islands in the Caribbean were largely depopulated due to lethal, infectious diseases. Not only did whole civilizations collapse due to sickness, another 20% of native peoples died from famine resulting from the collapse of the local farming sector.

Scholarship on the Columbian exchange has expanded to include additional items transferred across the ocean in the centuries after Columbus. Nunn and Qian describe how rubber, found in trees and vines in Central and South America as well as West-Central Africa, was initially used by Africans primarily as an adhesive and Native Americans for boots, tents, and containers. After 1770, the use of rubber increased significantly with the discovery of vulcanization, which created a more stable compound that could be used as electrical insulation along with increased production of tires for bicycles, automobiles, and motorcycles. Rubber production exacted a terrible toll on Central Africa during the period of European colonization.

Other aspects of the Columbian exchange include economic, religious, and cultural transformations. The tremendous amounts of silver which flowed from the mines in South America back to Spain altered the European economy. The new wealth led to better lives for many Europeans and an increased population. The increased circulation of silver permitted the Catholic Church to underwrite a response to the challenges posed by the Protestant Reformation as well as spread Catholicism amongst the natives in the Americas. More detailed maps of lands and oceans, greater circulation of news flowing from the New World assisted by the new printing press, more effective navigational devices such as the compass, and astronomical discoveries helped launch a golden age in literature and art. The Columbian exchange, which started out as the introduction of new plants, animals, and diseases into different cultures, ultimately took on greater significance in the profound cultural, colonial, economic, nationalist, and labor consequences.

Amerigo Vespucci: Italian explorer who named America

Amerigo Vespucci was a 16th century navigator, after whom the American continents are named.

Amerigo Vespucci, the 16th-century explorer America is named after. (Image credit: Getty/ traveler1116)

- Early life

- First voyage

- 1501 voyage and South America

- Later voyages

- Naming of America

- Additional resources

- Bibliography

Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci is best known for his namesake: the continents of North and South America. But why were these continents named after him, especially since his voyages happened after Christopher Columbus arrived on the continent, in 1492?

Vespucci was the first person to recognize North and South America as distinct continents that were previously unknown to Europeans, Asians and Africans, according to Avihu Zakai (“Exile and Kingdom: History and Apocalypse in the Puritan Migration to America (opens in new tab) “, Cambridge University Press, 2002). Prior to Vespucci’s discovery, explorers, including Columbus, had assumed that the New World was part of Asia. Vespucci made his discovery while sailing near the tip of South America in 1501, according to The New World Encyclopaedia (opens in new tab) .

Amerigo Vespucci was one of many European explorers during the Age of Exploration, or Age of Discovery, which took place from the mid-1400s to mid-1500s. “The Age of Exploration was prompted by different motivations,” said Erika Cosme (opens in new tab) , administrative coordinator of education and digital services at The Mariner’s Museum and Park (opens in new tab) in Virginia. “In the 15th century, Europe, Asia, and Africa were at the epicenter of a global exchange of goods; also, for Europeans, curiosities of different cultures continued to emerge. This Afro-Eurasian economy created an interwoven connection between India, China, the Middle East, Africa and Europe.”

Spurred by curiosity and economic incentive, explorers traveled distances that were great feats for their day. But what makes the time period so important, said Cosme, was the role it played in “shaping the world that we know today.” Recognizing the Americas was a major part of that understanding.

Early life

Amerigo Vespucci was born on March 9, 1454, in Florence. As a young man, he was fascinated with books and maps, according to the Mariners Museum (opens in new tab) . The Vespuccis were a prominent family and friends with the powerful Medicis, a family who ruled Italy for more than 300 years and were prominent during the Renaissance. After being educated by his uncle, Vespucci himself worked for the Medicis as a banker and later supervisor of their ship-outfitting business, which operated in Seville, Spain. He moved to Spain in 1492, according to Biography.com (opens in new tab)

This business allowed Vespucci to see the great explorers’ ships being prepared and to learn about the business of exploration. Goods like salt from Mali, coffee beans from Ethiopia, spices from India and the Molucca Islands and ginger, silk and tea from China were in high demand, said Cosme, who works in developing The Mariners’ Museum’s extensive Age of Exploration area.

Countries profited off trade and hoped to find riches like gold, silver and gems, Cosme explained . “European leaders saw exploration as a way to expand their empires and increase national glory.”

At the time, explorers were searching for a northwest route to the Indies — the lands and islands of Southeast Asia — which would make trade easier and bring their country wealth, according to Britannica (opens in new tab) . “It would often take years to complete a trip,” said Cosme. “By the mid-15th century, Muslims controlled the majority of the trade routes to Asia. This meant they could charge high prices for incoming and outgoing goods and vessels traveling to and from Europe and Asia. The desire to find ocean routes that were faster, safer, and cheaper stimulated a search to find a better way of getting to these places.”

Vespucci’s business helped outfit one of Columbus’s voyages, and in 1496 Vespucci had the opportunity to talk with the explorer. Both men were fascinated by the works of Marco Polo, who influenced many explorers’ love of seafaring and exploration, said Cosme.

This meeting further encouraged Vespucci’s interest in travel and discovery. Like many explorers of the age, he wanted to gain new knowledge and see the world with his own eyes. “The Age of Exploration coincided with the Renaissance, which lasted from about 1300 to 1600,” said Cosme. “Many people were gaining genuine curiosity about the world. Sciences like astronomy and cartography were surging. People wanted to know more about the geography, people, and cultures outside their own.”

Vespucci’s business was struggling, which made his decision to voyage even simpler. Furthermore, he possessed critical knowledge for seafaring, like cartography and astronomy, which were essential tools for early navigation, said Cosme. Now in his 40s, Vespucci decided to leave business behind and embark on a journey while he still could.

First voyage and letter controversy

On his 1499 voyage to the West Indies, Vespucci is also said to have found the Southern Cross, an event shown here. (Image credit: Getty/ Photos.com)

“Amerigo Vespucci took at least three voyages westward,” said Cosme. There is some controversy among historians about when Vespucci set sail on his first voyage. Many accounts place the sail date in 1499, seven years after Columbus landed in the Bahamas. On the 1499 voyage, Vespucci sailed to the northern part of South America and into the Amazon River. He gave places he saw names like the “Gulf of Ganges,” thinking, as his explorer contemporaries did, that he was in Asia. He also made improvements to celestial navigation techniques. Vespucci predicted Earth’s circumference accurately within 50 miles, according to Springer (opens in new tab) .

But a letter dated in 1497 suggests that the 1499 voyage may have in fact been Vespucci’s second trip, according to Fordham University (opens in new tab) . The letter is written in Vespucci’s voice, though some historians dispute his authorship and the facts of the document, claiming it a forgery. The letter, written to the Gonfalonier of Florence (a high official on the city-state’s supreme executive council), accounts a 1497 expedition to the Bahamas and Central America. If the accounts of this letter are true, then Vespucci reached the mainland of the Americas a few months before John Cabot and more than a year before Columbus.

1501 voyage and recognition of South America

On May 14, 1501, Vespucci set sail to the New World under the Portuguese flag on what would be his most successful voyage, according to Edward Shaw (“Discoverers and Explorers (opens in new tab) ,” Weitsuechtig, 1900.)

Vespucci’s ships traveled along the South American coast down to Patagonia, according to The New World Encyclopaedia (opens in new tab) . Along the way, he encountered the rivers Rio de Janeiro and Rio de la Plata. During this voyage, Vespucci came to suspect that he was looking at a continent entirely different from Asia.

“Vespucci was both familiar with and fascinated by the accounts of Marco Polo and his time in Asia. The book by Polo gave great detail on the geography, people, and rich opportunities of the continent. Based on this information, Vespucci could make assumptions about the land they were exploring,” Cosme said.

“For starters, Vespucci noticed that the sky which they sailed under had different constellations that were not visible in Europe,” Cosme said. “He also took note of the coastlines they traveled, recording their distance and length of time traveled. Vespucci, again a very skilled cartographer and astronomer, carefully studied and pondered over all of his information.

“He found that the areas and land masses they had explored were actually larger and different than previous accounts of Asia’s descriptions. This led him to the conclusion that what they had explored was indeed an entirely new continent.”

He verified his suspicion when sailing south to within 400 miles of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost tip of South America, according to an article by Wired. This confirmed that he was encountering a new continent that extended far further south than anyone had guessed.

While on this voyage, Vespucci wrote letters to a friend in Europe describing his travels and identifying the New World as a separate continent from Asia. These letters also chronicle his encounters with the indigenous people and describe their culture. Vespucci described the natives’ religious practices and beliefs, their diet, marriage habits, and, most appealingly to readers, their sexual and childbirth practices. These letters were published in several languages and sold well (better than Columbus’ letters, according to Stanford University) across Europe. This pleased Vespucci who, who recorded his adventures to better leave “some fame behind me after I die.”

Later voyages and other accomplishments

Vespucci’s later voyages were not as successful as the 1501 expedition, and , according to Britannica (opens in new tab) , scholars are unsure of exactly how many later voyages he embarked upon. In 1503, he sailed to Brazil, but when his fleet failed to make any new discoveries, the ships disbanded. Vespucci pressed on, however, and discovered the island of Bahia and South Georgia before returning to Lisbon ahead of schedule (“The First Four Voyages of Amerigo Vespucci (opens in new tab) ,” Forgotten Books, 2017) .

Vespucci may have gone on two more voyages, in 1505 and 1507, but accounts are unclear. In 1505, he became a naturalized citizen of Spain, and in 1508, he was named a Pilot Major of Spain, according to Frederick J Pohl (“Amerigo Vespucci”, Columbia University Press, 1944). This was a prestigious position that required him to use his considerable navigational skills. Vespucci helped develop and standardize navigational techniques and to select new pilots.

He worked at this post until his death on Feb. 22, 1512. He contracted malaria and died in Spain at nearly 58 years of age. Vespucci is buried in Florence.

The naming of America

Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 map was the first to use the word “America.” Waldseemüller had proposed naming the newly discovered continents after the Italian explorer. (Image credit: Library of Congress.)

Vespucci’s reputation has gone through periods of ridicule, and at times he has been viewed as a schemer who attempted to steal glory from Columbus, according to History.Info (opens in new tab) . But in reality, it wasn’t Vespucci’s ambition that got two continents named after him: it was the work of a German clergyman and amateur cartographer called Martin Waldseemüller.

In 1507, Waldseemüller and some other scholars were working on an introduction to cosmology that would contain large maps, according to the U.S. Library of Congress (opens in new tab) . Waldseemüller proposed that a portion of Brazil that Vespucci had explored be named “America,” a feminized version of Vespucci’s first name. Waldseemüller wrote, “I see no reason why anyone should justly object to calling this part . America, after Amerigo [Vespucci], its discoverer, a man of great ability.”

The name stuck. Waldseemüller’s maps sold thousands of copies across Europe. Some reports suggest, for example the Library of Congress (opens in new tab) , that Waldseemüller had second thoughts about the name America, but it was too late. In 1538, a mapmaker named Gerardus Mercator applied the name “America” to both the northern and southern landmasses of the New World, according to Yale University (opens in new tab) and the continents have been known as such ever since.

Regardless, there is no underestimating the value of Vespucci’s contributions to Europeans. Cosme said, “Amerigo Vespucci used his own knowledge and skill, plus the written knowledge from scholars and explorers before him to uncover a Mundus Novus (Latin for “new world”) to Europeans.”

Additional resources

To learn more about the Waldseemüller map from which America would get its name, check out this article from the Library of Congress. (opens in new tab) To learn more about Vespucci himself, read this piece from The Mar (opens in new tab) iners’ Museum. Or try this article from PBS World Explorers (opens in new tab) .

Source https://www.worldhistory.org/Columbian_Exchange/

Source https://www.livescience.com/42510-amerigo-vespucci.html

Source