Coming to America: Who Was First?

Coming to America: Who Was First?

Columbus gets the credit for being the first to land on these shores. Does he deserve it?

Columbus Competitors: The Theories

Was Christopher Columbus first? A host of competing theories say no. Here are a few of the more prominent ones:

Sixth Century — Irish Monks: This “theory” is actually more of a legend. A sixth-century Irish monk named Saint Brendan supposedly sailed to North America on a currach — a wood-framed boat covered with animal skin. His alleged journey is detailed in the ancient annals of Ireland. Brendan was a real historical figure who traveled extensively in Europe. But there is no evidence that he ever made landfall in North America.

In 1976, writer Tim Severin set out to prove that such a journey was possible. Severin built the Brendan, an exact replica of a sixth-century currach, and sailed along a route described by the traveling monks. He eventually landed in Canada.

10th Century — The Vikings: The Vikings’ early expeditions to North America are well documented and accepted as historical fact by most scholars. Around the year 1000 A.D., the Viking explorer Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red, sailed to a place he called “Vinland,” in what is now the Canadian province of Newfoundland. Erikson and his crew didn’t stay long — only a few years — before returning to Greenland. Relations with native North Americans were described as hostile.

This much had long been known from the Icelandic sagas. But until 1960, there was no proof of Erikson’s American sojourns. That year, Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad, unearthed an ancient Norse settlement. During the next seven years, the Ingstads and an international team of archaeologists exposed the foundations of eight separate buildings. In 1969, Congress designated Oct. 9 as “Leif Erikson Day.”

15th Century — The Chinese: This theory is espoused by a small group of scholars and amateur historians led by Gavin Menzies, a retired British Naval officer. It asserts that a Muslim-Chinese eunuch-mariner from the Ming Dynasty discovered America — 71 years before Columbus. Zheng He was a real historical figure, who commanded a huge armada of wooden sailing vessels in the early 15th century. He explored Southeast Asia, India and the east coast of Africa using navigational techniques that were, at the time, cutting edge.

But Menzies, in his best-selling 2003 book, 1421: The Year China Discovered America, asserts that Zheng He sailed to the east coast of the United States, and may have established settlements in South America. Menzies based his theory on evidence from old shipwrecks, Chinese and European maps, and accounts written by navigators of the time. Menzies’ scholarship, though, has been called into question. Many of his claims are presented “without a shred of proof,” says historian Robert Finlay, writing in the Journal of World History. Indeed, most historians say the “China first” theory is full of holes.

Who discovered America?

For most of us, the answer to that question is straightforward: Christopher Columbus. That’s what we were taught in school and that is why we celebrate Columbus Day. Yet it is far from clear-cut.

There are alternative theories about who got here first — some well-documented, others much more flimsy in their scholarship. Author Russell Freedom explores the various contenders for the title of “first” in his new book, Who Was First? Discovering the Americas. He shares his insights with NPR.

When you started this project, were you like the rest of us? Did you believe that Christopher Columbus discovered America and that was it, end of story?

I was vaguely aware of the Vikings. But really, what incited my interest was a book called 1421: The Year China Discovered America. That book has been largely debunked, but what is clear is that there have been successive waves of immigration to the Western Hemisphere from outside. Where they came from and when they arrived and how they got here — that’s all still speculative.

Tell me about the Irish Monks who supposedly predated even the Vikings.

That falls into the realm of legend. But it’s possible that they came across the North Sea, to what is now Newfoundland, before the Vikings. No one knows for sure.

And the Vikings?

That is well established. I visited the archeological site at the northern tip of Newfoundland. There is no question about it. It has been definitely determined that the Vikings were there for about 10 years — specifically, Leif Erikson and his extended family.

Is there any physical evidence that remains today?

Yes, the remains of their houses, of their settlement. There was an archeological dig that lasted six or seven years, and then they reconstructed the settlement about 100 yards away.

What did Leif Erikson make of this New World?

It was full of wonderful resources: timber and grapes. Coming from Greenland, as he did, which had no timber or grapes to make wine, these were two priceless discoveries. That’s why the Vikings called it “Vinland” or Wine Land.

So if it was so wonderful, why didn’t the Vikings stay longer?

The Indians didn’t want them to stay. The first encounter was when the Vikings came across 10 Indians taking naps under their overturned canoes — and the Vikings killed them. That did not set up a very good mutual relationship. There were some attempts at trading, but the Vikings felt quite menaced and outnumbered, and the Indians did not appreciate their presence. The Vikings did return to North America, but only for trading. They never settled again.

What about the “China first” theory? Is there any evidence to support the notion that Chinese mariners set foot in America before Columbus?

There is credible evidence that a Chinese fleet went as far as the coast of Africa, in present-day Kenya. It was the largest maritime fleet in the world, under the command of Zheng He, a favorite of the emperor. Whether the fleet went around the horn of Africa and then across the Atlantic is speculative. The theory has been widely shot down by experts in the field. There is no real evidence. The author uses a grab bag of evidence, some of it is suggestive and some of it is ridiculous.

So if Columbus wasn’t first, why does he get all of the credit?

He opened up America to Europe, which was the expansionist power at the time. He was the one who made it possible for them to conquer the Western Hemisphere — and to bring with them the diseases that apparently wiped out 90 percent of the population. He wasn’t the first (and neither were the Vikings) — that is a very Euro-centric view. There were millions of people here already, and so their ancestors must have been the first.

What did you find most surprising in researching this book?

For one thing, the longevity of settlement of the Western Hemisphere — 20,000 years, at least. I don’t think it’s silly, this quest for answers of who got here first. You always want to know what happened before you. It’ a human instinct to know where you came from and what proceeded you. How did they get here? Who were they? The fact that we don’t know for sure makes it quite fascinating.

by Russell Freedman

Hardcover, 88 pages |

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

Excerpt: ‘Who Was First?’

Read an excerpt from Who Was First? by Russell Freedman:

Before Columbus

For a long time, most people believed that Christopher Columbus was the first explorer to “discover” America—the first to make a successful round-trip voyage across the Atlantic. But in recent years, as new evidence came to light, our understanding of history has changed. We know now that Columbus was among the last explorers to reach the Americas, not the first.

Five hundred years before Columbus, a daring band of Vikings led by Leif Eriksson set foot in North America and established a settlement. And long before that, some scholars say, the Americas seem to have been visited by seafaring travelers from China, and possibly by visitors from Africa and even Ice Age Europe.

A popular legend suggests an additional event: According to an ancient manuscript, a band of Irish monks led by Saint Brendan sailed an ox-hide boat westward in the sixth century in search of new lands. After seven years they returned home and reported that they had discovered a land covered with luxuriant vegetation, believed by some people today to have been Newfoundland.

All along, of course, the two continents we now call North and South America had already been “discovered.” Before European explorers arrived, the Americas were home to tens of millions of native peoples. While those Native American groups differed greatly from one another, they all performed rituals and ceremonies, songs and dances, that brought back to mind and heart memories of the ancestors who had come before them and given them their place on Earth.

Who were the ancestors of those Native Americans? Where did they come from, when did they arrive in the Americas, and how did they make their epic journeys?

As we dig deeper and deeper into the past, we find that the Americas have always been lands of immigrants, lands that have been “discovered” time and again by different peoples coming from different parts of the world over the course of countless generations—going far back to the prehistoric past, when a band of Stone Age hunters first set foot in what truly was an unexplored New World.

1. Admiral of the Ocean Sea

Christopher Columbus was having trouble with his crew. His fleet of three small sailing ships had left the Canary Islands nearly three weeks earlier, heading west across the uncharted Ocean Sea, as the Atlantic was known. He had expected to reach China or Japan by now, but there was still no sign of land.

None of the sailors had ever been so long away from the sight of land, and as the days passed, they grew increasingly restless and fearful. The Ocean Sea was known also as the Sea of Darkness. Hideous monsters were said to lurk beneath the waves—venomous sea serpents and giant crabs that could rise up from the deep and crush a ship along with its crew. And if the Earth was flat, as many of the men believed, then they might fall off the edge of the world and plunge into that fiery abyss where the sun sets in the west. What’s more, Columbus was a foreigner—a red-headed Italian commanding a crew of tough seafaring Spaniards—and that meant he couldn’t be trusted.

Finally, the men demanded that Columbus turn back and head for home. When he refused, some of the sailors whispered together of mutiny. They wanted to kill the admiral by throwing him overboard. But, for the moment, the crisis passed. Columbus managed to calm his men and persuade them to be patient a while longer.

“I am having serious trouble with the crew . . . complaining that they will never be able to return home,” he wrote in his journal. “They have said that it is insanity and suicidal on their part to risk their lives following the madness of a foreigner. . . . I am told by a few trusted men (and these are few in number!) that if I persist in going onward, the best course of action will be to throw me into the sea some night.”

All along, Columbus had been keeping two sets of logs. One, which he kept secretly and showed to no one, was accurate, recording the distance really sailed each day. The other log, which he showed to his crew, hoping to reassure them that they were nowhere near the edge of the world, deliberately underestimated the miles they had covered since leaving Spain.

They sailed on for another two weeks and still saw nothing. There were more rumblings of protest and complaint from the crew. The men seemed willing to endure no more. On October 10, Columbus announced that he would give a fine silk coat to the man who first sighted land. The sailors greeted that offer with glum silence. What good was a silk coat in the middle of the Sea of Darkness?

Later that day, Columbus spotted a flock of birds flying toward the southwest—a sign that land was close. He ordered his ships to follow the birds.

The next night, the moon rose in the east shortly before midnight. About two hours later, at two A.M. on October 12, a sailor on one of Columbus’s ships, the Pinta, saw a white stretch of beach, shouted, “Land! Land!” and fired a cannon. At dawn, the three ships dropped anchor in the calm, blue waters just offshore. They had arrived at an island in what we now call the Bahamas.

Excited crew members crowded the decks. People were standing on the beach, waiting to greet them. The natives had no weapons other than wooden fishing spears, and they were practically naked. Who were these people? And what place was this?

Columbus supposed that his fleet had landed on one of the many islands that Marco Polo had reported lay just off the coast of Asia. They must have reached the Indies, he thought—islands reputedly near India and known today as the East Indies. So he decided that those people on the beach must be “Indians,” the name by which they have been known ever since. China and Japan, he believed, lay a bit farther to the north.

Though Christopher Columbus was an Italian born in Genoa, he had lived for years in Portugal, where he worked as a bookseller, a mapmaker, and a sailor. He had sailed on Portuguese voyages as far as Iceland in the North Atlantic, and down the coast of Africa in the South Atlantic. During his days at sea, he read books on history, geography, and travel.

Like most educated people at the time, Columbus believed that the Earth was round—not flat, as some ignorant folks still insisted. The Ocean Sea was seen as a great expanse of water surrounding the land mass of Eurasia and Africa, which stretched from Europe in the west to China and Japan in the far distant east. If a ship left the coast of Europe, sailed west toward the setting sun, and circled the globe, it would reach the shores of Asia—or so Columbus thought.

In the past, European explorers and traders had taken the overland route to the Far East, with its precious silks and spices. They traveled for months by horse and camel along the Silk Road, an ancient caravan trail that crossed deserts and climbed dizzying mountain peaks. Marco Polo had followed the Silk Road on his famous journey to China two centuries earlier. But recently, this land route to Asia, controlled in part by the Turks, had been closed to Europeans. And in any case, Columbus was convinced that he could find an easier and faster route to Asia by sailing west.

There were plenty of stories circulating in those years about the possibility of sailing directly from Europe to Asia, an idea first considered by the ancient Greeks. Columbus owned a book called Imago Mundi, or Image of the World, by a French scholar, Pierre d’Ailly, who argued that the Ocean Sea wasn’t as wide as it seemed and that a ship driven by favorable winds could cross it in a few days. Next to that passage in the margin of the book, Columbus had written: “There is no reason to think that the ocean covers half the earth.”

In 1484, he proposed his bold scheme of sailing west to China to King John II of Portugal, a monarch who had paid much attention to the discovery of new lands. Portugal was Europe’s leading maritime power. Portuguese explorers in search of slaves, ivory, and gold had already discovered rich kingdoms and colossal rivers in western Africa and would soon reach the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip. From there, they would be able to sail across the Indian Ocean to the famed Spice Islands of southeast Asia.

King John listened to what Columbus had to say, then submitted the Italian sailor’s plan to a committee of mapmakers, astronomers, and geographers. The distinguished experts declared that Asia must be much farther away than Columbus thought. They said that no expedition could be fitted out with enough food and water to sail across such an enormous expanse of sea.

Rejected by the Portuguese king, Columbus decided to approach King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, a country he had never before visited. Well-connected friends gave him letters of introduction to the inner circle of the Spanish royal court. Ferdinand and Isabella seemed curious about the route to Asia that Columbus proposed. Like King John, they too appointed a committee of inquiry to consider the matter, but those experts came to the same negative conclusion: Columbus’s claim about the distance to China and the ease of sailing there could not possibly be true.

Columbus persisted. He talked at length to members of the Spanish court and convinced some of them, but Ferdinand and Isabella twice rejected his appeal for ships. Finally, angry and impatient after six discouraging years in Spain, he threatened to seek support from the king of France. Columbus actually set out for France, riding a mule down a dusty Spanish road.

With that, royal advisors persuaded Ferdinand and Isabella to change their minds. If another king sponsored Columbus, and his expedition turned out to be a success, then the Spanish monarchs would be embarrassed. They would be criticized in Spain. Let Columbus risk his life, the advisors said. Let him seek out “the grandeurs and secrets of the universe.” If he succeeded, Spain would win much glory and would overcome the Portuguese lead in the race to exploit the riches of Asia.

And so Ferdinand and Isabella decided to take a chance. They dispatched a messenger to intercept Columbus on the road and bring him back to court. They were ready to grant him a hereditary title, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, and the right to a tenth of any riches—pearls, gold, silver, silks, spices—that he brought back from his voyage. And they agreed to supply two ships for his expedition. Columbus himself raised the money to hire a third ship.

A half hour before sunrise on August 3, 1492, the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa María sailed from the port of Palos, Spain, carrying some ninety crew members in all. They were small, lightweight ships called caravels, swift and maneuverable, each with three masts, their white sails with big red crosses billowing before the wind. They had on board food that would last—salted cod, bacon, and biscuits, along with flour, wine, olive oil, and plenty of water, enough for a year. In his small cabin, Columbus kept several hourglasses to mark the passage of time, a compass, and an astrolabe, an instrument for calculating latitude by observing the movement of the sun.

The little fleet stopped for repairs at La Gomera in the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession off the coast of Morocco. On September 6, after praying at the parish church of San Sebastian (which still looks out over the ocean today), Columbus and his three ships set sail again, heading due west, moving now through the unknown waters of the Ocean Sea. Five weeks later, on October 12, his worried crew finally sighted land.

Columbus called the place where they landed San Salvador—the first of many Caribbean islands that he would name. The natives who greeted him called their island Guanahani. They themselves were a people known as the Tainos, the largest group of natives inhabiting the islands of what we today call the West Indies.

Columbus tells us a few things about these now-extinct people. He was impressed by their good looks and apparent robust health. “They are very well-built people, with handsome bodies and very fine faces,” he wrote in his log. “Their eyes are large and very pretty. . . . These are tall people and their legs, with no exceptions, are quite straight, and none of them has a paunch.” Many of the Tainos had painted their faces or their whole bodies black or white or red. And as Columbus and his men noticed right away, some of them wore gold earrings and nose rings. They offered gifts to the European visitors—parrots, wooden javelins, and balls of cotton thread.

From San Salvador, Columbus sailed on to several more islands, still believing that he was close to Japan “because all my globes and world maps seem to indicate that the island of Japan is in this vicinity.” He stopped at Cuba and at Hispaniola (the island that today contains Haiti and the Dominican Republic). And he wrote enthusiastically in his journal of the lush tropical beauty of the islands, the sweet singing of birds “that might make a man wish never to leave here,” and the hospitality of the people: “They gave my men bread and fish and whatever they had.” And later, “They brought us all they had in this world, knowing what I wanted, and they did it so generously and willingly that it was wonderful.”

The Tainos lived in large, airy wooden houses with palm roofs. They slept in cotton hammocks, sat on wooden chairs carved in elaborate animal shapes, and kept small barkless dogs and tame birds as pets. They were skilled farmers, fishermen, and boat builders who traveled from island to island in long, brightly painted canoes carved from tree trunks, each of which carried as many as 150 people.

They told Columbus that they called themselves Tainos, a word meaning “good,” to distinguish themselves from the “bad” Caribs, their fierce, warlike neighbors who raided Taino villages, carried off their girls as brides, and, the Tainos insisted, ate human flesh. To fend off Carib attacks, the Tainos painted themselves red and fought back with clubs, bows and arrows, and spears propelled by throwing sticks.

The Tainos themselves were not warlike, Columbus reported to his monarchs: “They are an affectionate people, free from avarice and agreeable to everything. I certify to Your Highnesses that in all the world I do not believe there is a better people or a better country. They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the softest and gentlest voices in the world and are always smiling.”

A village chief gave Columbus a mask with golden eyes and large ears of gold. And the Spaniards were already aware that many of the Tainos wore gold jewelry. They kept asking where the gold came from. After much searching, they found a river on the island of Hispaniola where “the sand was full of gold, and in such quantity, that it is wonderful. . . . I named this El Rio del Oro” (The River of Gold).

Columbus built a small fort nearby and left thirty-nine men behind to collect gold samples and await the next Spanish expedition. Still believing that he had discovered unknown islands near the shores of Asia, he sailed back to Spain with some gold from Hispaniola and with ten Indians he had kidnapped so he could train them as interpreters and exhibit them at the royal court. One of the Indians died at sea.

He returned to a triumphant welcome. It was said that when Ferdinand and Isabella received him at their court in Barcelona, “there were tears in the royal eyes.” They greeted Columbus as a hero, inviting him to ride with them in royal processions. A second voyage was planned. This time, the monarchs gave Columbus seventeen ships, about fifteen hundred men, and a few women to colonize the islands. He was instructed to continue his explorations, establish gold mines, install settlers, develop trade with the Indians, and convert them to Christianity.

Columbus returned to Hispaniola in the fall of 1493. He hoped to find huge amounts of gold on the island. But the mines yielded much less gold than expected, and the European crops planted by the settlers wilted in the tropical climate. Some settlers began to lord it over the Indians, stealing their possessions, abducting their wives, and seizing captives to be shipped to Spain and sold as slaves. Thousands of Tainos fled to the mountains to escape capture. Others, vowing to avenge themselves, attacked any Spaniards they found in small groups and set fire to their huts.

While Columbus was a courageous and enterprising mariner, he proved to be a poor governor, unable to control the greed of his followers. In 1496, he was called back to Spain to answer complaints about his management of the colony. When he appeared at court before Ferdinand and Isabella, he found the king and queen were still willing to support his explorations. Columbus gave them a “good sample of gold . . . and many masks, with eyes and ears of gold, and many parrots.” He also presented to the monarchs “Diego,” the brother of a Taino chief, who was wearing a heavy gold collar. These hints that more gold might be forthcoming encouraged Ferdinand and Isabella to send Columbus back to the Indies, this time with eight ships.

When he returned to Hispaniola on his third voyage in 1498, he found the island in turmoil, torn by rivalries and disagreements among the settlers. Many colonists, unable to make a living from the gold mines or by farming, were clamoring to return to Spain. Others, rivals of Columbus who wanted to gain control of the colony, rebelled against his rule. When word of the conflict reached Spain, the king and queen sent an emissary, Francisco de Bobadilla, to investigate the uprising and take charge of the government.

Columbus, it seems, made the mistake of arguing with the royal emissary and challenging his credentials. He was promptly arrested and with his two brothers was shipped back to Spain to face charges of wrongdoing. “Bobadilla sent me here in chains,” he wrote to Ferdinand and Isabella when he landed in Spain. “I swear that I do not know, nor can I think why.” Though Columbus was quickly pardoned by the Spanish monarchs, who felt he had been treated too harshly, he was stripped of his right to govern the islands he had discovered, and he lost his title as Admiral of the Ocean Sea.

Even so, he was allowed to make one more voyage, sailing across the Caribbean and exploring the coast of Central America. This final expedition was cursed by bad luck. Two of Columbus’s ships became so infested with termites, they sank. When he headed back to Spain, he had to beach his remaining ships at St. Ann’s Bay in Jamaica, where he was marooned for a year before being rescued in the fall of 1504. He returned to Spain an ill and disappointed man.

Spanish colonists, meanwhile, had been settling in Hispaniola, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and other islands in the West Indies. The local Indians were put to work as forced laborers in the goldfields or on Spanish ranches. Indians who resisted were killed, sometimes with terrible brutality, or were shipped to Spain to be sold as slaves. Spanish missionaries denounced this mistreatment, but with little effect. “I have seen the greatest cruelty and inhumanity practiced on these gentle and peace-loving [native peoples],” Father Bartolomé de Las Casas would say a half century later, “without any reason except for insatiable greed, thirst, and hunger for gold.”

As the number of Spanish colonists increased, the native population of the West Indies quickly declined. Tens of thousands of native people were worked to death or died of smallpox, measles, and other European diseases to which they had no immunity. As the Tainos died off, the colonists brought in black slaves from Africa to labor on ranches and in the spreading sugar-cane fields.

Within fifty years, the Tainos had ceased to exist as a distinct race of people. A few Taino words survive today in Spanish and even in English, including hammock, canoe, hurricane, savannah, barbecue, and cannibal.

Columbus died in a Spanish monastery on May 20, 1506, at the age of fifty-seven, still believing that he had found a new route to Asia, and that China and Japan lay just beyond the islands he had explored. By then, other explorers were following the sea route pioneered by the Admiral of the Ocean Sea, and Europeans were already speaking of Columbus’s discoveries as a “New World.”

The first map of the world to show these newly discovered lands across the Ocean Sea appeared in 1507, a year after Christopher Columbus’s death. The mapmaker, Martin Waldseemüller, named the New World “America,” after the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, who had explored the coastline of South America and was the first to realize that it was a separate continent, not part of Asia.

Columbus wasn’t the first explorer to “discover” America. His voyages were significant because they were the first to become widely known in Europe. They opened a pathway from the Old World to the New, paving the way for the European conquest and colonization of the Americas, changing life forever on both sides of the Atlantic.

Excerpted from Who Was First? Copyright © 2007 by Russell Freedman.

South America for First-Timers – Which Region is Right for You?

We’ve divided South America into regions and summarised their best attributes: finding your ideal first-time destination just got easier!

Maybe you’ve dreamt of South American adventures your entire life or, maybe, the continent has just entered into your travel-radar. Whatever the case may be, planning a first-time visit to South America – an enormous and enormously varied one at that, is an exciting endeavour but it can also be just a wee bit daunting. Where does one even start? Don’t worry—this guide to South America for first-timers will help you get planning.

The breathtaking Cusco, Peru. Credit: Shutterstock

Most first-time travellers to South America really do have the issue of not knowing where to start although, when asked, can usually fire off an impressive list of highlights they wish to include on their itinerary. Everyone has a South American dream, be it to hike the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, stand under the overpowering cascades at Iguazu Falls or meet all the stunning creatures of the Galapagos Islands and the Pantanal.

The first main point is to note that all of these ‘highlights’, the most famous of places in South America, can be easily reached from any major city in the continent and can all be included into one itinerary. Getting around in South America is easy and convenient and including various countries in a single trip is something most people do, whether they love the buzz of cities, wildlife, photography, culture or hiking in the great outdoors.

Los Glaciares National Park. Credit: Shutterstock

Having said all this, it’s important to note that every country is South America offers a multi-coveted travel experience. All of them boast exceptional cities, excellent culture and cuisine, wonderful wilderness and a fair share of wildlife. So choosing the ideal first-time destination may be better achieved when talking about regions, instead.

Divide and Conquer – Choosing Your Ideal Itinerary by Region

Generally speaking, it’s useful to separate South America into three distinct regions, namely the high-altitude Andean region in the centre, the wild southern region (Patagonia, mostly) and the northern tropical, Caribbean region.

South America is also a huge place, so it makes logical sense to start with just one region to save yourself time.

No matter what time of year you choose to visit South America for the very first time, there will be one region that will be at its prime and if you can’t decide where to go first then why not let the climate decide?

- June – September: Dry days and moderate temperatures in the mountainous centre during the northern summer, ideal for hiking and travelling through the Central Andesc

- October -March/April: Moderate temps that are ideal for outdoor adventures in the far south, best for active visits to Patagonia

- November – April: Manageable heat and humidity and less rain in the northern, Caribbean region

Many of these ‘ideal months’ will certainly overlap in various regions due mostly to the fact that some countries – like Argentina and Brazil – are simply huge. This is what makes multi-country itineraries so popular here.

Here’s a look at the three regions in more details.

1. Andean Region – Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador

Best For: cultural experiences, historical sites and close-up adventures across high peaks

The three countries that lie primarily across the Central Andes are the three with the highest percentage of indigenous populations. For this reason, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador are all renowned for offering fantastic cultural experiences and are beloved by those looking for immersive experiences that include, nature, culture, cuisine and history. Here is where you’ll find the most famous archaeological sites and where you can enjoy fantastic road trips that allow you to actually cross those majestic mountains by road, not just admire them from viewpoints.

The beautiful Ecuadorian Andes

Of these three Andean beauties, Peru is the most popular choice (thanks, Machu Picchu!) and Ecuador the lesser-known, ideal for those who want to stray off the Gringo Trail just a tad. All three boast amazing highlights – from Lake Titicaca and Salar Uyuni of Bolivia to the Galapagos and fabulous hot springs of the Ecuador highlands – and all three offer excellent springboards for adventures in the Amazon Rainforest.

Bolivia is one of the least developed countries in South America and although this can make for exceptional travel experiences outside the standard comfort bubble, it can also pose the biggest logistical challenges for first-timers, which is why private tours in Bolivia are so popular. If you’re ever going to take a tailor-made private tour in South America, take it in Bolivia.

The streets of La Paz, Bolivia. Credit: Shutterstock

2. Southern Region – Argentina, Chile, Uruguay

Best For: Overwhelming wilderness, vibrant modern cities, mestizo culture, spectacular mountains, hiking & outdoor pursuits

European immigration has had a much more prevalent role in the evolution of the southern countries and although indigenous experiences still exist in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, you do have to go a little out of your way to find them. Whilst Brazil may be considered by experts to be the economic powerhouse of South America, it’s in these three southern nations where prosperity is most visible and tangible: here is where you’ll find the best infrastructure, most modern cities and a more European flair, overall.

For this reason, Chile, Argentina and Uruguay are ideal for first-time visitors who want a more ‘sanitized’ introduction to South America and are a little apprehensive about jumping in head-first into the arguably more chaotic Central Andean region. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t include it in your first-ever visit but you may just want to include it later on in your trip, when you’ve acclimatised – literally and figuratively speaking – to South America travel.

Despite all this modernity, however, the southern nations of South America boast incredible wilderness, most notably down in Patagonia where it’s dramatic peaks, glaciers and expansive national parks overflowing with wildlife that tickle the fancy of wilderness lovers. All three of the nations’ capitals, Buenos Aires, Santiago and Montevideo, boast resplendent colonial-era architecture, fabulous culinary delights, a vibrant nightlife and totally captivating vibes. If you’re after a city-escape, primarily, here is where you’ll want to arrive.

The National Congress building in Buenos Aires. Credit: Shutterstock

Although each of the three countries boast their own unique highlights (the Atacama Desert and magnificent fjords in Chile, authentic estancia stays in Uruguay and the startling pampas of Argentina) all three share common bonds: world-class wine-growing regions, famous meat-focused cuisines, mate-drinking, siesta-making and a 300-year-old gaucho-culture that’s even tipped to soon be recognised by UNESCO as an intangible treasure.

The organic vineyards of Mendoza, Argentina

Interestingly enough, Argentina and Chile can be said to boast the most spectacular peaks in the Andes: not just the highest but, in particular, the most picturesque. Yet because this southern stretch of the Andes lacks expansive plateaus, people never settled in high-elevation areas the way they did in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador. This means there’s a distinct lack of roads in Patagonia and most of your sightseeing efforts are centred around hiking from a few key hubs instead, offering a totally different Andean perspective.

Torres del Paine National Park. Credit: Shutterstock.

3. Northern Region – Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela

Best For: Caribbean/Afro cultures, stunning beaches, tropical wilderness, friendly locals, wildlife galore

The friendliest people, the warmest temps, the most tropical wilderness, the best dancers and the most avid party-makers: this is what primarily defines South America’s northern countries. Alongside the eclectic cultural highlights, Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela also boast an impressive array of singular highlights – some of the best in the whole continent.

Brazil has its addictive samba and captivating Rio de Janeiro, its awe-inspiring Iguazu Falls, its famous portion of the Amazon rainforest and its astonishing Pantanal – about the best wildlife-watching tropical destination in the world.

Colombia has its colonial treasure of Cartagena – considered the best-preserved in the continent – as well as a collection of simply stupendous Caribbean islands that make for ideal beachside vacays, especially at the end of a whirlwind first-time tour through the continent.

And Venezuela, although currently suffering through a bout of political instability, is still home to striking Angel Falls, the highest on the planet. Venezuela is the prime destination for wilderness enthusiasts who don’t mind giving up comforts in favour of pristine jungles, cloud-covered mountain plateaus and some of the most unspoiled tropical wilderness in the world. The country may be in turmoil at time of writing and travel here not recommended by most government agencies but keep an eye out on this beauty: when things settle, this will be the next ‘hottest’ destination in South America.

Salto Angel waterfall, Venezuela. Credit: Shutterstock.

Whether it’s your first or tenth time visiting South America, the continent offers a wealth of exciting options, hidden secrets and lesser-known yet equally enchanting treasures.

Need more help deciding where to go?

Then see our vast collection of itinerary ideas and contact us for more personalised advice.

Author: Laura Pattara

“Laura Pattara is a modern nomad who’s been vagabonding around the world, non-stop, for the past 15 years. She’s tour-guided overland trips through South America and Africa, travelled independently through the Middle East and has completed a 6-year motorbike trip from Europe to Australia. What ticks her fancy most? Animal encounters in remote wilderness, authentic experiences off the beaten trail and spectacular Autumn colours in Patagonia.”

Did Paleoamericans Reach South America First?

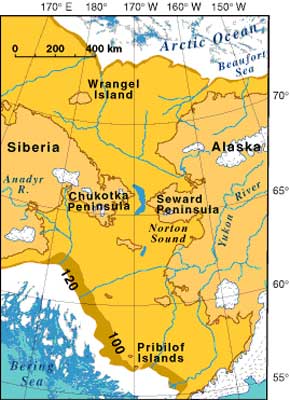

In “ Textbook Story of How Humans Populated America is Biologically Unviable, Study Finds ”, recently published in Ancient Origins, it was noted that DNA studies indicate that people could not have crossed the Beringia land bridge to enter the Americas 13,000 years ago because the “entry route was biologically unviable”. Although this finding by geneticists is surprising, it adds even more mystery to the archaeological evidence that anatomically modern humans were in South America tens of thousands of years before Ice Age people could have crossed a viable land bridge between Alaska and Siberia.

The earliest dates for habitation of the American continent to occur below Canada in South America are highly suggestive that the earliest settlers on the American continents came from Africa before the Ice melted at the Bering Strait and moved northward as the ice melted. An African origin for these people is a good fit because Ocean Currents would have carried migrants from Africa to the Americas, since there were no Ice Age sheets of ice to block passage across the southern Atlantic.

Important Archeological Sites

Dr. Bryan, in Natural History has noted many sites where PaleoAmericans have left us evidence of human habitation, including the pebble tools at Monte Verde in Chile (c.32,000 Before Present), rock paintings at Pedra Furada in Brazil (c.22,000 BP), and mastodon hunting in Venezuela and Colombia (c.13,000 BP). These discoveries have led some researchers to believe that the Americas were first settled from South America.

The main evidence from the ancient Americans are prehistoric tools and rock art, like those found by Dr. Nieda Guidon. Today archaeologists have found sites of human occupation from Canada to Chile that range between 20,000 and 100,000 years old. Guidon, in numerous articles claims that Africans were in Brazil between 65,000-100,000 years ago. Guidon also claims that man was at the Brazilian sites 65,000 years ago. She told the New York Times that her dating of human populations in Brazil 100,000 years ago was based on the presence of ancient fire and tools of human craftsmanship at habitation sites.

Martin and R. G. Klein, after discussing the evidence of mastodon hunting in Venezuela 13,000 years ago, observed that: “The thought that the fossil record of South America is much richer in evidence of early archaeological associations than many believed is indeed provocative. Have the earliest hunters been overlooked in North America? “

Warwick Bray has pointed out that there are numerous sites in North and South America which are over 35,000 years old. A.L. Bryan noted that these sites include, the Old Crow Basin (c.38,000 BC) in Canada; Orogrande Cave (c.36,000 BC) in the United States; and Pedra Furada (c.45,000 BC) in Brazil.

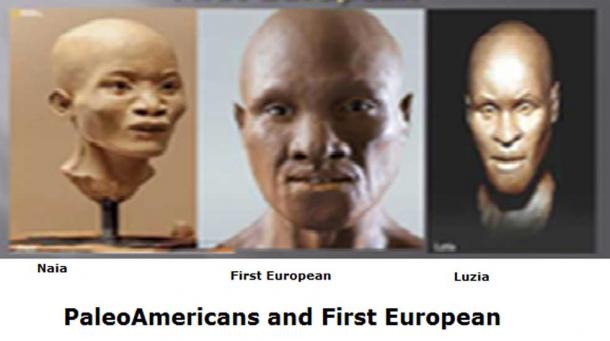

Using craniometric quantitative analysis and multivariate methods, Dr. Neves determined that Paleo Americans were either Australian, African or Melanesians. The research of Neves indicated that the ancient Americans represent two populations, PaleoAmericans who were phenotypically African, Australian or Melanesian and an Asiatic population that appears to have arrived in the Americas after 6000 BC.

Archaeologist have reconstructed the faces of ancient Americans from Brazil and Mexico. These faces are based on the skeletal remains dating back to 12,000BC. The PaleoAmericans resemble the first Europeans.

PaleoAmericans and First European

Researchers working on the prehistoric cultures of these ancient people note that they resemble the Black Variety of humanity, instead of contemporary Native Americans. The Black Variety include the Blacks of Africa, Australia, and the South Pacific.

Dr. Chatters, who found Naia’s skeleton, told Smithsonian Magazine that: “The small number of early American specimens discovered so far have smaller and shorter faces and longer and narrower skulls than later Native Americans, more closely resembling the modern people of Africa, Australia, and the South Pacific. “This has led to speculation that perhaps the first Americans and Native Americans came from different homelands,” Chatters continues, “or migrated from Asia at different stages in their evolution.”

A cast of Luzia’s skull at the National Museum of Natural History. (CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Although Dr. Chatters believes the PaleoAmericans came from Asia, this seems unlikely, because of the Ice sheet that blocked migration from Asia into the Americas. C. Vance Haynes noted that: “If people have been in South America for over 30,000 years, or even 20,000 years, why are there so few sites? [. ]One possible answer is that they were so few in number; another is that South America was somehow initially populated from directions other than north until Clovis appeared”.

The fact that the Beringia land bridge was unviable 15,000 years ago make it unlikely that during the Ice Age man would have been able to walk or to sail from Asia to South America at this time. As a result, these people were probably from Africa, as suggested by Dr. Guidon.

Prehistoric Sea Travel

In summary, the land bridge between Siberia and Alaska was unviable before 13,000 BC. Even though man could not enter the Americas until after 14,000 years ago, man was probably in South America as early 100,000 years ago, according to Dr. Guidon’s research in Brazil.

The first people in the Americas are called PaleoAmericans. The research of Chatters and Neves indicate that the PaleoAmericans were not Asiatic. These researchers claim the PaleoAmericans, “more closely resembl[ed] the modern people of Africa, Australia, and the South Pacific.”

The first Americans probably came to the Americas by sea, due to the unviable land route to the Americas before 13,000 BC. As a result, we must agree with Guidon that man probably traveled from Africa to settle prehistoric America.

The archaeological evidence indicates that PaleoAmericans settled South America before North America, and that these Americans did not belong to the Clovis culture. Africa is the most likely origin of the PaleoAmericans, because the Ice sheet along the Pacific shoreline of North America, Siberia and Alaska, would have made the sea route from Asia or Europe unviable 65,000 years ago. The Dufuna boat dating back to 8,000 BC, shows that Africans had boats at this early date. The culture associated with the Dufuna boat dates back to 20,000 years ago.

Dugout canoes hewn from wood at Lake Malawi, East African Rift system. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Top Image: Rock paintings at Pedra Furada, Brazil ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

References

Bray, Warwick. 1988. “The Paleoindian debate”. Nature 332, (10 March), p.107.

Bryan, A. L. 1987. “Points of Order”. Natural History , pp.7-11.

Guidon, N. and Delibrias, G. 1986. “Carbon-14 dates point to man in the Americas 32,000 years ago.” Nature 321:769-771.

Guidon, N., and B. Arnaud. 1991. “The chronology of the New World: Two faces of one reality.” World Arch. 23(2):167-178.

Guidon, N., et al.1996. “Nature and Age of the Deposits in Pedra Furada, Brazil: Reply to Meltzer, Adovasio & Dillehay,” Antiquity, 70:408.

Haynes,Jr., C.V. 1988. “Geofacts and Fanny”. Natural History ,(February)pp.4-12.

Kumar, Mohi. 2014. DNA From 12,000-Year-Old Skeleton Helps Answer the Question: Who Were the First Americans? [Online] Retrieved 16 August 2016 at : http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/dna-12000-year-old-skeleton-helps-answer-question-who-were-first-americans-180951469/?no-ist

Martin, P. S. and R.G.Klein (eds.), Quarternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution , (Tucson:University of Arizona Press,1989) p.111.

Neves, W. A. and Pucciarelli, H. M. 1989. Extra-continental biological relationships of early South American human remains: a multivariate analysis. Cieˆncia e Cultura, 41: 566–75

Neves, W. A. and Pucciarelli, H. M. 1990. The origins of the first Americans: an analysis based onthe cranial morphology of early South American human remains. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 81: 247.

Neves, W. A. and Pucciarelli, H. M. 1991. Morphological affinities of the first Americans: an exploratory analysis based on early South American human remains. Journal of Human Evolution, 21: 261–73.

Neves, W. A. and Meyer, D. 1993. The contribution of the morphology of early South and Northamerican skeletal remains to the understanding of the peopling of the Americas. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 16 (Suppl): 150–1.

Neves, W. A., Powell, J. F., Prous, A. and Ozolins, E. G. 1998. Lapa Vermelha IV Hominid 1: morphologial affinities or the earliest known American. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 26(Suppl): 169.

Neves, W. A., Powell, J. F. and Ozolins, E. G. 1999a. Extra-continental morphological affinities of Palli Aike, southern Chile. Intercieˆncia, 24: 258–63.

Neves, W. A., Powell, J. F. and Ozolins, E. G. 1999b. Modern human origins as seen from the peripheries. Journal of Human Evolution, 37: 129–33.

Neves W.A . and Pucciarelli H.M. 1991. “Morphological Affinities of the First Americans: an exploratory analysis based on early South American human remains”. Journal of Human Evolution 21:261-273.

Neves W.A ., Powell J.F. and Ozolins E.G. 1999. “Extra-continental morphological affinities of Lapa Vermelha IV Hominid 1: A multivariate analysis with progressive numbers of variables. Homo 50:263-268

Neves W.A ., Powell J.F. and Ozolins E.G. 1999. “Extra-continental morphological affinities of Palli-Aike, Southern Chile”. Interciencia 24:258-263. [Online] Available at: http://www.interciencia.org/v24_04/neves.pdf

Neves, W.A., Gonza´ lez-Jose´ , R., Hubbe, M., Kipnis, R., Araujo, A.G.M., Blasi, O., 2004. Early Holocene Human Skeletal Remains form Cerca Grande, Lagoa Santa, Central Brazil, and the origins of the first Americans. World Archaeology 36, 479-501

Neves, W. A., and M. Hubbe. 2005. Cranial morphology of early Americans from Lagoa Santa, Brazil: Implications for the settlement of the New World. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:18,309–18,314.

Powell,J.F. (2005). First Americans:Races, Evolution and the Origin of Native Americans. Cambridge University Press.

Winters,C. (2015). THE PALEOAMERICANS CAME FROM AFRICA, jirr. Vol. 3 (3) July-September, pp.71-83/Winter. [Online] Available at: https://www.academia.edu/17137182/THE_PALEOAMERICANS_CAME_FROM_AFRICA

Clyde Winters

Dr. Clyde Winters is an Educator , Anthropologist and Linguist. He has taught Education and Linguistics at Saint Xavier University -Chicago. Dr. Winters is the author of numerous articles on anthropology, archeogenetics and linguistics. His articles have appeared in the Journal. Read More

Comments

I am not sure that the m1 (Mt) markers in Tanzania hold up, since the most recent I have read suggests a back migration. Almost ALL African MtDNA is haplotype L NOT M or N.

Now of course IF (and it is a bloody big IF) people stop thinking “out of africa” and start thinking “out of SEA or even Melanesia, you just MIGHT be able show show a link between paleo Indians, Melanesian Australoid and Africans. In these case the “eve Mit DNA is l3 or M or N (any one of these would work) rather than L0 which is the current accepted assumption.

In this case you would be looking at some very early split somewhere along the Pacific Rim that eventually sent the L descendants towards Africa and the Ms towards Australia and India and Melanesia may be also towards South America. This would explain any language and place name similarities and also the possibility that the Del Fuegans used click languages like the San.

The N lineage and its descendants (R and B) seem to be just a little younger than the Ms and if you look at the current distributions seemed to have reached the Americas from the traditional Northern route (ie via B).

To throw in something else that has been bugging me for years – well before modern haplotype analysis is the ABSENCE of A and B type bloods in the Americas and in Tasmania and of B in Australia. I do not really buy the founder effect ideas because they would need to happen TWICE which is unlikely and the whole “pathogen” explanation just does not gel with me – sure if there were low frequencies etc but absence altogether.

So a very early split from an original proto human population of ABO mixture into two populations – first an AO population (eg San and Andaman Islanders and Australians) and then (probably quite soon afterwards) a further split into an O only population that went on to Tasmania and then (I have no idea HOW) reached South America.

Adding in the mtDNA you would have had in the dim dark past the following populations, possibly all existing at the same time, separated by distance or possibly water:

G1. Somewhere in SEA a group of “originals” who would probably be dark skinned, Negrito and Melanesian in appearance with mixed ABO and also mixed MN blood groups and principal Mt DNA M (or L3). They may well have carried BOTH the blood groups C and c and probably the remnant Du group

G2 Moving TOWARDS the South – Australia and Indonesia and India you have the AO group who are also Mt group M. In appearance they would be similar to group 1. They lose the Du

G2.1 The closest living relations could be the some Australians ie those with mt DNA M and derivatives

G2.2 On the opposite edge of the distribution moving towards South India you would have a group like the Andamanese

G3. At the outer edge of one of these this AO groups (probably G2.1) you have a further split into an O mono type. This group reaches Tasmania and possibly South America. They would be Mt M with various descendant subtypes. It would be expected that they would have a negrito/australoid appearance

G4 Meanwhile some our proto group G1 move towards Africa somewhere collecting the Mt L haplotypes and also LOSING the C blood group. They also lose the N bloodgroup. The closest living descendants are possibly some of the Pygmy tribes.

G5 at about the same time our prop group splits into a Melanesian group who lose the c and M blood groups but retain ABO blood and N and C blood. They would be Mt M

G6 The foremothers of the San are a little confusing because they share the Mt L of group 4 and blood groups a little more typical of the Andamanese. With rather lighter skin than both Melanesians and Pygmies it seems possible they originated somewhere in colder climates.

Anyway this is a very different perspective that maybe helps think about the possible paleo Indians

Source https://www.npr.org/2007/10/08/15040888/coming-to-america-who-was-first

Source https://www.chimuadventures.com/blog/2018/12/south-america-first-timers-region-right/

Source https://www.ancient-origins.net/opinion-guest-authors/did-paleoamericans-reach-south-america-first-006592