Journeys of hope: what will migration routes into Europe look like in 2021?

Early European Imperial Colonization of the New World

By the early to mid-seventeenth century, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands were all competing for colonies and trade around the world. Beginning in the late fifteenth century, explorers, conquerors, missionaries, merchants, and adventurers sought to claim new lands to colonize. It was only a matter of time before imperial rivals butted heads over land possession and trade routes. Competition for land grabs, settlement, trade, and exploration led to the growth of New World imperialism and the economic system of mercantilism. As European nations squabbled and settled lands, much was to be lost on the side of the indigenous Americans. Native populations shifted and decreased from the time of settlement onward.

Guiding Question

Which label best describes the very first wave of European immigration to the Americas in the late fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries: explorers, missionaries, merchants, or conquerors?

Objectives

Basic-level objective: Skill set: map identification; recall; description; analysis

- Geographically, what areas of the New World were western Europeans interested in settling?

- What motivated western European powers (France, the Netherlands, England, Spain, and Portugal) to migrate and settle the New World?

Intermediate-level objective: Skill set: compare and contrast; analysis

- How did these European powers differ in their colonization plans?

- What conflicts arose over competition for land acquisitions in the New World?

Advanced-level objective: Skill set: evaluation and drawing inferences

- Which label best describes the very first wave of European immigrants to the Americas: explorers, missionaries, merchants, or conquerors?

Vocabulary: imperial; missionaries; imperialism; mercantilism; indigenous

Lesson Procedures

After the introduction and warm-up activity students will read and analyze five different types of materials: a map, three pieces of artwork, and three primary documents. They will then be asked to write a follow-up argumentative writing sample that answers the Guiding Question with support from the materials. Along the way they are to work in groups to actively support one another in the learning of the materials. Each group will have to answer questions that accompany the materials.

Preparation Instructions

Warm-up Activity: Designed to entice the students into learning about Spanish colonization.

Read Bartolome de Las Casas’s narrative: A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, Seville, Spain, 1552

A full text is available here.

These People were found by them to be Wise, Grave, and well dispos’d, though their usual Butcheries and Cruelties in opressing them like Brutes, with heavy Burthens, did rack their minds with great Terror and Anguish. At their Entry into a certain Village, they were welcomed with great Joy and Exultation, replenished them with Victuals, till they were all satisfied, yielding up to them above Six Hundred Men to carry their Bag and Baggage, and like Grooms to look after their Horses: The Spaniards departing thence, a Captain related to the Superiour Tyrant returned thither to rob this (no ways diffident or mistrustful) People, and pierced their King through with a Lance, of which Wound he dyed upon the Spot, and committed several other Cruelties into the bargain. In another Neighboring Town, whose Inhabitants they thought, were more vigilant and watchful, having had the News of their horrid Acts and Deeds, they barbarously murdered them all with their Lances and Swords, destroying all, Young and Old, Great and Small, Lords and Subject without exception.

disposed: killed, dead

brutes: beast like

burthens: old form of the word burden

anguish: hardships

exultation: joy, happiness

victuals: food

diffident: shy, timid

vigilant: guarding, watchful

Display the following image from the Brown University Archive of Early American Images, also available as a PDF here.

Questions for Discussion:

- According to sixteenth-century historian Bartolome de Las Casas, how did the Spanish treat the indigenous people they encountered in the New World?

- How does the drawing in the Las Casas book display the Spanish? How does it display the indigenous people?

Lesson Activities

Differentiated Instruction 1: Geography of New World Colonization

Please use a map of the Age of Exploration outlining exploration and routes of the Spanish, English, and French (included in most texts and available online) and an atlas or modern political map to compare and contrast.

Questions for Discussion

- What modern nations did Spanish explorers sail to?

- What modern nations did English explorers sail to?

- What modern nations did French explorers sail to?

- What would motivate these Europeans to venture into unknown lands and risk death?

- How have these explorers left their mark on the areas they explored?

Differentiated Instruction 2: Using Art to Assess Spanish Exploration and Colonization

Display William Henry Powell’s Discovery of the Mississippi, 1853

This painting is in the US Capitol Rotunda and can be further studied at the Architect of the Capitol’s website.

Provide students with a basic introduction to the painting, including:

- This painting was made in 1853, three hundred years after the event portrayed.

- The main figure of this painting is Hernándo de Soto, a Spanish explorer who led the first Europeans to visit the Mississippi River and parts of southeastern North America.

Group Work and Questions for Discussion:

- Identify three figures wearing different types of clothing in this painting. Attempt to give them a job title or character title.

- What items in this painting display power?

- What items in this painting display religion?

- How can this painting relate to what motivated the Spanish to explore and colonize the New World?

Differentiated Instruction 3: Captain John Smith

Note that this is written in an older form of English, which can be discerned by having the teacher read this aloud while students read along silently.

Background Information: Captain John Smith was a late sixteenth-/early seventeenth-century Englishman who was a sailor, explorer, and colonist. His adventures in the New World and the settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, paved the way for further English colonization. This letter was published in England to entice Englishmen to migrate to the New World.

LONDON

Printed for John Tappe, and are to bee solde at the Greyhound in Paules-Church yard, by W.W.

1608

Anchoring in this Bay, twentie or thirtie went a shore with the Captain, and in coming aboard, they were assalted with certaine Indians, which charged them within Pistoll shot: in which conflict, Captaine Archer and Mathew Morton were shot: whereupon, Captaine Newport seconding them, made a shot at them, which the Indians little respected, but having spent their arrowes retyred without harme, and in that place was the Box opened, wherin the Counsell for Virginia was nominated: and arriving at the place where wee are now seated, the Counsell was sworne, the President elected, which for that yeare was Maister Edm. Maria Wingfield, where was made choice for our scituation a verie fit place for the erecting of a great cittie, about which some contention passed betwixt Capatain Wingfield and Captaine Gosnold, notwithstanding all our provision was brought a shore, and with as much speede as might bee wee went about our fortification.

I tolde him being in fight with Spaniards our enemie, being overpowred, neare put to retreat, and by extreame weather put to this shore: where landing at Chesipiack, the people shot us, but Kequoughtan they kindly used us: we by signes demaunded fresh water, they described us up the River was all fresh water: at Paspahegh also they kindly used us: our Pinnsse being leake, we were inforced to stay to mend her, till Captaine Newport my father came to conduct us away.

Questions for Discussion

- What problems did John Smith and his crew face in exploring and settling in the New World?

- How does John Smith portray the Spanish?

- How does John Smith portray the indigenous people he encountered?

Differentiated Instruction 4: Samuel de Champlain

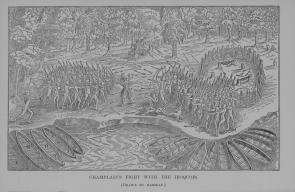

Image study: Deffaite des Yroquois au Lac de Champlain, 1613, published by Chez Iean Berjon, also available from the Library of Congress. This engraving depicts French explorer Samuel de Champlain’s encounter with the Iroquois at the site of modern-day Lake Champlain.

Questions for Discussion

- How does this engraving depict the indigenous people?

- Who has the military advantage according to this image? Why?

Pair this engraving with the following primary source written by Samuel de Champlain in his Memoirs of Samuel de Champlain Books I and II:

Of all the most useful and excellent arts, that of navigation has always seemed to me to occupy the first place. For the more hazardous it is, and the more numerous the perils and losses by which it is attended, so much the more is it esteemed and exalted above all others, being wholly unsuited to the timid and irresolute. By this art we obtain knowledge of different countries, regions, and realms. By it we attract and bring to our own land all kinds of riches, by it the idolatry of paganism is overthrown and Christianity proclaimed throughout all the regions of the earth. This is the art which from my early age has won my love, and induced me to expose myself almost all my life to the impetuous waves of the ocean, and led me to explore the coasts of a part of America, especially of New France, where I have always desired to see the Lily flourish, and also the only religion, catholic, apostolic, and Roman. This I trust now to accomplish with the help of God, assisted by the favor of your Majesty, whom I most humbly entreat to continue to sustain us, in order that all may succeed to the honor of God, the welfare of France, and the splendor of your reign, for the grandeur and prosperity of which I will pray God to attend you always with a thousand blessings, and will remain,

MADAME, Your most humble, most obedient, and most faithful servant and subject, CHAMPLAIN.

exalted: highly honored

irresolute: undecided

idolatry: worship of idols

Lily: reference to the French symbol of royalty, the fleur de lis

Questions for Discussion

- Summarize the passage: “For the more hazardous it is, and the more numerous the perils and losses by which it is attended, so much the more is it esteemed and exalted above all others, being wholly unsuited to the timid and irresolute.”

- What religious plans does Champlain wish to accomplish in the New World?

- What does the reference “I have always desired to see the Lily flourish” mean?

Differentiated Instruction 5: Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh

Note that this is written in an older form of English, which can be discerned by having the teacher read this aloud while students read along silently. This reading is a charter given to Sir Walter Raleigh. Raleigh was an English sailor and adventurer who explored and claimed land in North America for the English Crown.

Questions for Discussion

- What does this charter give Sir Walter Raleigh permission to do?

- How does this charter describe the inhabitants of the New World?

- If you were to label Raleigh’s mission to the New World, which label would it be and explain why?

ELIZABETH by the Grace of God of England, Fraunce and Ireland Queene, defender of the faith, &c. To all people to whome these presents shall come, greeting.

Knowe yee that of our especial grace, certaine science, and meere motion, we haue given and graunted, and by these presents for us, our heires and successors, we giue and graunt to our trustie and welbeloued seruant Walter Ralegh, Esquire, and to his heires assignee for euer, free libertie and licence from time to time, and at all times for ever hereafter, to discover, search, finde out, and view such remote, heathen and barbarous lands, countries, and territories, not actually possessed of any Christian Prince, nor inhabited by Christian People, as to him, his heires and assignee, and to every or any of them shall seeme good, and the same to haue, horde, occupie and enjoy to him, his heires and assignee for euer, with all prerogatives, commodities, jurisdictions, royalties, privileges, franchises, and preheminences, thereto or thereabouts both by sea and land, whatsoever we by our letters patents may graunt, and as we or any of our noble progenitors haue heretofore graunted to any person or persons, bodies politique.or corporate: and the said Walter Ralegh, his heires and assignee, and all such as from time to time, by licence of us, our heires and successors, shall goe or trauaile thither to inhabite or remaine, there to build and fortifie, at the discretion of the said Walter Ralegh, his heires and assignee, the statutes or acte of Parliament made against fugitives, or against such as shall depart, romaine or continue out of our Realme of England without licence, or any other statute, acte, lawe, or any ordinance whatsoever to the contrary in anywise notwithstanding.

preheminences: permanencies: those that surpass all others

jurisdictions: areas where law applies

Journeys of hope: what will migration routes into Europe look like in 2021?

I n 2020, tens of thousands of migrants crossed desert and sea, climbed mountains and walked through forests to reach what has become an increasingly inhospitable Europe. Many of them died, overwhelmed by the waves, or tortured in the detention centres of Libya. More were displaced after the flames of Moria refugee camp in Greece burned everything they had.

As a new year begins, so do the journeys of tens of thousands more people seeking a new life overseas. The Guardian has spoken to experts, charity workers and NGOs about the challenges and risks they face on the main migration routes into Europe.

The Balkan route

Migrants walk in protest to the Serbian-Hungarian border near Kelebija, Serbia, in February 2020. They seek a passage to the EU. Photograph: Bernadett Szabo/Reuters

In July last year, seven north African men climbed into a shipping container in a railway yard in Serbia, hoping to emerge a few days later in Milan. Three months later, on 23 October, authorities in Paraguay found their badly decomposed bodies inside a shipment of fertiliser. Violence from security forces in the Balkan states has pushed people to take even greater risks to reach Europe.

After the Serbian border with EU countries became virtually impassable in 2018, refugees began trying to reach Croatia via Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) instead. The path usually begins in Turkey, from which migrants attempt to reach Bulgaria or Greece, then North Macedonia or Serbia, then Bosnia, Croatia and Slovenia, from where they can finally reach Italy or Austria.

The final leg of the Balkan route, which crosses mountains and snow-covered forests and lacks facilities for migrants, is one of the most perilous and gruelling, made worse by the brutal pushbacks carried out by squadrons of Croatian police who patrol the EU’s longest external border. Between January and November 2020, the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) recorded 15,672 pushbacks from Croatia to BiH. More than 60% of cases reportedly involved violence.

The humanitarian situation for those entering Bosnia and Herzegovina remains unacceptable and undignified

“The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 has decreased migration flows along the western Balkan route,” says Nicola Bay, DRC country director for Bosnia. Last year, 15,053 people arrived in BiH, compared with 29,196 in 2019. “But in the absence of real solutions the humanitarian situation for those entering BiH remains unacceptable and undignified.”

In December, a fire destroyed a migrant camp in Bosnia, which had been built to contain the spread of Covid-19 among the migrant population. The same day the International Organization for Migration declared the effective closure of the facility. The destruction of the camp, which was strongly criticised by rights groups as inadequate due to its lack of basic resources, has left thousands of asylum seekers stranded in snow-covered forests and subzero temperatures.

When countries in the region begin to ease Covid-19 restrictions this year, Bay says it is highly likely there will be a surge of arrivals to BiH, which remains the main transit point for those wanting to reach Europe – a scenario for which the EU and the region remain unprepared.

Greece

Carrying children and their few possessions, migrants flee in Moria camp on the island of Lesbos, Greece. Photograph: Angelos Tzortzinis/AFP/Getty Images

On the night of 8 September, the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos, the biggest of its kind in Europe, burst into flames. The government announced a four-month state of emergency on the island, as thousands of vulnerable asylum seekers were displaced.

“This was one of the most terrible years for asylum seekers arriving in Greece,” says Stephan Oberreit, head of mission for Médecins Sans Frontières in Greece. “The combination of violence, Covid pandemic and the continued harmful policies of containment on the islands have led to several breaking points and eventually to the fires that have destroyed Moria.”

After the blaze, the EU said there would be no more Morias. But more than 15,000 men, women and children are still trapped in miserable conditions on the Greek islands and the policy of containment continues.

People using this route generally come by dinghy from the Turkish town of Ayvalik, aiming to reach Lesbos.

Oberreit says that while arrivals have decreased this year, reports of illegal pushbacks have increased “in a concerning way”. “But let’s be realistic, people will continue to try to cross and risk their lives in the absence of other safer and legal options.”

Oberreit says the pandemic “has been used by Greek authorities to accelerate their agenda to create closed centres on the Greek islands and to increase the border controls”.

It’s hard to predict what will happen this year, “but the signs we have today give us little hope that the situation for the people who manage to arrive on the Greek islands will improve. Or that the EU will abandon its approach based on deterrence and containment,” he says.

Central Mediterranean

Migrants are rescued by members of the Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms after leaving Libya on an overcrowded dinghy in November. Photograph: Sergi Camara/AP

In mid-November, four shipwrecks in the space of three days claimed the lives of more than 110 people in the Mediterranean, including at least 70 people whose bodies washed up on the beach of al-Khums, in western Libya. Taking advantage of good autumn weather, people smugglers sent hundreds of migrants to sea. Many of the journeys ended in tragedy.

Last year, at least 575 people died taking the central Mediterranean route. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says the real number is considerably higher.

People using this route usually depart from Tripoli or Zuwara in Libya, or from Sfax in Tunisia, and make for the Sicilian island of Lampedusa or Malta in small boats.

At the start of the pandemic, Italy and Malta declared their ports closed. Rome established “quarantine boats” – ferries on which migrants are placed under quarantine for 14 days, which have been criticised by human rights groups.

“There is not the adequate medical care on the ferries that these people badly need and not even legal assistance,” says Oscar Camps, founder of Proactiva Open Arms. “In such a situation, human rights are practically revoked.”

Open Arms is now the only NGO rescue boat operating along the central Mediterranean route. Many other rescue boats are blocked in Italian ports because officials refuse to authorise their departure.

Camps says he would like to see a planned civil or military rescue operation along the route this year, similar to Operation Mare Nostrum, which Italy ran in 2013–2014. “It should be an operation aimed at dismantling Libyan armed groups, falsely called coastguards, financed by the EU, whose only mission is to intercept boats and bring them back to a country at war,” says Camps. “However, considering the way things are going, we would settle for them stopping the criminalisation of rescue operations carried out by humanitarian ships.”

The Channel

A migrant climbs into the back of a lorry bound for Britain at the entrance to the Channel tunnel in Calais, November 2020. Photograph: Denis Charlet/AFP/Getty Images

Several thousand people attempted to cross the Channel to reach Britain last year. London has repeatedly pressed Paris to do more to prevent people leaving France. In November, the home secretary, Priti Patel, and her French counterpart, Gérald Darmanin, said they wanted to make the route unviable and signed a new agreement aimed at curbing the number of migrants crossing the Channel in small boats. More than 8,000 people made the crossing in small boats last year, up from almost 1,900 in 2019.

“The difficulties faced by women, men and children will in many ways remain the same as before,” says Steve Valdez-Symonds, Amnesty’s refugee and migrant rights programme director. “Clearly, there is no will among the two governments – particularly not the UK – to directly address the needs and circumstances of these people to ensure they have access to asylum.”

Whether the UK will secure some agreement with the EU or with France on family reunification is uncertain

According to experts, the future of the Channel migration route is linked to the continuing pandemic lockdowns and whether the UK participates in EU migration policies, specifically the EU family reunification programme.

“Whether the UK will secure some agreement with the EU or with France in relation to this particular matter is uncertain,” says Valdez-Symonds. “All that can be said, as things stand, is that almost the sole formally sanctioned option for at least unaccompanied children with family in the UK to seek asylum here is about to close.”

Sign up for the Global Dispatch newsletter – a fortnightly roundup of our top stories, recommended reads, and thoughts from our team on key development and human rights issues:

Indian Ocean Trade Routes

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/IndianOceanTrade-56a042475f9b58eba4af9165.jpg)

Dr. Kallie Szczepanski is a history teacher specializing in Asian history and culture. She has taught at the high school and university levels in the U.S. and South Korea.

The Indian Ocean trade routes connected Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and East Africa, beginning at least as early as the third century BCE. This vast international web of routes linked all of those areas as well as East Asia (particularly China).

Long before Europeans “discovered” the Indian Ocean, traders from Arabia, Gujarat, and other coastal areas used triangle-sailed dhows to harness the seasonal monsoon winds. Domestication of the camel helped bring coastal trade goods such as silk, porcelain, spices, incense, and ivory to inland empires, as well. Enslaved people were also traded.

Classic Period Indian Ocean Trading

During the classical era (4th century BCE–3rd century CE), major empires involved in the Indian Ocean trade included the Achaemenid Empire in Persia (550–330 BCE), the Mauryan Empire in India (324–185 BCE), the Han Dynasty in China (202 BCE–220 CE), and the Roman Empire (33 BCE–476 CE) in the Mediterranean. Silk from China graced Roman aristocrats, Roman coins mingled in Indian treasuries, and Persian jewels sparkled in Mauryan settings.

Another major export item along the classical Indian Ocean trade routes was religious thought. Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism spread from India to Southeast Asia, brought by merchants rather than by missionaries. Islam would later spread the same way from the 700s CE on.

Indian Ocean Trade in the Medieval Era

![]()

John Warbarton-Lee / Getty Images

During the medieval era (400–1450 CE), trade flourished in the Indian Ocean basin. The rise of the Umayyad (661–750 CE) and Abbasid (750–1258) caliphates on the Arabian Peninsula provided a powerful western node for the trade routes. In addition, Islam valued merchants—the Prophet Muhammad himself was a trader and caravan leader—and wealthy Muslim cities created an enormous demand for luxury goods.

Meanwhile, the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties in China also emphasized trade and industry, developing strong trade ties along the land-based Silk Roads, and encouraging maritime trade. The Song rulers even created a powerful imperial navy to control piracy on the eastern end of the route.

Between the Arabs and the Chinese, several major empires blossomed based largely on maritime trade. The Chola Empire (3rd century BCE–1279 CE) in southern India dazzled travelers with its wealth and luxury; Chinese visitors record parades of elephants covered with gold cloth and jewels marching through the city streets. In what is now Indonesia, the Srivijaya Empire (7th–13th centuries CE) boomed based almost entirely on taxing trading vessels that moved through the narrow Malacca Straits. Even the Angkor civilization (800–1327), based far inland in the Khmer heartland of Cambodia, used the Mekong River as a highway that tied it into the Indian Ocean trade network.

For centuries, China had mostly allowed foreign traders to come to it. After all, everyone wanted Chinese goods, and foreigners were more than willing to take the time and trouble of visiting coastal China to procure fine silks, porcelain, and other items. In 1405, however, the Yongle Emperor of China’s new Ming Dynasty sent out the first of seven expeditions to visit all of the empire’s major trading partners around the Indian Ocean. The Ming treasure ships under Admiral Zheng He traveled all the way to East Africa, bring back emissaries and trade goods from across the region.

Europe Intrudes on the Indian Ocean Trade

![]()

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

In 1498, strange new mariners made their first appearance in the Indian Ocean. Portuguese sailors under Vasco da Gama (~1460–1524) rounded the southern point of Africa and ventured into new seas. The Portuguese were eager to join in the Indian Ocean trade since European demand for Asian luxury goods was extremely high. However, Europe had nothing to trade. The peoples around the Indian Ocean basin had no need for wool or fur clothing, iron cooking pots, or the other meager products of Europe.

As a result, the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean trade as pirates rather than traders. Using a combination of bravado and cannons, they seized port cities like Calicut on India’s west coast and Macau, in southern China. The Portuguese began to rob and extort local producers and foreign merchant ships alike. Still scarred by the Moorish Umayyad conquest of Portugal and Spain (711–788), they viewed Muslims in particular as the enemy and took every opportunity to plunder their ships.

In 1602, an even more ruthless European power appeared in the Indian Ocean: the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Rather than insinuating themselves into the existing trade pattern, as the Portuguese had done, the Dutch sought a total monopoly on lucrative spices like nutmeg and mace. In 1680, the British joined in with their British East India Company, which challenged the VOC for control of the trade routes. As the European powers established political control over important parts of Asia, turning Indonesia, India, Malaya, and much of Southeast Asia into colonies, reciprocal trade dissolved. Goods moved increasingly to Europe, while the former Asian trading empires grew poorer and collapsed. With that, the two-thousand-year-old Indian Ocean trade network was crippled, if not completely destroyed.

Source https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/early-european-imperial-colonization-new-world

Source https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jan/14/journeys-of-hope-what-will-migration-routes-into-europe-look-like-in-2021

Source https://www.thoughtco.com/indian-ocean-trade-routes-195514