What It Was Really Like For Native Americans Who Traveled To Europe

Native American History Timeline

As explorers sought to colonize their land, Native Americans responded in various stages, from cooperation to indignation to revolt.

As explorers sought to colonize their land, Native Americans responded in various stages, from cooperation to indignation to revolt.

Long before Christopher Columbus stepped foot on what would come to be known as the Americas, the expansive territory was inhabited by Native Americans. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, as more explorers sought to colonize their land, Native Americans responded in various stages, from cooperation to indignation to revolt.

After siding with the French in numerous battles during the French and Indian War and eventually being forcibly removed from their homes under Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, Native American populations were diminished in size and territory by the end of the 19th century.

Below are events that shaped Native Americans’ tumultuous history following the arrival of foreign settlers.

1492: Christopher Columbus lands on a Caribbean Island after three months of traveling. Believing at first that he had reached the East Indies, he describes the natives he meets as “Indians.” On his first day, he orders six natives to be seized as servants.

April 1513: Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Leon lands on continental North America in Florida and makes contact with Native Americans.

February 1521: Ponce de Leon departs on another voyage to Florida from San Juan to start a colony. Months after landing, Ponce de Leon is attacked by local Native Americans and fatally wounded.

May 1539: Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto lands in Florida to conquer the region. He explores the South under the guidance of Native Americans who had been captured along the way.

October 1540: De Soto and the Spaniards plan to rendezvous with ships in Alabama when they’re attacked by Native Americans. Hundreds of Native Americans are killed in the ensuing battle.

C. 1595: Pocahontas is born, daughter of Chief Powhatan.

1607: Pocahontas’ brother kidnaps Captain John Smith from the Jamestown colony. Smith later writes that after being threatened by Chief Powhatan, he was saved by Pocahontas. This scenario is debated by historians.

1613: Pocahontas is captured by Captain Samuel Argall in the first Anglo-Powhatan War. While captive, she learns to speak English, converts to Christianity and is given the name “Rebecca.”

1622: The Powhatan Confederacy nearly wipes out Jamestown colony.

1680: A revolt of Pueblo Native Americans in New Mexico threatens Spanish rule over New Mexico.

1754: The French and Indian War begins, pitting the two groups against English settlements in the North.

May 15, 1756: The Seven Years’ War between the British and the French begins, with Native American alliances aiding the French.

May 7, 1763 : Ottawa Chief Pontiac leads Native American forces into battle against the British in Detroit. The British retaliate by attacking Pontiac’s warriors in Detroit on July 31, in what is known as the Battle of Bloody Run. Pontiac and company successfully fend them off, but there are several casualties on both sides.

1785: The Treaty of Hopewell is signed in Georgia, protecting Cherokee Native Americans in the United States and sectioning off their land.

Native American Leaders

1788/89: Sacagawea is born.

1791: The Treaty of Holston is signed, in which the Cherokee give up all their land outside of the borders previously established.

August 20, 1794: The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the last major battle over Northwest territory between Native Americans and the United States following the Revolutionary War, commences and results in U.S. victory.

November 2, 1804: Native American Sacagawea, while 6 months pregnant, meets explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their exploration of the territory of the Louisiana Purchase. The explorers realize her value as a translator

April 7, 1805: Sacagawea, along with her baby and husband Toussaint Charbonneau, join Lewis and Clark on their voyage.

November 1811: U.S. forces attack Native American War Chief Tecumseh and his younger brother Lalawethika. Their community at the juncture of the Tippecanoe and Wabash rivers is destroyed.

June 18, 1812: President James Madison signs a declaration of war against Britain, beginning the war between U.S. forces and the British, French and Native Americans over independence and territory expansion.

March 27, 1814: Andrew Jackson, along with U.S. forces and Native American allies attack Creek Indians who opposed American expansion and encroachment of their territory in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. The Creeks cede more than 20 million acres of land after their loss.

May 28, 1830: President Andrew Jackson signs the Indian Removal Act, which gives plots of land west of the Mississippi River to Native American tribes in exchange for land that is taken from them.

1836: The last of the Creek Native Americans leave their land for Oklahoma as part of the Indian removal process. Of the 15,000 Creeks who make the voyage to Oklahoma, more than 3,500 don’t survive.

1838: With only 2,000 Cherokees having left their land in Georgia to cross the Mississippi River, President Martin Van Buren enlists General Winfield Scott and 7,000 troops to speed up the process by holding them at gunpoint and marching them 1,200 miles. More than 5,000 Cherokee die as a result of the journey. The series of relocations of Native American tribes and their hardships and deaths during the journey would become known as the Trail of Tears.

1851: Congress passes the Indian Appropriations Act, creating the Indian reservation system. Native Americans aren’t allowed to leave their reservations without permission.

October 1860: A group of Apache Native Americans attack and kidnap a white American, resulting in the U.S. military falsely accusing the Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache tribe, Cochise. Cochise and the Apache increase raids on white Americans for a decade afterwards.

November 29, 1864: 650 Colorado volunteer forces attack Cheyenne and Arapaho encampments along Sand Creek, killing and mutilating more than 150 American Indians during what would become known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

Recommended for you

Who Was Squanto and What Was His Role in the First Thanksgiving?

Louisiana

Paris Commune of 1871

April 29, 1868: The U.S. Government and the Sioux Nation sign the Treaty of Fort Laramie. In this treaty, the United States recognizes the Black Hills of Dakota as the Great Sioux Reservation, the exclusive territory of the Sioux (Dakota, Lakota and Nakota) and Arapaho people. But after gold is discovered in the Black Hills, miners and settlers begin moving onto the land en masse. Native resistance to the treaty’s violation culminates in the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. In 1980, the Supreme Court rules that the Black Hills were illegally confiscated, and awards the Sioux more than $100 million in reparations. Sioux leaders reject the payment, saying the land had never been for sale.

November 27, 1868: General George Armstrong Custer leads an early morning attack on Cheyenne living with Chief Black Kettle, destroying the village and killing more than 100 people, including many women and children and Black Kettle himself.

1873: Crazy Horse encounters General Custer for the first time.

1874: Gold discovered in South Dakota’s Black Hills drives U.S. troops to ignore a treaty and invade the territory.

June 25, 1876: In the Battle of Little Bighorn, also known as “Custer’s Last Stand,” Lieutenant Colonel George Custer’s troops fight Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, along Little Bighorn River. Custer and his troops are defeated and killed, increasing tensions between Native Americans and white Americans.

October 6, 1879: The first students attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the country’s first off-reservation boarding school. The school, created by Civil War veteran Richard Henry Pratt, is designed to assimilate Native American students.

February 8, 1887: President Grover Cleveland signs the Dawes Act, giving the president the authority to divide up land allotted to Native Americans in reservations to individuals.

December 15, 1890: Sitting Bull is killed during a confrontation with Indian police in Grand River, South Dakota.

December 29, 1890: U.S. Armed Forces surround Ghost Dancers led by Chief Big Foot near Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota, demanding the surrender of their weapons. An estimated 150 Native Americans are killed in the Wounded Knee Massacre, along with 25 men with the U.S. cavalry.

January 29, 1907: Charles Curtis becomes the first Native American U.S. Senator.

September 1918: Choctaw soldiers use their native language to transmit secret messages for U.S. troops during World War I’s Meuse-Argonne Offensive on the Western Front. The Choctaw Telephone Squad provide Allied forces a critical edge over the Germans.

June 2, 1924: U.S. Congress passes the Indian Citizenship Act, granting citizenship to all Native Americans born in the territorial limits of the country. Previously, citizenship had been limited, depending on what percentage Native American ancestry a person had, whether they were veterans, or, if they were women, whether they were married to a U.S. citizen.

March 4, 1929: Charles Curtis serves as the first Native American U.S. Vice President under President Herbert Hoover.

May 1942: Members of the Navajo Nation develop a code to transmit messages and radio messages for the U.S. armed forces during World War II. Eventually hundreds of code talkers from multiple Native American tribes serve in the U.S. Marines during the war.

April 11, 1968: The Indian Civil Rights Act is signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, granting Native American tribes many of the benefits included in the Bill of Rights.

July 1968: Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt found the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis, along with Bellecourt’s brother Vernon and Banks’ friend George Mitchell. Originally an urban-focused movement formed in response to police brutality and racial profiling, AIM grows rapidly in the 1970s to become the driving force behind the Indigenous civil rights movement.

November 20, 1969: A group of San Francisco Bay-area Native Americans, calling themselves “Indians of All Tribes,” journey to Alcatraz Island, declaring their intention to use the island for an Indian school, cultural center and museum. Referencing Europeans’ colonization of North America, they claim Alcatraz is theirs “by right of discovery.” On June 11, 1971 armed federal marshals descend on the island and remove the last of its Indian residents.

August 29, 1970: A group of Native Americans, led by the San Francisco-based United Native Americans, ascend 3,000 feet to the top of Mount Rushmore and set up camp to protest the broken Treaty of Fort Laramie.

November 26, 1970: On Thanksgiving Day, AIM members seize a replica of the Mayflower in Boston Harbor, declaring the holiday a National Day of Mourning.

June 6, 1971: A group of Native Americans, led by AIM, occupy Mount Rushmore to demand the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie be honored. Twenty Native Americans—nine men and 11 women—are eventually arrested.

October 1972: Hundreds of Native Americans drive in caravans, beginning at the West Coast, to the offices of the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C. in a movement called the Trail of Broken Treaties. During the occupation, AIM releases the Twenty Points, a list of demands that includes the re-recognition of Native tribes, abolition of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and federal protections for Indigenous cultures and religions. The occupiers hold the BIA office for a week.

February 27, 1973: The Wounded Knee Occupation begins as some 200 Oglala Lakota (also referred to as Oglala Sioux) and AIM members seize and occupy the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The occupation lasts for 71 days, during which time two Sioux men are shot to death by federal agents and several more are wounded.

January 4, 1975: Congress passes the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which reverses the termination policy of previous decades when American Indian tribes were disbanded, their land sold and “relocations” forced Indians off reservations and into urban centers. The 1975 act provides recognition and funds to Indian tribes.

July 15, 1978: A transcontinental trek for Native American justice, called the “Longest Walk,” sets off from Alcatraz Island, California. By the time marchers reach Washington, D.C. they number 30,000.

August 11, 1978: The American Indian Religious Freedom Act is passed, granting Native Americans the right to use certain lands and controlled substances for religious ceremonies.

October 11, 1980: President Jimmy Carter signs the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act. The act grants Indian tribes, including the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Penobscot, $81.5 million for land taken from them more than 150 years ago.

November 16, 1990: President George H.W. Bush signs the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA into law. The act requires federal agencies and museums that receive federal funds to repatriate Native American cultural items to their respective peoples.

October, 1991: The National Coalition of Racism in Sports and Media (NCRSM) is established by leaders at the National Congress of American Indians to organize against the use of Indian names, logos, symbols and mascots in sports.

July 13, 2020: The Washington National Football League franchise announces it is dropping its name, the “Redskins,” as well as its Indian head logo. The move is in response to decades of criticism that they are offensive to Native Americans. The team is eventually renamed the Commanders.

March 15, 2021: Representative Deb Haaland of New Mexico is confirmed as secretary of the Interior, making her the first Native American to lead a cabinet agency. “Growing up in my mother’s Pueblo household made me fierce,” Haaland Tweeted after her confirmation. “I’ll be fierce for all of us, our planet, and all of our protected land.”

July 23, 2021: In response to criticisms, Cleveland’s Major League Baseball team announces they are changing their name to the Guardians and are dropping their previous name, the Indians.

What It Was Really Like For Native Americans Who Traveled To Europe

Much has been made of the various European-led conquests, expeditions, and contacts that deeply changed the fabric of Native American life beginning centuries ago. Whether that’s Christopher Columbus arriving in what’s now Puerto Rico in 1493, Vikings settling down in Canada, or any other similar tale, however, that’s not the whole story. As it turns out, the Atlantic Ocean has never been a one-way only journey. Plenty of people have been moving both west and east across its waters, including quite a few Native Americans who undertook wide-ranging voyages.

The stories of how Native Americans traveled from their homelands to Europe are as unique as the individuals that made these journeys. Some traveled in search of a better life, while others were stolen from their people and only made their way back home after years of travel. Some were greeted as royalty. Quite a few were treated as exoticized spectacles, while others may have felt similarly about the European ways of life they encountered.

Furthermore, the Native Americans who were able to tell the tales of their travels had plenty to say about their experiences in the lands across the sea, presenting a complex view of societies that would interact with native ones for generations to come. Here’s what it was really like for Native Americans who traveled to Europe.

A Native American woman likely visited Iceland 1,000 years ago

Many people likely believe that Native American people first visited Europe sometime after Europeans made contact, perhaps when Christopher Columbus first arrived in North America in the late 15th century, or Hernan Cortes brought down the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521. However, that’s not actually the case. For one, according to UNESCO, the L’Anse aux meadows site in Newfoundland, Canada, has produced clear evidence that Norse people had briefly settled on North America’s Atlantic Coast some time in the 11th century. What’s more, that Viking connection could very well mean that one of the first native people to visit Europe actually did so more than a millennia ago.

This surprising revelation didn’t come about because of archaeological excavations as much as it did through the work of modern-day geneticists. The Guardian reports that scientists undertaking a gene-mapping survey of people in Iceland found that some modern people there carried genes that were clearly from a Native American woman. Next to nothing is known about her life, but it’s likely that she was taken by or traveled of her own accord with Vikings from her North American home to the southern coast of Iceland sometime in the year 1000.

Pocahontas saw 17th century London

Much has been made of the life of Powhatan woman Pocahontas. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, “Pocahontas” was actually a nickname, while she more often would have gone by Amonute or, in more private contexts, Matoaka. Per History, she did meet English explorer and vagabond John Smith, but that’s where the similarities with Disney end. Pocahontas was eventually abducted by English colonists and made to live their lifestyle, complete with baptism, a new name, and marriage to tobacco farmer John Rolfe.

By 1616, Pocahontas was “Rebecca Rolfe.” The Virginia Company, which had funded the English colony, pushed for her to travel back to Europe in part to show that they had achieved the goal of converting Native Americans. Pocahontas would have also been a convenient figurehead for fundraising. In 1616, she, her husband, their infant son, and a small group of Powhatan people sailed for England.

Once in London, the National Archives reports, Pocahontas was treated as both royalty and curiosity. She attended a ball held by King James I, met the queen, and even met John Smith again. In 1617, Pocahontas and her party were set to return to Virginia, but she took ill soon after they set sail. She died in Gravesend, Kent, probably aged only 21. Her husband and young son sailed for home, leaving her buried at St. George’s Church, as per Atlas Obscura.

Black Elk performed for Queen Victoria

Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux from what would eventually become the state of Wyoming, saw much of the world. As per the National Park Service, he not only saw massive changes over the course of his life from the 1860s to 1950, but he traveled widely as part of the popular Wild West Show. Black Elk joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s show in 1886, hoping to better understand the world of white people to help the Sioux through a tumultuous and oftentimes cruel transition away from native life.

Black Elk and other Native American people traveled to England in 1887 as part of the show. As ThoughtCo reports, that’s also where Queen Victoria happened to be preparing for her Golden Jubilee celebrations in honor of her 50th year as monarch. She wanted to see Buffalo Bill’s show and, being the queen, Victoria got what she wanted.

That’s where Black Elk first saw the queen, says American History (via HistoryNet), whom he called “Grandmother England.” Only Victoria and her entourage were in attendance for the full performance. Black Elk and other Indigenous performers danced for her. As Black Elk recalled, “she was little but fat and we liked her.” After shaking hands with her post-performance, he reported that “Her hand was very little and soft.” Victoria, for her part, later wrote in her diaries that the Native Americans looked “alarming.”

Squanto returned from his journey to find devastation

Though generations of American schoolchildren knew him as “Squanto,” the man who would eventually act as a liaison between the Pilgrims and Native Americans was actually named Tisquantum. And, in contrast to the simplified and oftentimes overly cheerful retellings of his part in early American colonial history, the true story of Tisquantum is one full of tragedy.

As Smithsonian Magazine reports, in 1614, a group of Patuxet people went out to meet a ship that had appeared nearby. On board they met captain John Smith — yes, that John Smith — in a peaceful encounter. Later, however, Smith’s associate, Thomas Hunt, lured another group of Patuxet aboard and took them captive. Those that survived the fight were sailed back to Europe and sold into slavery, including Tisquantum.

The Revealer says that he was first sold in Spain to a group of Catholic priests who hoped to convert him. He eventually left them, went to England, and finally returned to Massachusetts six years after he left. Yet, when he arrived, Tisquantum found his people wiped out by disease and the Puritan settlement of Plymouth in their place. And while Tisquantum did help the people there, he also played hostile Indigenous people against one another, perhaps seeking some small amount of stability for himself. He later died of illness in Plymouth, having made himself a complicated figure in both native and colonial communities.

A group of Osage people traveled to France in 1827

In 1827, a group of six Osage people — four women and two men — undertook the long journey from their home in Missouri to France. Once in Europe, they were treated to plenty of acclaim and VIP experiences but were also gawked at and treated as “noble savages.” They also may have been kidnapped.

According to Osage News, it all began in Missouri with a group of 12 Osage people. Things went south relatively quickly when some of their boats overturned during a river crossing, causing six of the party to turn back. The other six finally made it to France after a three-month voyage east across the Atlantic, landing in July 1827. They were escorted by David Delauney, who intended to make money by exhibiting the group.

Once there, the group encountered some unique experiences, according to An Osage Journey to Europe. These included a ride in a hot air balloon and a meeting with the French king. Yet, as the group traveled throughout Europe, interest declined, and their finances began to dwindle. As the State Historical Society of Missouri says, Delauney was eventually thrown into debtors’ prison, leaving the Osage to their own devices. One woman, Sacred Sun, gave birth to twin girls and allowed a Belgian couple to adopt one baby. They eventually made it back home to Missouri after the Marquis de Lafayette helped pay for their return passage.

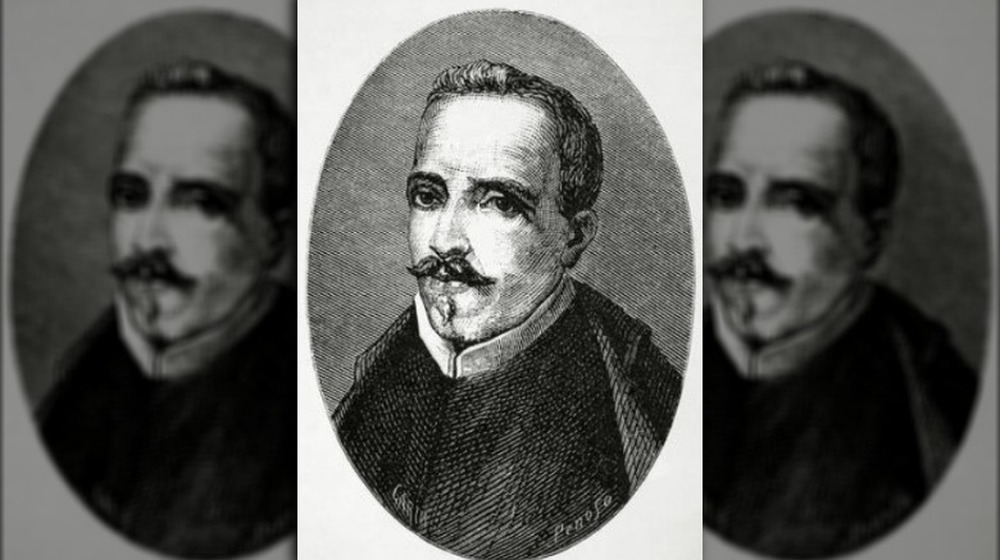

Garcilaso de la Vega crossed the Atlantic and became a famous writer

Born in 16th century Peru after the Spanish conquest of the region, Garcilaso de la Vega would cross both a continent and an ocean to land in Europe and build a new life there. According to the University of Notre Dame, he was the son of a conquistador and Isabel Suarez Chimpu Ocllo, an Incan noble and niece of a local ruler. Garcilaso was raised in the household of his father, Sebastian Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas. The young boy, who was part of a group of people of mixed heritage that would be known as mestizos, came into contact with both traditional Incan culture and colonial Spanish practices.

Garcilaso was an intelligent child who was useful as a scribe for his father, as Britannica reports. In late 1560, the young man, also known as “El Inca,” traveled to Spain and enlisted in the Spanish army. He became a captain, then left and took on the mantle of a Catholic priest in 1597. Later, he began translating literary works and wrote his own famous historical accounts of Peru, which were published beginning in 1608.

A trip to London was fatal for Kamehameha II and his wife

As author Shannon Selin explains, the trouble all began when Kamehameha II wrote to King George IV, pushing for British protection of the Hawaiian Islands and asking for his fellow monarch’s advice. Already in the first decades of the 19th century, Hawaii and its monarchy were facing numerous outside threats, from disease, to economic issues, to Americans ready to move in to exploit the island’s positions and resources. George IV basically gave Kamehameha II the cold shoulder and never replied to the letter. Kamehameha then commissioned a ship to take him, his favorite wife Kamamalu, and an entourage of Hawaiian representatives, straight to the British court. They landed in England in May 1824.

According to The Hawaiian Journal of History, many British newspapers simply recounted the retinue’s comings and goings, though a few were more overtly racist and disparaging of the king’s retinue, with one publication reminding its readers that the king “is still a savage” despite his Western dress and fine manners.

Though Kamehameha and Kamamalu traveled through London society and met with plenty of people, the meeting with George IV was frustratingly slow in coming. It was eventually scheduled but then delayed after the Hawaiian entourage caught measles. With practically no immunity to the disease, Kamamalu and Kamehameha died in quick succession in July 1824. The remaining Hawaiian dignitaries finally met with the British king in September before sailing home with the remains of their royals.

Wanchese left the Roanoke people for England

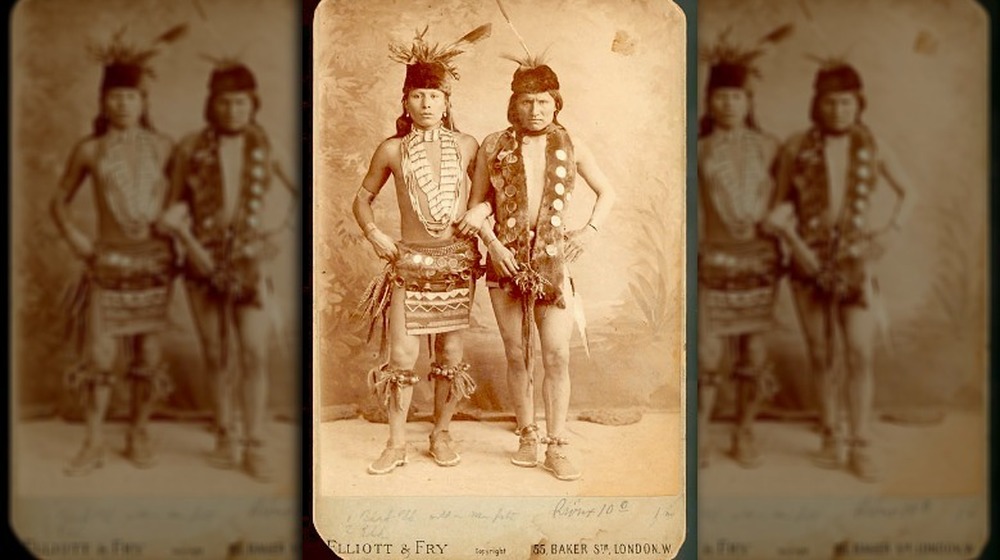

In 1584, Wanchese, a leader of the Roanoke tribe in modern day North Carolina, traveled to England as one of the first recorded Native Americans to make the crossing. According to the Coastwatch, he traveled with a fellow Native American, Manteo, as part of an effort by local leaders to establish friendly relations with English traders. The pair sailed with the Arthur Barlowe back to England, where they stayed for a time at the mansion of Sir Walter Raleigh. During their stay, they traded their clothing for Western-style garments, learned English, and taught some Algonquian to scientist Thomas Hariot. While they were being studied, however, both Wanchese and Manteo undertook their own mission to gather as much intel about these foreigners as they could.

Though both men returned home safely, something went sour for Wanchese along the way. As Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America reports, upon his return, Wanchese turned his back on any European contacts. Perhaps, having seen his fair share of British society up close, he had concluded that his Roanoke people were better off facing their native enemies on their own, without British backup. Certainly, as per the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, he was no friend to the Europeans who settled on Roanoke Island in 1586, being part of the group of Indigenous people who drove the newcomers away.

Manteo traveled across the Atlantic for political reasons

As a pretty high-up member of Croatoan society, it wasn’t terribly shocking that Manteo would be chosen to represent his people in Europe. As the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography states, Manteo traveled to England by 1584 with another native person, the Roanoke man Wanchese.

Once there, the two men changed to British-style clothing and even visited the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Transatlantic Encounters says that they were there both to gather information for their tribes back home but also to make economic connections, both for themselves and for the associated Sir Walter Raleigh.

Where Wanchese grew distrustful of the English and eventually turned back from his associations with foreigners, Manteo maintained relations with the colonists. He may have even been baptized into the Anglican church upon his return to North America, which, as Transatlantic Encounters notes, would have made him the first known Native American to convert to Anglicanism. However, it appears that his conversion may have been only political, as it would have placed him in a potentially more advantageous position regarding the English who were slowly but surely invading his people’s lands.

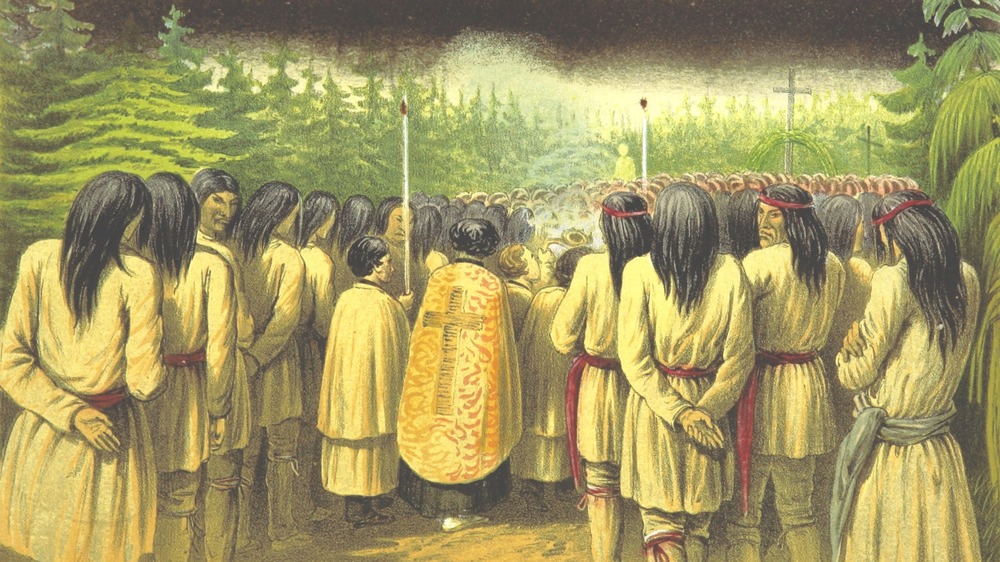

Mesoamerican Totonac people visited Europe in 1519

Some of the earliest recorded native visitors to Europe hailed from Mesoamerica. The American Historical Review reports that the Totonac people, who had allied themselves with Hernan Cortes against the Aztec inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, sent a small group to Spain in 1519.

However, scanty documentation means that not much is known about who exactly made the crossing and why. The group likely included both men and women and probably was sent in part to shore up royal support for Cortes, who had gone ahead with the conquest of Mexico without the go-ahead from the Spanish king.

When questioned by the Spanish court, the Totonacs carefully replied that they were definitely happy to have been baptized as Christians, and that all of the treasure they were handing over was a gift and not plunder Cortes had ripped from their lands. The truth of how the Totonac representatives really felt will likely never be known.

For their part, European observers were equal parts fascinated and horrified by the Mesoamerican visitors. German Renaissance artist Albercht Durer even came across the group and their gold, writing that he had seen “a sun all of gold a whole fathom broad, and a moon all of silver of the same size . very strange clothing, beds, and all kinds of wonderful objects of human use.” The awe-struck Durer concluded that he “marvelled at the subtle Ingenia of men in foreign lands.”

One English explorer kidnapped multiple Inuit people

English explorer Martin Frobisher thought that he was going to make it big. Per Transatlantic Encounters, his 1576 expedition started off with Queen Elizabeth I waving at them from a window, a pretty good sign overall. But his attempt to find a northern passage through the Arctic to Asia, thus bypassing the troublesome North American landmass, was an utter mess. Out of his three-ship expedition, one sunk, one turned back, and only his flagship made it to Baffin Island in what’s now Canada. Yet, for the Inuit people living on Baffin Island, their luck would prove to be far worse than Frobisher’s.

Perhaps wanting to make up for an expensive and embarrassing failure, Frobisher abducted an unnamed Inuit man and sailed back to London by October 1576. The native man died only two weeks later, either from a self-inflicted wound or a respiratory disease.

Frobisher repeated this whole affair in 1577, when he returned to Baffin Island and stole three more Inuit people — a man, a woman, and her young child. Per Transatlantic Encounters, the man, Kalicho, died on November 7 of what appears to have been an infection and wounds received during his capture. The woman, Arnaq, died four days later of what was probably measles. A short time later, her son Nutaaq also died. Frobisher would later return to Baffin Island but took no more captives, presumably to the relief of the increasingly wary Inuit.

Pastedechouan’s trip to Europe proved tragic upon his return

Some Native Americans adjusted as well as they could to their experiences in Europe. They either dressed as they normally did back home or adopted clothing more common to their new environment. Some learned European languages, while a few taught their own to foreigners. But some Native Americans had traumatic experiences that shaped the rest of their lives. That is perhaps nowhere more true than in the sad story of Pastedechouan.

According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Pastedechouan was an Innu man born sometime before 1620, probably in Quebec. The Recollet religious order took a young Pastedechouan to France, had him baptized, and re-named him Pierre-Antoine. Pastedechouan was relatively well-educated by his religious foster family, learning both French and Latin. He returned to Quebec in 1626 but had trouble reconnecting with his Montegnais people, possibly because he had forgotten his native language.

Things did not exactly get better for Pastedechouan from there. In 1629, English forces came to invade Canada and recruited Pastedechouan as an interpreter, though he fled as soon as he could. He eventually left the Catholic faith but, apparently having trouble supporting himself and evidently dealing with alcoholism, often teamed up with missionaries out of financial necessity. As The Betrayal of Faith reports, it is in these moments that Pastedechouan becomes most pitiable — undone by drink, he rails against seemingly everyone in a world that, towards the end, seemed to hold little joy for him.

British & European History 1700-1850

This strand of our one-year MSt or two-year MPhil in History is the equivalent of a free-standing Master’s in the history of Britain and Europe in the long eighteenth century, the age of enlightenment and revolutions.

Recent generations of historians have risen to the challenge of finding ways of characterising this period that transcend older notions of a passage from ‘traditional’ to ‘modern’. How best to characterise Enlightenment, and what it meant to whom, continues to attract controversy, as do the causes, nature and effects of revolutions, political and other. There has been lively interest in developments in state forms and in the ‘public sphere’, in attempts to promote new systems of ‘manners’ (whether industrious, polite or democratic) and increasingly in interactions between Europe and the wider world.

Oxford has a strong tradition of work including interdisciplinary work on British history in the long eighteenth century, on the enlightenment and on the French revolution and its effects. The outstanding print resources of the Bodleian Library are complemented by a wealth of digital resources, accessible to students on-course wherever in the world they may be working. Alongside faculty research seminars focussing on this period (see e.g. ‘Oxford Seminar in Mainly British History 1680-1850’ community page on Facebook), there are seminars and workshops at the Voltaire Foundation (www.voltaire.ox.ac.uk), which is dedicated to ‘disseminating research in the enlightenment’. TORCH hosts an interdisciplinary network for ‘Romanticism and eighteenth-century studies’, RECSO (www.recso.org).

Course Organisation

Alongside the Theory and Methods course, students spend their first term studying Sources and Historiography. In weekly 90-minute classes, students will be asked to reflect upon and discuss critically current approaches to major themes in the history of the period, including for example the Enlightenment and the Public Sphere, Revolution and Terror, Globalisation, and Romanticism and Nationalism – in relation to debates over intellectual and cultural history, the history of emotions, material culture and transnational history. Students will also be asked to make presentations and discuss the application to their own research topics of the research methods presented in plenary sessions.

Meanwhile, in the ‘Skills’ component of the course, students will be encouraged to take advantage of opportunities to improve their reading knowledge of European languages, to attend library information sessions and training sessions organised by Oxford University Computing Services – so as to learn e.g. about text analysis software, GIS or statistical packages.

In the second term, students take one of a wide portfolio of Option courses. Those particularly relevant to Britain and Europe 1700-1850 typically include:

State and society in early modern Europe

In recent decades the political history of early modern Europe has re-invented itself in dialogue with social, economic and cultural history. Analyses of state formation and political culture have aspired to replace biographies of statesmen, narratives of party struggle and genealogies of institutional development. This course examines a series of themes in the development of early modern states to test models of political change on a range of societies from the British Isles to Eastern Europe. It aims to equip those interested in reformations, counter-reformations, rebellions, courts, parliaments, towns, nobles, peasants and witches – and in statesmen, factions and institutions – with the ideas and comparators needed to frame a sophisticated research project in their chosen field. Class topics will include:

- the military-fiscal state

- clientage and faction

- confessionalisation

- justice and the law

- government, economy and social change

- household order

- communication, propaganda and magnificence

- communication, representation and revolt

The dawn of the global world, 1450-1800: ideas, objects, connections

The ‘globalization’ of history has been the most visible and significant development in historical scholarship of the past decade or so. Historians are increasingly aware of the need to place their work in a context that spills over national, regional, or civilizational boundaries. Some of the most exciting work has emerged from probing the global dimensions of the ‘early modern period’ before the rise of European world domination. This course will introduce the two principal methodologies involved in doing this new large-scale history – the connective and the comparative – through a series of seminars led by one European historian and a different specialist in cultures outside of Europe each week. In pursuit of the connective we will consider what happened when Europeans began to traverse the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and became entangled in a newly diverse range of societies. For example, what kind of architecture resulted when Portuguese ecclesiastical styles were transplanted to the tropics? Other weeks will take a more comparative approach. Considering the way in which Chinese intellectuals turned to classical texts in formulating ‘Neo-Confucianism’, for example, should help us see the over-familiar European themes of Renaissance and Reformation in a new light.

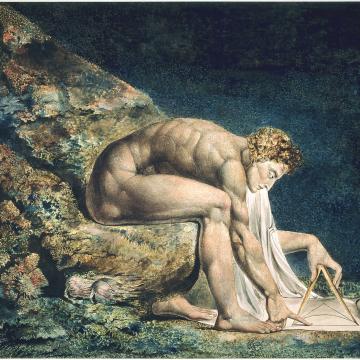

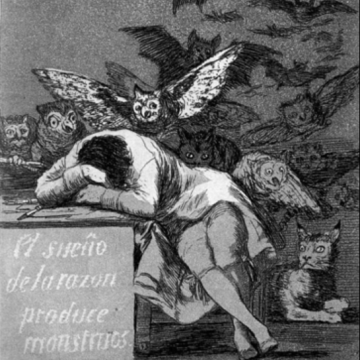

The Enlightenment, c. 1680-1800: Ideas and the public sphere

This option offers the opportunity to engage with a range of exciting new scholarship on the Enlightenment, covering the period from the second half of the seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth century. It takes inspiration from recent rebuttals of the postmodern critique of the ‘Enlightenment project’, and addresses the subject in comparative and transnational perspective. We shall cover Enlightenment both as an intellectual movement and as a social phenomenon, examining how thinkers across Europe engaged with new publics. For the first four weeks we shall explore the major interpretative issues now facing Enlightenment historians, including:

- the coherence of Enlightenment – whether we should think in terms of one Enlightenment or several;

- the importance and duration of ‘radical’, irreligious Enlightenment;

- the relation between Enlightenment, the republic of letters, and the ‘public sphere’;

- the politics of Enlightenment: public opinion, reform, and revolution.

During the second half of the course, participants will be encouraged to set their own more precise study agenda, related to the topics of their course papers. They may explore in more detail the intellectual content of Enlightenment, its various contexts, its social framework, and its impact, within and across national and political frontiers. Topics which might be studied at this stage are:

- Enlightenment contributions to natural philosophy, and the ‘arts and sciences’;

- the Enlightenment ‘science of man’, as pursued in philosophy and political economy;

- writing sacred, civil and natural history in the Enlightenment;

- women, gender and Enlightenment.

Participants will also be encouraged to attend the research-oriented Enlightenment Workshop, which meets weekly in Hilary Term.

Selfhood in History: 1500 to the present

How have people understood the self in the past? How have they conceptualized emotions? Is there a self before 1700? How do different cultures conceive of the self and how do they understand spirituality? What is the relation between the individual self and the collective? This course seeks to understand ways of approaching the self and psychology in different times and places. It also seeks to explore ways of incorporating subjectivity and emotions of people in the past in how we write history; and to question the sociological, collective categories of analysis that historians often employ. Each session will take a particular example of a cultural context and explore how historians could write the history of subjectivity. The sessions will draw on different types of source material – diaries, letters, visual sources, material objects, travel writing, memoirs, court records, micro-historical material, oral history – and consider the problems and possibilities they offer. Four of the sessions will be on the early modern period; four will be on the modern period; however, in their assessed essay, students may concentrate on either the early modern or the modern period. The course deliberately bridges the early modern and the modern because the historiography itself does. This enables productive comparisons.

War in the Modern World

This course is an introduction to the history of warfare since ca.1780, taking the emergence of revolutionary warfare and the military divergence between Europe and the rest of the world as its starting-point. The course is organised both thematically and chronologically. Students will be asked to assess whether the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries saw the emergence of a new epoch in warfare, one marked within Europe by the emergence of mass conscript armies, and beyond it by a recent but rapid European military divergence from the rest of the world. They will explore the topics of war and empire – wars of colonial conquest in Asia, America and Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries – and be encouraged to explore whether this was enabled or facilitated by the developments of the military revolution. They will explore the distinctive forms and functions of warfare which emerged in the 19th century, notably the relationships between war and the various nation-building projects at the time, and the racialized violence of colonial warfare. ‘War and Technology’ will look at how certain types of technological advance – notably rifled weaponry, steam-powered, iron-hulled armoured warships, and later air power and land armour – transformed the way wars were fought, and the international relations surrounding them, while also exploring the role of medical science in warfare. The topic of Life, Death and the experience of war will ask if historians can recreate the subjective experience of the battlefield, and the medical and psychological consequences of warfare. ‘Total War’ will explore the total mobilisation of societies to meet the demands of 20th-century warfare, focusing on the First and Second World Wars.

Source https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-timeline

Source https://www.grunge.com/341123/what-it-was-really-like-for-native-americans-who-traveled-to-europe/

Source https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/british-european-history-1700-1850