A Brief History Lesson on Travel: Why, How, and Where We Traveled in the 1920s

A Brief History Lesson on Travel: Why, How, and Where We Traveled in the 1920s

Share:

This city park in Berlin is one of the most fascinating examples of gentrification. “A crown jewel of open space,” Tempelhoft, a favorite of citizens and tourists alike, was at one time one of the main pre-WW2 airports. The home of Lufthansa, it was constructed back in 1923 and continued operating until 2008. After its closing, Berliners fought hard to keep it as a public space and now, this unique structure houses communal gardens and hosts festivals.

This is the place we would show time travelers to illustrate how the world and our values have changed in 100 years. And how flying became so routine that we often choose to stay grounded.

Tempelhof’s 386-hectares have enough space for joggers, cyclists, picnic goers, and dog walkers

Source: visitBerlin.de

Initially, an area called Tempelhof Feld (field in German) quickly grew from a small aerodrome with a hangar to the world’s first airport with an underground railway and a terminal with a contemporary look. Although in the 1920s, air passenger travel was more of an indulgence than a necessity, the construction of an airfield was important for the future growth of the route network.

One hundred years ago, stuck between two wars and on the verge of the Great Depression, the world was optimistic, open to experiments, and hungry for freedom. And the Roaring Twenties delivered. Usually in our special Christmas commentary, we’ve explored the technology of today and the future. Now, with a new decade approaching, we look into the past. What was it like to experience traveling in the twenties of the 1900s? To board clunky planes, go on the first road trip, or even travel abroad and relax on a cruise ship? Let’s find out.

Vacation is the new normal

To the generation surviving World War I, life in the twenties was entirely new. Aggressive economic growth meant that luxury items were now mass-produced, and a typical middle-class family could afford the most revolutionary product – a car. Henry Ford implemented the 40-hour workweek, which improved the quality of life for a regular factory worker who now had weekends off and could join the consumerist middle class.

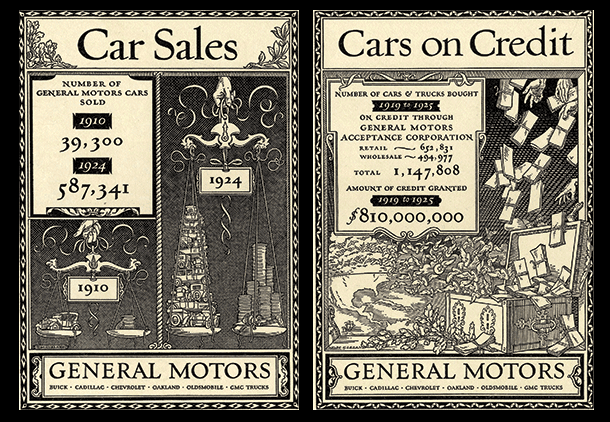

While most couldn’t afford a car for a one-time payment, they opted for credit.

General Motors practically invented car credit by offering prestige cars for manageable prices

By the end of the twenties, credit was used to purchase 90 percent of goods. Since splurging was more available and the work schedule became standardized, people were more inclined to take their families on vacation.

The most popular outbound destinations for Americans were the Caribbean, particularly Nassau, Jamaica, or Mexico. At one point, spending time on the beach was so widespread that the suntan went into fashion – a striking contrast to the centuries-old preference for fair skin.

While a car was becoming a common household posession, the most popular modes of transportation for the longest time remained trains and ocean liners.

Railroad – the symbol of the decade

Puffing locomotives, the distinctive sound of train horns, and engineers in overalls tending a firebox are some of the most distinctive images from the golden age of railroading. In the 1920s, trains had already existed for 100 years – about the same time we’ve lived with commercial aviation.

Because of World War II, railroads were nationalized, and the newly created US Railroad Administration invested in new equipment and established numerous changes and standards. A new design for a steam locomotive, an improved signal system, and stronger and quieter cars, made partially from steel (instead of wood), were some of the biggest implementations of the era.

Both in big cities and small towns, railway stations were focal points of community life. They were often the largest and most opulently decorated buildings in the area. Platforms filled with mingling crowds of people from all walks of life had an equalizing effect, while the trains themselves were less egalitaran. Ordinary people traveled on trains seated on simple wooden benches (or two-tier unfolding seats in sleeping cars). In the South until the end of Jim Crow laws, transportation was segregated, while white and black people traveled together in other parts of the country. Well-heeled travelers could afford cushioned cabins, usually designed by professional carpenters.

First-class train cabin with the view on the New Zealand planes

The pinnacle of long-distance travel were the sleeping, dining, and private cars first introduced by George M. Pullman in 1865. He was often invited by carriers to create luxurious cars – elaborately and excessively decorated, with plush seats and expensive chandeliers tinkling in response to the movement. The wealthy enjoyed Pullman cars well into the 20th century. Today, you can find a few Airbnb listings and book your stay in a restored car, now enabled with air conditioning and Wi-Fi.

An interesting detail present in most trains of that era were observation cars – last carriages of the train with a convenient platform for passengers to sightsee.

Passengers ready to enjoy the breeze, circa 1927

Prolonging the vacation on a cruise

After the RMS Titanic tragedy of 1912, the maritime standards of safety have been majorly revised and regular lifeboat inspections were introduced. These and many other changes have persuaded the public that sea travel was once again safe. By 1920s, ships and ocean liners became the trendiest mode of transportation. Because of that, the Suez Canal had to be widened to accommodate the increased traffic.

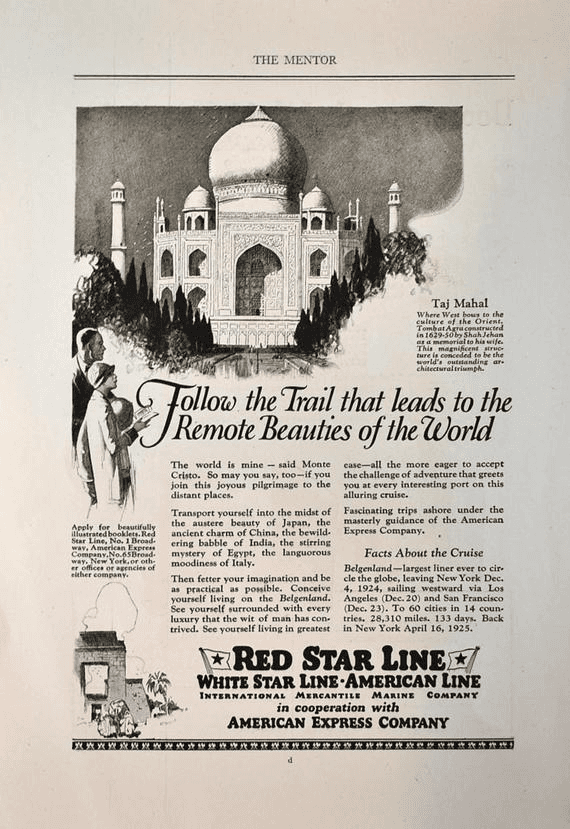

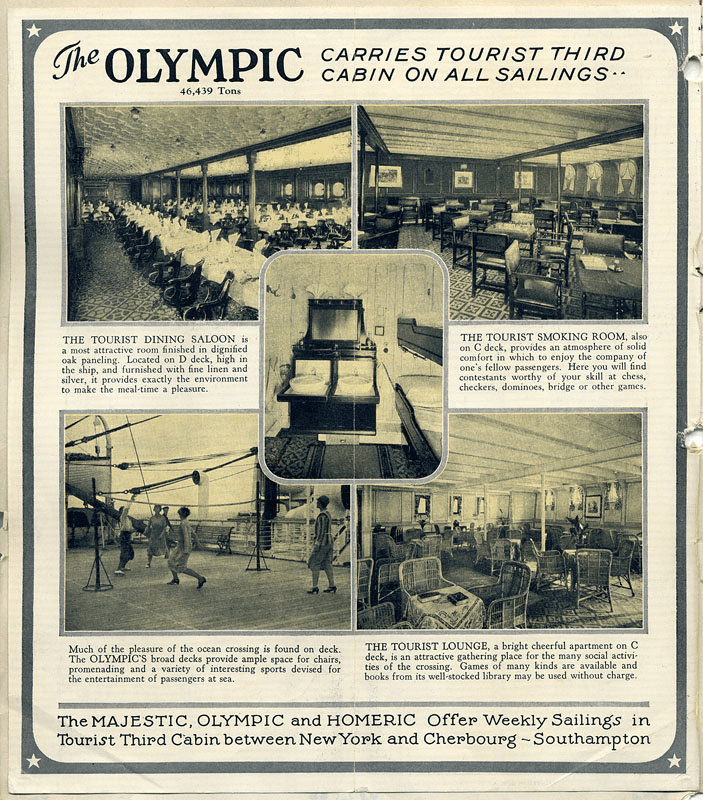

Transatlantic journeys were advertised as a part of the vacation, offering the wealthiest all types of entertainment from swimming pools to movie theaters. To make room for more people (and sell more tickets), ship decks were divided into different classes, so traveling to and from America got more affordable. Some carriers even introduced the fourth class, promising first-class comfort for a second-class price.

Advertisement depicting newly built spaces for the tourist class including a separate dining room and entertainment options

The prohibition law in the US enabled alcohol-seeking Americans to choose other international carriers, which inherently crippled the US passenger trade. Although the liner companies tried hard to entertain people, spending several days on a ship was still considered boring.

“Auto tourists” and camping

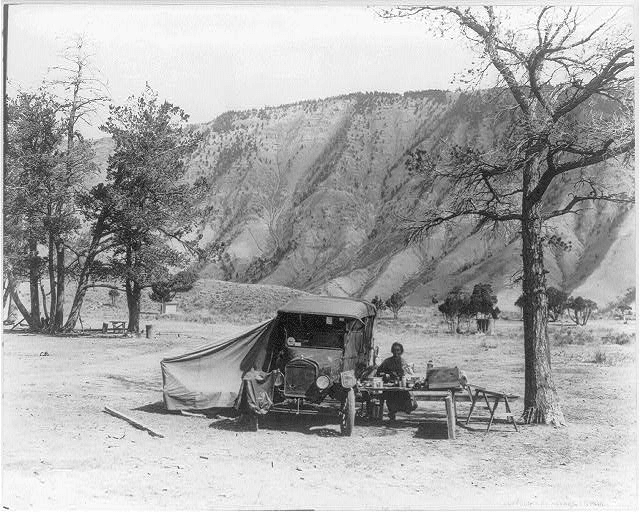

The twenties marked the beginning of the automobile era with the record-breaking Ford Model T selling massively across the country. This was the car that changed the living and traveling of most Americans as it was comparatively cheap and easy to drive. The Tin Lizzie not only provided a bit of privacy (most cars before were open-roofed) but also became a symbol of freedom – now young people could go anywhere anytime, of course, if muddy, country roads allowed.

People were traveling to special events like auto races or carnivals, or simply to the beach. Popular attractions included Luna Parks (amusement parks were a trend of the twenties) in Denver and Coney Island, national parks like Yellowstone and Grand Canyon, the Hollywood Sign (erected in 1923) and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

As more people took to the road in search of adventure, gas stations, cheap motor hotels (motels), convenience stores, and drive-in restaurants started popping up on the roadsides, shaping the modern American landscape.

The first travel trailers wouldn’t appear until the 30s, but road trippers often stayed at primitive campgrounds, where they put up their own tents. People whose property reached the largest highways would build tourist homes – usually one-story buildings with the most basic services to accommodate people for not more than one night.

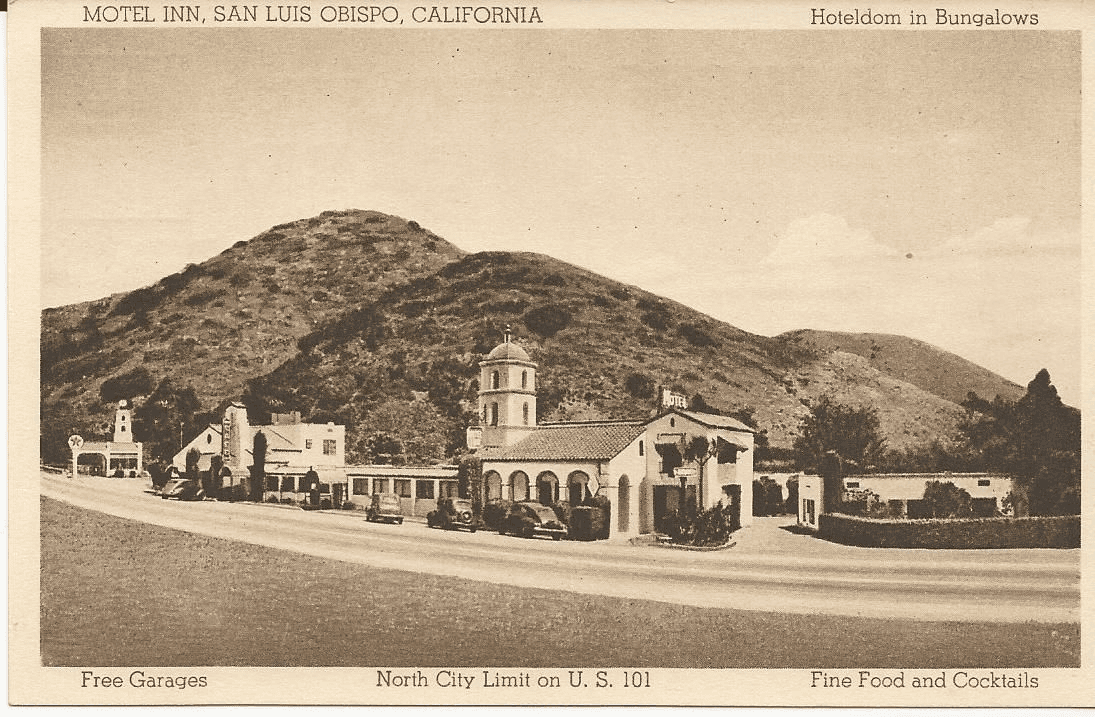

The world’s first motel opened in 1925 between San Francisco and Los Angeles. It was called Milestone Mo-Tel, charged $1.25 per night, and offered a private bathroom or even a garage in some cases. This was obviously an unseen level of comfort on the road. Before the chain grew across the country, the idea (and the naming) got picked up by lots of entrepreneurs, slowly turning the unique hospitality business into the current bonanza of cookie-cutter rooms.

This photo taken between the 1920s and 1930s reveals that Milestone Mo-Tel was almost a luxury location compared to its predecessors

The rare luxury of flying

Although the twenties are considered the beginning of commercial aviation, it was very much on an infancy. The first flight by KLM, the oldest operating airline, took place in 1920. It carried two British journalists from London to Amsterdam. Scheduled flights started running in 1921.

Here pictured Lady Hearth – the first female passenger on a commercial airline

A typical 1920s flying experience was luxurious in a very strange sense. It was expensive – the journey from West Coast to East Coast was about $360 (about $5000 if adjusted for inflation). The legroom was non-existent, the ride was bumpy, and it was cold since most airplane windows were simply holes in the fuselage. It took longer too and in most cases, you couldn’t travel at night. Somewhere in the middle of the flight, you would consider opting for a boat or a train next time.

As for the entertainment, passengers enjoyed food and drinks or watched a movie in an impromptu cinema (on a much rarer occasion). One of the first films shown in the air was The Lost World in 1925 by Imperial Airlines. The video below shows the preparations for the historical screening.

The golden age of travel ads

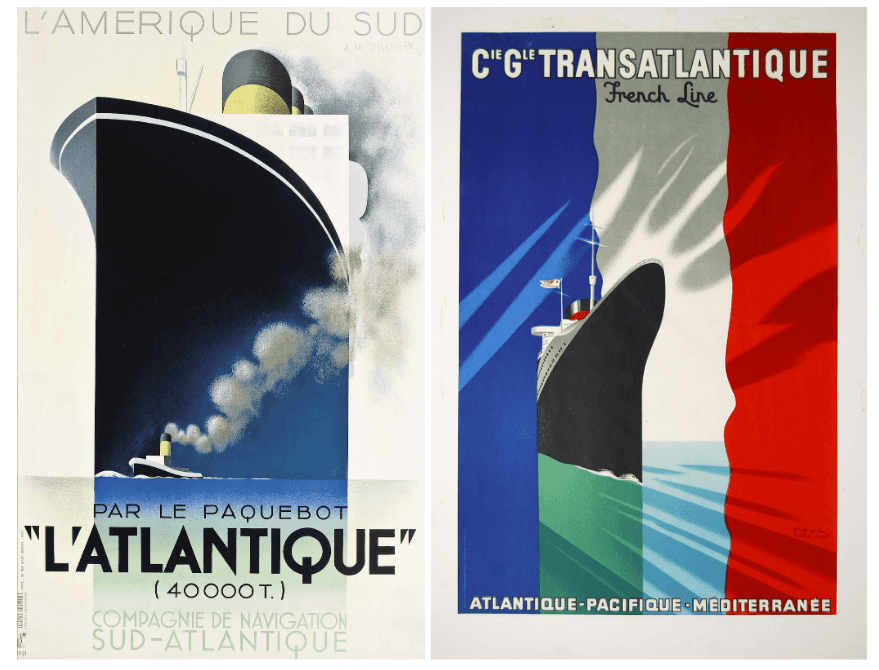

A few years ago, a 1931 poster advertising a French steamship line was sold for nearly £30,000. Such figures are not rare in the world of graphic art collectibles, though you can grab a similar original print on eBay for as low as a few thousand. The famous poster called L’Atlantique was created by one of the most influential graphic artists of the era and the father of the Machine Age style – Cassandre. Bold colors, horizontal lines, and the airbrushed effect replaced the Art Nouveau of the 1890s – the style that started to look out of place in the industrialist, wartime era. Art Deco, famously associated with the twenties, on the whole, dominated art appearing in train stations, window shops of travel agencies, and simply on the streets.

The Machine Age style used prominent angular typefaces, rounded contours, and confident lines

Railway and cruise companies commissioned famous designers like Cassandre, Paul Colin, Tom Purvis, and many others to create images that conveyed the sense of power and safety – basically, what travelers were supposed to feel boarding liners and trains. Travel agencies preferred more lavish details and colorful visuals, especially for exotic destinations like India, Hawaii, or Egypt.

Just like today, traditional ceremonies or spending time in nature were heavily advertised

Experimental and impactful, travel ads were some of the finest artwork of the decade. Although the promised experience was rarely delivered.

The growing industry of travel agencies

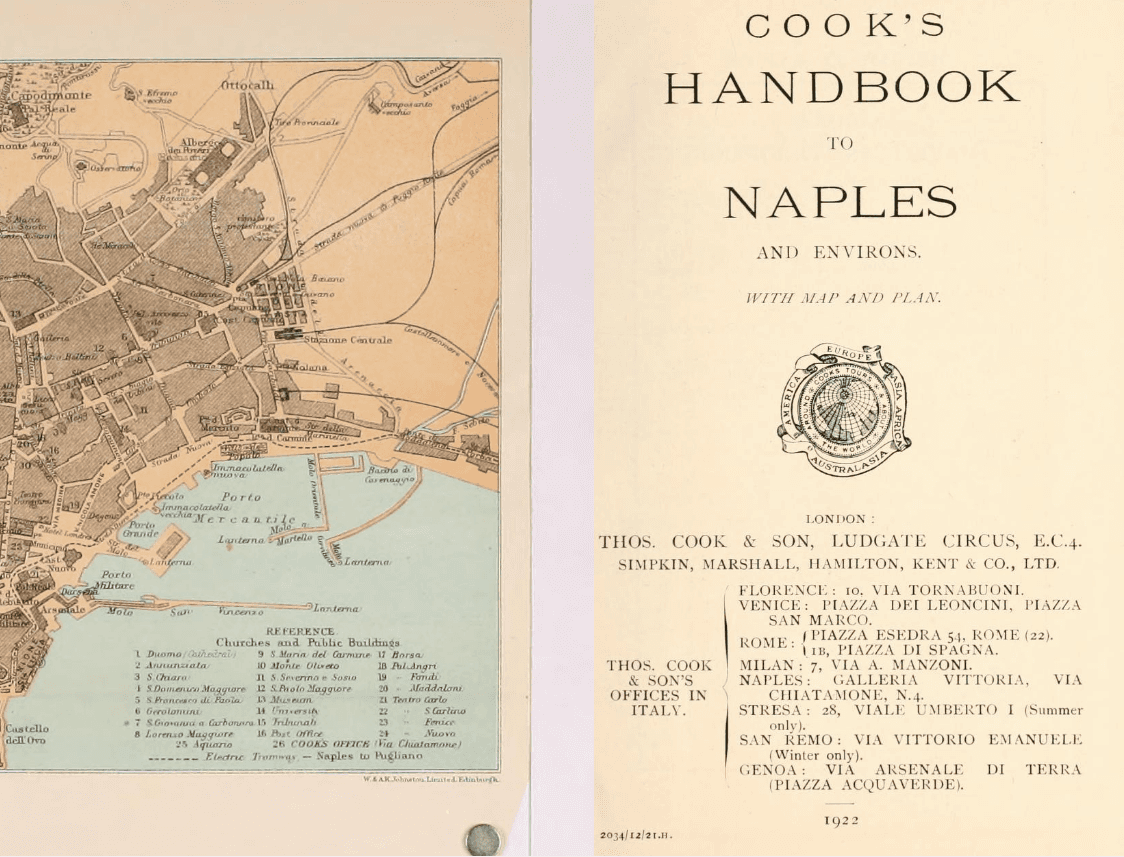

People of the 1920s were already avid customers of travel agencies. The oldest one established by Thomas Cook dates back to 1840. It was the first to organize an air tour from New York to Chicago in 1927, advertising the experience of flight rather than a mere mode of transportation.

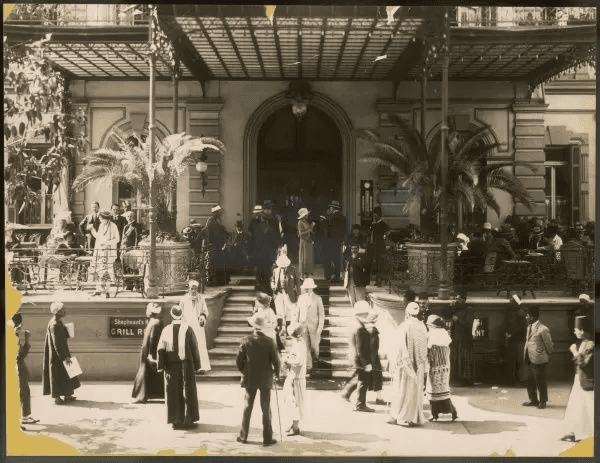

The tourist group outside a hotel in Cairo

For many, travel agencies were the only guarantee of their safety during the journey. If upper-class travelers had access to personal transit or the help of hotel staff in case of trouble, middle-class visitors had nowhere to turn, especially if they lacked experience or didn’t know the language. Prepaid group tours allowed them to relax. An agent would meet them at the train station or the port, put them on transportation, pay for them, arrange guided tours, and accompany them at every destination.

Some agencies would also publish travel guide books. Thomas Cook’s books were specifically targeted at less urbane travelers of more average means, listing hotels, restaurants, and places of interest available to people of simpler tastes.

Cook’s travel books were meant to advertise an agency’s services

Source: Archive.org

Today, the appeal of traditional travel agencies remains the same, but the opportunities changed drastically. If in the 1920s people wanted to visit a foreign country, it was simply unsafe to try that alone. In 2020, we want independence and search for authentic experiences. We pack light, follow the advice of Instagram influencers, and get to enjoy long vacations combining beach gateways with work. Is there a way to make travel more convenient? The new decade will show.

1920 vs 2020

The futuristic city presented in 1927’s Metropolis is almost as far from our reality as it was to people 100 years ago. Would it disappoint time travelers from the past? It’s hard to predict how the innovations unfold, but we have at least some advances to boast about. In 2019, Qantas announced its testing of the longest flight in the world – 19 hours of travel between New York and Sydney. It seems like a lot, but it will also take less than a day – in the 1920s and for the decades to come, no ship or plane would have delivered you so fast across land and sea.

Comfort is another advancement though jet lag hasn’t gone anywhere. Prices are cheap even when they’re expensive and getting a ticket is so easy we can book a trip in a few clicks (a concept we would struggle to explain to our 1920s friends).

But the most fascinating parts are not the differences, but how much we have in common, even 100 years apart. It’s the wanderlust, the simple pull to grab a tent and go for a weekend getaway to the Grand Canyon. We are enchanted still by magical (albeit unrealistic) imagery of faraway places. We desire to expand our horizons, meet people around the world, experience new ways, foods, cultures. None of this will change in the next 100 years.

Canada Emigration and Immigration

Online Records [ edit | edit source ]

- Bef 1865Immigrants Before 1865 at Library and Archives Canada

- 1780-1906Canadian Immigrant Records, Part One at Ancestry ($)

- 1780-1906Canadian Immigrant Records, Part Two at Ancestry ($)

- 1789-1935Canada, Seafarers of the Atlantic Provinces, 1789-1935 at Ancestry ($) , index

- 1817-1896Canada, Immigration and Settlement Correspondence and Lists, 1817-1896 at Ancestry ($) , index/images

- 1819-1838Canada, St. Lawrence Steamboat Company Passenger Lists, 1819-1838 at Ancestry ($) , index/images

- 1832-1937Immigrants at Grosse Île Quarantine Station, 1832-1937 at Library and Archives Canada

- 1851-1872Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild Halifax, Nova Scotia, Ship arrivals and departures Index 1851-1872

- 1862-1897Canada, Ontario Immigration Records, 1862-1897 at FamilySearch – How to Use this Collection; index and images

- 1865-1935Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935 at Ancestry ($)

- 1865-1922Passenger Lists for the Port of Quebec City and Other Ports, 1865-1922 – at Library and Archives Canada

- 1865-1900Quebec City passenger lists, 1865-1900; index, 1865-1869, images.

- 1865-1883Toronto Emigrant Office Assisted Immigration Registers Database at the Archives of Ontario is an Index to four volumes of assisted immigration registers for the period 1865-1883 (Series RG 11-3). Over 29,000 entries in chronological order, the database is searchable by surname.

- 1865-1935Canada, Ocean Arrivals, 1865-1935 – Ancestry ($) , index and images.

- 1880-1899Passenger lists, 1880-1899, Halifax (Nova Scotia), images.

- 1881-1922Canada Passenger Lists, 1881-1922 at FamilySearch – index and images

- 1881Canada, British Vessel Crew Lists, 1881 at Ancestry ($) – index

- 1885-1949Canada, Registers of Chinese Immigration to Canada, 1885-1949 at FamilySearch – How to Use this Collection; index and images

- 1899-1949Immigrants to Canada, Porters and Domestics, 1899-1949 at Library and Archives Canada – index

- 1900-1922, 1925-1935Ships’ passenger lists for Canada, 1900-1922, 1925-1935, images.

- 1904-1954U.S., Records of Aliens Pre-Examined in Canada, 1904-1954 at Ancestry ($) – index/images

- 1908-1918Canada, Border Entry Lists, 1908-1918 at FamilySearch – How to Use this Collection; index & images

- 1912-1939U.S., Passenger and Crew Lists for U.S.-Bound Vessels Arriving in Canada, 1912-1939 and 1953-1962 at Ancestry ($) , index/images

- 1919-1924Canada, Ocean Arrivals (Form 30A), 1919-1924 at Ancestry ($) Also at FamilySearch, free.

- 1923-1933United States, Passenger Lists of Aliens Pre-Examined in Canada, 1906-1954 at FamilySearch — index and images

- 1823-1849Irish Canadian Emigration Records, 1823-1849 at Ancestry ($) , index and images.

- 1826Ireland, Parliamentary Papers on Emigration to Canada, 1826 at FamilySearch — index, images available through Findmypast

- 1919-1924Canada, Immigration Records, 1919-1924 at FamilySearch — How to Use this Collection; index & images

- 1929-1960Canada, Immigrants Approved in Orders in Council, 1929-1960 at Ancestry ($) , index/some images

- 1930-1965Immigrants to Canada 1930-1965, index

- 1953-1962U.S., Passenger and Crew Lists for U.S.-Bound Vessels Arriving in Canada, 1912-1939 and 1953-1962 at Ancestry ($) , index/images . Also at Canada, Ontario, Toronto Emigrant Office Records Index – Findmypast index ($) .

Border Crossings [ edit | edit source ]

- 1895-1956United States Border Crossings from Canada to United States, 1895-1956 at FamilySearch, index only. Includes records from seaports and railroad stations all over Canada and the northern United States.

- 1895-1960Border Crossings: From Canada to U.S., 1895-1960 at Ancestry, ($) .

- 1895-1954Vermont, St. Albans Canadian Border Crossings, 1895-1954. These list travelers to the United States from Canadian Pacific seaports only.

- 1905-1963Detroit Border Crossings and Passenger and Crew Lists, 1905-1963 at Ancestry, ($) .

- 1906-1954Michigan, Detroit Manifests of Arrivals at the Port of Detroit, 1906-1954. Only from Michigan ports of entry: Bay City, Detroit, Port Huron, and Sault Ste. Marie.

- 1908-1935Border Crossings: From U.S. to Canada, 1908-1935 at Ancestry, ($) , index and images. Some records in French. ($)

- 1908-1918Border port of entry lists for Canada, 1908-1918, images.

Cultural Groups Databases [ edit | edit source ]

- 1823-1849Irish Canadian Emigration Records, 1823-1849 at Ancestry ($) , index/images

- 1885-1949Immigrants from China, 1884-1949 at Library and Archives Canada – index

- 1898-1922Immigrants from the Russian Empire, 1898-1922, index

- 1899Names of Doukhobor immigrants to Canada in 1899, e-book.

- 1891-1930Ukrainian Immigrants, 1891-1930, index.

- 1929-1930Auswandererkartei der Rußlanddeutschen, 1929-1930 Index cards, arranged alphabetically by surname, for German-speaking emigrants from Russia to Germany, Canada, Brazil, Paraguay, etc. Includes original place of birth and residence, place of death of relatives, religion, emigration date, place of settlement, occupation, wife’s maiden name, marriage date and place, children’s names, names of relatives abroad and their places of residence, and documentary sources.

- 1946-1963Canada and U.S., Dutch Emigrants, 1946-1963 at Ancestry ($) , index/images , e-book.

Home Children [ edit | edit source ]

- 1869-1930Home Children, 1869-1930 at Library and Archives Canada – index

- 1880s-1916Home Children – Boards of Guardians at Library and Archives Canada – index

Loyalists [ edit | edit source ]

Military [ edit | edit source ]

Naturalization Records [ edit | edit source ]

-

, index and images. , index and images. , index and images.

Canada Offices to Contact [ edit | edit source ]

Library and Archives Canada [ edit | edit source ]

Library and Archives Canada

395 Wellington Street

Ottawa, ON K1A 0N3

Canada

Telephone: 613-996-7458

Fax: 613-995-6274

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [ edit | edit source ]

Before 1865 [ edit | edit source ]

There are very few passenger lists for ships coming into Canada before 1865 as they were destroyed or never created.

Substitute records have been used to help document individuals coming to Canada during this time but are very incomplete. They include declarations of aliens and other naturalization records, diaries, newspaper articles, and other records indicating immigration to Canada.

The Library and Archives of Canada website has posted an index of some lists that have survived. Other databases containing information suggesting immigration are found in the Online Records section above.

1865 to 1935 [ edit | edit source ]

Passenger lists are available for ports in Canada starting in 1865. Many records are online and can be found in the Online Records section above.

Most immigrants to Canada arrived at the ports of Quebec and Halifax, although many came to New York and then traveled to Canada by way of the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and Great Lakes. A few arrived in Portland, Maine, then traveled overland to Canada. Surviving lists for Quebec date from 1865 and for Halifax from 1881.

After 1935 [ edit | edit source ]

Library and Archives Canada does not hold copies of post-1935 records. Records of immigrants arriving at Canadian land and seaports from January 1, 1936 onwards remain in the custody of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. To request a copy of another person’s immigration record, you must mail a signed request to the under-noted office:

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC)

Access to Information and Privacy Division

Ottawa, ON K1A 1L1

Canada

- The request should include the full name at time of entry into Canada, date of birth and year of entry. Additional information is helpful, such as country of birth, port of entry and names of accompanying family members.

- The application for copies of records should indicate that it is being requested under Access to Information. It must be submitted by a Canadian citizen or an individual residing in Canada. For non-citizens, you can hire a free-lance researcher to make the request on your behalf. The request must be accompanied by a signed consent from the person concerned or proof that he or she has been deceased for 20 years. Please note that IRCC requires proof of death regardless of the person’s year of birth.

- Fee: $5.00 (by cheque or money order made payable to the Receiver General for Canada) [1]

Finding the Town of Origin in Canada [ edit | edit source ]

If you are using emigration/immigration records to find the name of your ancestors’ town in Canada, see Canada Finding Town of Origin for additional research strategies.

Canada Emigration and Immigration [ edit | edit source ]

“Emigration” means moving out of a country. “Immigration” means moving into a country.

Emigration and immigration sources list the names of people leaving (emigrating) or arriving (immigrating) in the country. These sources may be passenger lists, permissions to emigrate, or records of passports issued. The information in these records may include the emigrants’ names, ages, occupations, destinations, and places of origin or birthplaces. Sometimes they also show family groups.

Immigration into Canada [ edit | edit source ]

Most immigrants have settled along the coasts, the southern frontiers, or the St. Lawrence River valley.

1605: The French first settled at Port Royal, near present Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.

1608: The city of Quebec was established by the French. For the next 150 years, the British and the French disputed control of the area.

‘1749: ‘Halifax, Nova Scotia, was founded by the British as a military garrison.

1753: The British government settled more than 1,400 Germans and Swiss at Lunenburg, southwest of Halifax.

1759–1760: British conquest of old Quebec (New France) occurred. The French remained but were joined by many British immigrants.

1760: Eighteen hundred “planters” from Rhode Island and Connecticut settled lands vacated by Acadians in Nova Scotia. A few thousand more New Englanders and Ulster Irish soon followed.

1783–1784: More than 30,000 Loyalist refugees came to Canada as a result of the American Revolution. They settled in the Maritime Provinces, the Eastern Townships section of Quebec, and in the area between the Ottawa and St. Lawrence river valleys, eventually to be called Upper Canada. The Loyalists were soon followed by other Americans coming for land.

1800: Upper Canada (Ontario) had about 35,000 people, including 23,000 Loyalists and “late Loyalists” and their descendants, mainly from upstate New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. They were principally established on farms along the upper St. Lawrence River valley.

1812: Because of the War of 1812, authorities restricted immigration from the United States and encouraged immigration from the British Isles.

1815: After the close of the Napoleonic wars in Europe, many immigrants settled along the St. Lawrence River. Although many immigrants continued on to the United States, soon the “late Loyalists” were joined by many English, Scottish, and Irish settlers.

1815–1850: Greatest immigration was from Scotland and Ireland to Atlantic colonies. A few thousand came each year.

1818: The influx of Protestant Irish to Upper Canada began in earnest.

1830s: The great Irish immigration took place, especially to New Brunswick.

1846–1850s: During the Famine Migration from Ireland, tens of thousands settled farms and towns of Upper and Lower Canada.

1881: A record number of people immigrated; many headed for Manitoba. The best Manitoba farmland was settled by people from Ontario.

1890s: The boom era began in western Canada because much of the best public land in United States had already been homesteaded.

1896–1914: The Canadian government’s aggressive immigration policy encouraged agricultural settlers from Britain, then the United States. Canadian colonization agents at the seaports of Hamburg and Bremen recruited Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Austro-Hungarians.

1900s: The early 1900s were the peak of U.S. immigration to Canada.

1931: The 1931 census showed 1,300,000 U.S.-born residents settled throughout Canada: over 12 percent of the population.

Loyalists [ edit | edit source ]

Beginning in 1784, large numbers of American Loyalists came from the United States to settle along the St. Lawrence River. Most of the earliest settlers of Upper Canada (Ontario) were natives of the United States. By 1810, eighty percent of the white population of the province was estimated to have been born in the U.S., but only 25 percent of them were Loyalists (who had arrived by 1796) or their descendants. The rest were Americans who had recently come to Canada for land or other economic opportunities. New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania were listed as states of origin of many of these “late Loyalists,” as they were sometimes called.

British Home Children Immigrants 1870-1940 [ edit | edit source ]

Between 1869 and the late 1930s, over 100,000 juvenile migrants were sent to Canada from the British Isles during the child emigration movement.

- 1869-1930Home Children, 1869-1930 at Library and Archives Canada – index

- 1880s-1916Home Children – Boards of Guardians at Library and Archives Canada – index

War Brides [ edit | edit source ]

During World War II, Canadian soldiers began arriving in Britain as early as 1939. For some it would be six years before they returned home. Many of these young men married and fathered children while they were overseas. In all, nearly 48,000 war brides and 22,000 children arrived in Canada during and after World War II. While the vast majority of these women were British, there were some Europeans as well. The ships that had been used to transport the service men and women to Britain returned with their wives and children. The ships carrying the war brides and their children sailed from England to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Pier 21 became the depot for processing the arriving families. In 2000. a memorial plaque was mounted at Pier 21 to commemorate the war brides’ a

Emigration from Canada [ edit | edit source ]

- The first large emigration from Canada was between 1755 and 1758 when 6,000 French Acadians were deported from Nova Scotia. Some settled temporarily in other American colonies and in France. Many eventually found permanent homes in Louisiana, where they were called “Cajuns.” A few returned to the Maritime Provinces.

- During the “Michigan Fever”‘ of the 1830s, large numbers of Canadians streamed westward across the border. About one in four Michigan families finds a direct connection to Ontario.

- By the late 1840s, over 20,000 Canadians and newly landed foreign immigrants moved to the United States each year. * TheCalifornia Gold Rush attracted many, beginning in 1849.

- After 1850, the tide of migration still flowed from Canada to the United States. Newly arrived immigrants tended not to stay in Canada very long. Between 1851 and 1951, there were up to 80 emigrants, both natives of Canada and others, who left Canada for every 100 immigrants who arrived. A few immigrants returned to their native lands or went elsewhere, but many eventually went to the United States after brief periods of settlement in Canada.

- Canadians from the Atlantic Provinces often went to New England. At least two million descendants of French Canadians now live in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Many also live in New York and the Midwestern states.

- The Canadian government did not keep lists of emigrants. Before 1947, there was no Canadian citizenship separate from British, and Canadians moved freely throughout the British Empire. Before 1895, when the United States government began keeping border-crossing records, Canadians moved to the United States with few restrictions.

- Most immigrants to Canada arrived at the ports of Quebec and Halifax, although many came to New York and then traveled to Canada by way of the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and Great Lakes. A few arrived in Portland, Maine, then traveled overland to Canada.

Canadian Diaspora [ edit | edit source ]

The Canadian diaspora is the group of Canadians living outside the borders of Canada. As of a 2010 report by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada and The Canadian Expat Association, there were 2.8 million Canadian citizens abroad (plus an unknown number of former citizens and descendants of citizens). In past decades, most Canadians leaving the country have moved to the United States. In the 1980s, Los Angeles had the fourth largest Canadian population of any city in North America, with New York close behind. Other countries and cities have emerged as major sites of Canadian settlement, notably Hong Kong, London, Beirut, Sydney, Paris, and Dubai. The largest Canadian populations abroad by country are: [2]

Travelling to Europe From US: What Travellers Must Know

This tourist season may have been mesmerizing for many Americans who chose European countries in order to spend some holidays after a year in lockdown.

Yet, those who postponed their trip to Europe for the end of summer and beyond may have to wait a little bit longer, in particular, if they haven’t been vaccinated yet as some European countries have started to ban non-essential travel for arrivals from the United States after the latter reported a surge in the number of COVID-19 infections.

Besides being profoundly affected by the Delta variant, the new COVID-19 variant known as Mu has been detected in 49 US States up to this point.

Therefore authorities in some European countries have decided to implement additional preventive measures in order to stop another COVID-19 epidemic wave.

EU Council Has Already Recommended to the Member States to Tighten Entry REstrictions for Americans

All travellers from the United States welcomed the Council of the European Union decision of June 18 when the US was included in the list of countries considered safe based on the rate of COVId-19 infections.

From June 18, travellers from the US were permitted to enter the majority of EU countries, restriction-free, even for non-essential purposes such as tourism.

However, last week, on August 30, the Council removed the United States together with five other countries from the safe list, urging its Member States to impose stricter entry rules for Americans and ban non-essential travel. Soon after the Council made its recommendation public, European countries started to make their position clear regarding the EU advice.

While some of them followed the Council’s advice, some other states clarified that they would not take such a step as the recommendation is not legally binding.

Before travelling to Europe, American travellers must know whether European countries implemented the EU Council recommendation or not.

Which EU Countries Have Applied the EU Recommendation & Which Have Refused to Do So?

On September 1, Bulgaria included the United States in its red list that consists of countries highly affected by the virus. Thus, regardless of their vaccination status, US travellers are banned from entering Bulgaria unless for specific exceptional cases.

Encouraged by the EU advice, authorities in Denmark also prohibited the entry for arrivals from the US as of September 6. However, authorities in Denmark emphasized that US travellers wishing to enter Denmark for essential purposes would be allowed to do so.

In an effort to stop the further spread of the virus, the Swedish government announced stringent entry requirements for Americans. However, authorities in Sweden announced that travellers wishing to enter the Scandinavian country for essential purposes would not be affected by the recent changes.

Regardless of their vaccination status, travellers from the US are also banned from entering Norway. As for the Netherlands, since September 6, Americans are required to present a recent negative result of the Coronavirus test and follow a ten-day self-isolation requirement upon their arrival in the Netherlands.

SchengenVisaInfo.com yesterday reported that Spain banned the entry of non-vaccinated travellers from the US, unless for emergency purposes, upon the recommendation of the Council of the EU to make such a step. The decision was confirmed by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare.

Due to the Coronavirus situation in the United States, Belgium and Germany imposed stricter entry rules for US arrivals before the Council recommendation.

However, other European countries, such as Greece, Croatia, Iceland, Portugal and Ireland, refused to impose stricter entry rules for arrivals from the US, despite the latter being profoundly affected by the virus, especially from the Delta variant.

“EU recommendation is non-binding, and the Member States retain control over their own border restrictions,” the Irish government stressed through a statement.

Authorities in Greece, Croatia, Iceland, Ireland, and Portugal refused to impose stricter entry rules for arrivals from the United States, despite the latter being profoundly affected by the virus, especially from the Delta variant.

Travelling to Europe As a Vaccinated US Citizen

Vaccinated travellers from the US are permitted to enter most of the European countries provided they have been fully vaccinated, except Bulgaria and Norway that have banned the entry even for vaccinated Americans.

Most European countries accept as valid proof of immunity vaccines that are approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), such as:

- Pfizer/BioNTech (Comirnaty)

- AstraZeneca EU (Vaxzevria)

- Moderna (Spikevax)

- Johnson & Johnson (Janssen)

However, European countries are permitted to individually decide whether they want to accept other vaccines that are not approved by EMA or not.

Are Vaccinated US Residents Obliged to Present Negative Result of COVID-19 Test

Despite being vaccinated against the Coronavirus, travellers from the US must prove that they have recently tested negative for the virus in several EU countries. For example, authorities in Germany, Iceland and Italy, oblige US arrivals to present a negative result of the COVID-19 test, not older than 72 hours, upon arrival.

Are Americans Obligated to Quarantine Anywhere in Europe

The Netherlands imposes among the strictest restrictions for Americans. While the country permits only fully vaccinated US travellers, they must also follow the compulsory quarantine requirement.

As per non-vaccinated travellers, they are permitted to in many EU countries; however, they must follow strict entry rules. For example, unvaccinated US travellers planning to head to the Czech Republic, Ireland, Iceland, Estonia, Slovakia, Italy, and Romania must follow mandatory self-isolation requirements.

Health Insurance Remains a Must Even for American Travellers to EU

Travellers from the US planning to travel to Europe any time soon are urged to purchase travel insurance in order to be protected during their trip.

Travel insurance can help them save most of the money if the trip gets cancelled due to the COVID-19 situation or other similar reasons. Besides, if passengers get sick or suffer an accident during their trip, travel insurance will cover all the medical treatment costs.

Passengers can purchase reasonably priced travel insurance in European countries from AXA Assistance or Europ Assistance.

What Is Open for Visitors in Europe

Despite the upsurge in the number of COVID-19 infections, vaccinated travellers from the United States can pack their suitcase and head to some of Europe’s most famous places, even for tourism, including countries like Ireland, Iceland, Croatia, Portugal, and France, provided they follow carefully the requirements imposed by local authorities due to the COVID-19 situation.

Current COVID-19 situation in the US & the US Travel Ban on Europe

Even though WHO’s figures show that the US has a marked total of 39,893,580 cases according to data provided by the New York Times, the number of COVID-19 infections in the United States has already surpassed 40 million cases.

Whereas so far, 53 per cent of the American population have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Source https://www.altexsoft.com/blog/travel-in-the-1920s/

Source https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Canada_Emigration_and_Immigration

Source https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/travelling-to-europe-from-us-what-travellers-must-know/