Jonathan Swift and Gulliver s Travels

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift: Summary and Analysis

Kama Offenberger has taught English in colleges and universities for over 15 years. She has a Master’s degree in English from Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University.

Patricia has an MFA in Writing, an MS in Teaching and English Language Arts, and a BA in English.

Explore Jonathan Swift’s ‘Gulliver’s Travels.’ Read about the author, meet the characters, study the summary and analysis, and review Gulliver’s islands and Laputa. Updated: 05/10/2022

Table of Contents

Gulliver’s Travels

While it has been viewed by many as a fantastical adventure novel or silly children’s book, Gulliver’s Travels is a complex political satire. Originally published on October 28, 1726, this well-known novel by Jonathan Swift was intended as a parody of the travel narratives that were so popular at the time. It also depicts prominent political figures and parties of the time, questions morality and the concept of individuality, and examines the concept of the ideal society.

Who Wrote Gulliver’s Travels?

The author of Gulliver’s Travels was Jonathan Swift, an Irish writer who is generally regarded as one of the most talented satirists in literature. Although he is best known for his writing, Swift was also a member of the clergy.

Swift’s first book, A Tale of a Tub, was well-received, but it was Gulliver’s Travels that contributed most to his reputation as a satirist. Gulliver’s Travels, his most famous work, was published in response to the prevalence of travel narratives and what Swift perceived as offensive and questionable behavior by those in authority. It garnered immediate and enormous success, becoming so popular, in fact, that it has never been out of print since its first run in 1726.

Swift was also outspoken in his criticism of the government, particularly in the treatment of Irish Catholics by the British. This was the focus of A Modest Proposal, which was both polarizing and immensely intriguing upon its publication in 1729. Though his later writings continued his biting social commentary, none reached his prior level of success. In 1742, Swift suffered a stroke and lost the ability to speak, and he died on October 19, 1745.

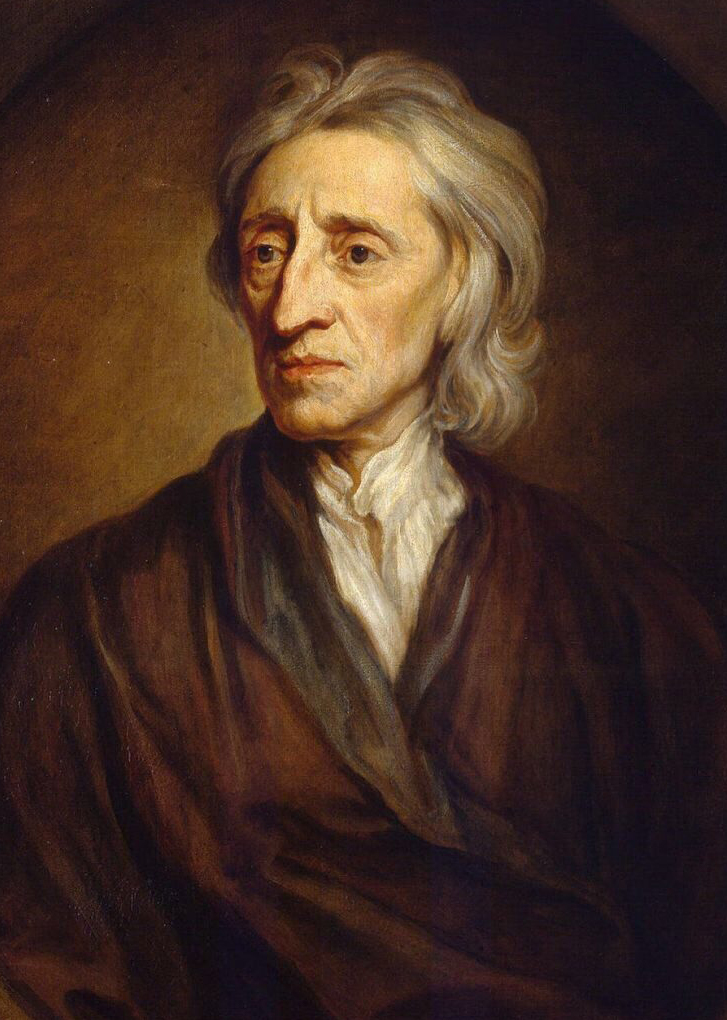

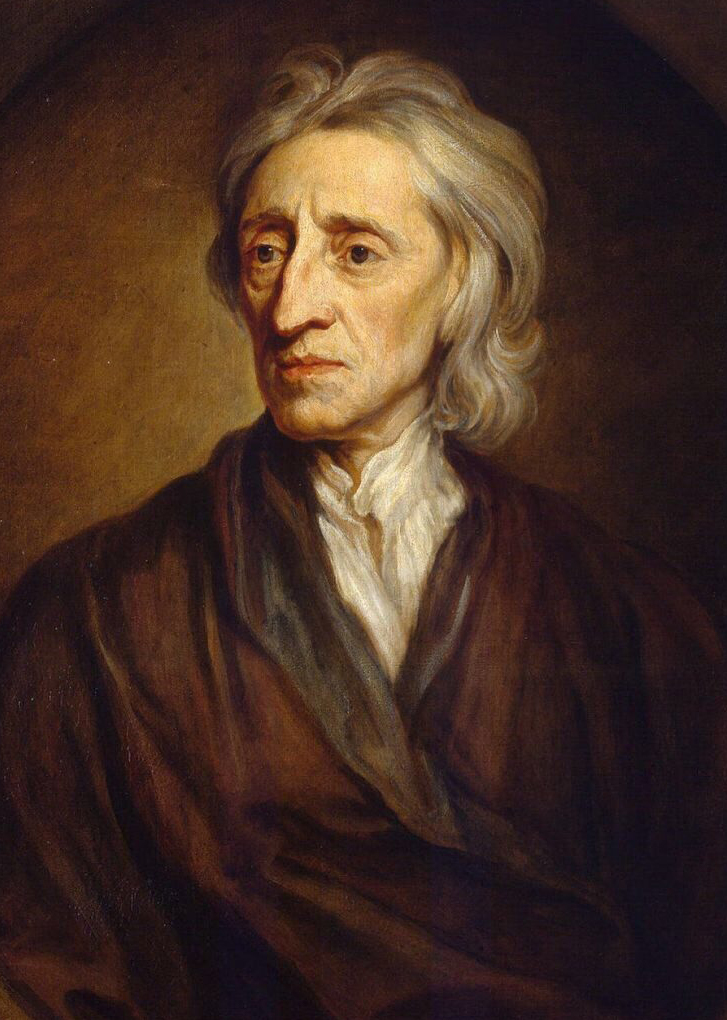

Jonathan Swift is widely regarded as one of the greatest satirists in the history of English literature.

Who Is Gulliver?

Written by Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels is the story of the adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, the narrator and protagonist of the story. Gulliver is a married surgeon from Nottinghamshire, England, who has a taste for traveling. He works as a surgeon on ships and eventually becomes a ship captain.

Through one unfortunate event at sea to the next, Gulliver finds himself stranded in foreign lands and absurd situations, from being captured by the miniature Lilliputians to befriending talking horses, the Houyhnhnms. Although Gulliver’s vivid and detailed storytelling makes it clear that he is intelligent and well-educated, his perceptions are naïve and gullible. Gulliver never thinks that the absurdities he encounters are funny, and never makes the satiric connections between the lands he visits and his own home.

An error occurred trying to load this video.

Try refreshing the page, or contact customer support.

You must c C reate an account to continue watching

Register to view this lesson

As a member, you’ll also get unlimited access to over 84,000 lessons in math, English, science, history, and more. Plus, get practice tests, quizzes, and personalized coaching to help you succeed.

Get unlimited access to over 84,000 lessons.

Already registered? Log in here for access

Resources created by teachers for teachers

I would definitely recommend Study.com to my colleagues. It’s like a teacher waved a magic wand and did the work for me. I feel like it’s a lifeline.

You’re on a roll. Keep up the good work!

Just checking in. Are you still watching?

Want to watch this again later?

Log in or sign up to add this lesson to a Custom Course.

Characters in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

The list of characters in Gulliver’s Travels is extensive, and it can be confusing because of the unique names that Swift applied to individuals and groups.

| Location | Specific Characters | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|

| England | Lemuel Gulliver | Gulliver is both the protagonist and narrator as well as the only well-developed character in the book. As the son of a middle-class English family, he is a practical man who studied medicine, but, when his business fails, he decides to leave England and travel in search of other lands. |

| Lilliput | Emperor | The Lilliputians are tiny beings, around six inches tall. The emperor’s governing practices are ridiculous in that he selects high court officials based on their rope dancing skills. He is intended as a representation of the King of England at the time, George I. |

| Blefuscu | Blefuscudians | The creatures of Blefuscu are the enemies of the Lilliputians, who disagree with them about the proper way to crack eggs. |

| Brobdingnag | Farmer, King, and Queen | In contrast to the Lilliputians, the Brobdingnag are giants. The farmer who initially discovers Gulliver keeps him for a time as a sort of animal before selling him to the queen. The king asks Gulliver to teach him about English governance and is appalled to find that it is a system overcome with hypocrisy, bribery and corruption. |

| Laputa | Laputans | The island of Laputa in Gulliver’s Travels is home to academics who are completely engrossed in their thoughts. |

| Houyhnhnm Land | Houyhnhnms and Yahoos | Completely cut off from the rest of the world, the Houyhnhnms are a race of intelligent horses. They share the island with their servants, the Yahoos, human-like beasts that Gulliver finds repellent. |

The Yahoos are the horrible creatures that Gulliver discovers are much like him.

Gulliver’s Travels Summary

A pragmatic surgeon, Lemuel Gulliver leaves his family in England when his business fails. Told from a first-person perspective, the novel details his journey and is separated into four sections, each best distinguished by the land that he visits. The mysterious countries and islands of Gulliver’s Travels provide him with a new perspective on humanity.

Lilliput

After being shipwrecked, Gulliver wakes to discover that he has been bound by the Lilliputians, who are only about six inches tall. He is eventually taken to the capital city and presented to the emperor, who finds him entertaining. The emperor tries to use Gulliver as a weapon against the people of Blefuscu, another group of miniature people and sworn enemies of the Lilliputians. The two groups are at war because of a disagreement about the way to crack eggs. After a time, Gulliver is convicted of treason for putting out a fire in the royal palace with his urine. He escapes to Blefuscu, where he is able to repair his boat and return to England.

Brobdingnag

After a two-month stay in England, Gulliver travels to Brobdingnag, a land of 60-foot giants. He is initially discovered by a farmer, who treats him much like an animal before selling him to the queen to be used as entertainment at court. The king asks that Gulliver teach him about the governance of England, but he is then horrified when he discovers. that there is no protection against corruption. Meanwhile, Gulliver is disgusted by the Brobdingnags because their enormous size magnifies all of their flaws. Eventually, while traveling with the queen, an eagle picks up his cage and drops it into the sea, fostering his escape.

Laputa

Gulliver sets sail once more, but this time he is attacked by pirates and finds himself on an island inhabited by theoreticians and academics. He discovers that, in spite of their great intellect, the research of the Laputans is in no way useful for common people. Engrossed in their own intelligence, the Laputans have to be shaken out of their meditations by the flappers, servants who shake rattles in their ears. After leaving Laputa, Gulliver makes a brief stop in Glubbdubdrib, where he has the opportunity to witness historic icons like Julius Caesar, whom he finds far less impressive than books had led him to believe. He also comes visits the Luggnaggians and Struldbrugs, immortals who are completely senile, proving that the adage that age brings wisdom is untrue. Finally, he sails to Japan and back to England.

Land of the Houyhnhnms

The final expedition in Gulliver’s journey brings him to an unknown land off the coast of Australia. This country is ruled by the Houyhnhnms, rational and community-based horses, whose servants, the Yahoos, are repulsive creatures quite similar to humans. Of all the places Gulliver visits, he is most content in Houyhnhnms, and he learns their language so that he can tell them about his voyage and his home country of England. The Houyhnhnms are fascinated by his stories, and Gulliver hopes to stay on the island. However, once his body is exposed without clothing, they discover his remarkable similarities to the Yahoos and banish him from their land. Heartbroke, he builds a canoe that he takes to a nearby island, where he is picked up by a Portuguese ship and eventually returned to England. His travels have changed him, leaving him longing to return to the Houyhnhnms and unable to distinguish all people from the beast-like Yahoos, so he leaves his family and lives in isolation.

Analysis of Gulliver’s Travels

The success of Gulliver’s Travels rests not only in its fantastical imaginings but also in its deft use of parody and satire. For example, while the Houyhnhnms may be talking horses, they are also representative of traits that Swift finds lacking in the leaders and politicians of the time.

In general, the message behind Gulliver’s Travels appears to be one of condemnation. Within the novel, Swift ridicules learning without practical purpose, speaks out against war, and mocks the sin of greed. He also, however, emphasizes those strengths that he believes might make society a better place, including friendship, loyalty, humility, and kindness. Whether Swift intends for the reader to see these virtues as achievable by humankind is unclear, particularly as Gulliver himself lacks humility at the end of the novel, but he nevertheless indicates that they are worth pursuing.

King George I of England was a prime target among the many political figures parodied by Swift.

Themes of Gulliver’s Travels

There are many distinguishable themes in Gulliver’s Travels, but some appear more consistently than others.

The first identifiable theme is the debate between moral righteousness and physical strength and which should be prioritized in governance. Swift’s answer is ambiguous, as Gulliver finds himself in the position of being both physically dominant with the Lilliputians and incredibly vulnerable with the Brobdingnags. Likewise, the conflict between the Lilliputians and Blefuscudians is one based on morality, but the argument is fundamentally ridiculous. This indicates that neither physical strength nor morality is preferable as a governing principle, particularly as they can both be corrupted to serve the interests of those in power.

Another important theme is the examination of individuality in comparison to communal society. In other words, the novel represents both societies that promote individualism and those that focus on the greater good, and it is reasonable to wonder which he is arguing is the better model. Again, Swift does not attempt to definitively resolve this issue. He parodies the excesses of communal living with groups like the Houyhnhnms, who have become so unified that there is almost no distinction between them. However, he also demonstrates the danger of isolation and pure individuality, particularly through Gulliver’s grief and longing after being forced to leave the Houyhnhnms behind.

Much of the plot of Gulliver’s Travels is fueled by deception and secrecy. Gulliver is frequently deceptive, including when he lies to the Houyhnhnms, claiming that his clothes are part of his body so that they will not equate him with the Yahoos. Similarly, the Lilliputians develop a secret plot to starve Gulliver. There is a general condemnation of lying within the novel, which is underscored by the fact that the land Gulliver likes best, that of the Houyhnhnms, is one in which there is absolute honesty to such a degree that they do not even have a word for mistruths.

Lesson Summary

Jonathan Swift‘s intensely popular and oft-studied novel Gulliver’s Travels was originally published in 1726. It was intended as a parody of travel narratives as well as a satirical commentary on the politicians and government of the time, including King George I. Within his novel, Swift examines several important concepts, including the dynamic of physical power and moral righteousness, the value of individualism in comparison to communal society, and the dangers of deception and secrecy. The story examines these ideas through the adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, a practical man from England who has decided to travel the seas. On his journey, he encounters many interesting beings and learns about their beliefs and forms of government.

The first group Gulliver discovers are the miniature people called the Lilliputians. They are at war with another group of tiny people from Blefuscu because of a disagreement about the proper way to eat eggs. He next goes to Brobdingnag, a place occupied by giants who use Gulliver as a form of entertainment until he finally escapes when his cage is picked up by an eagle and dropped into the sea. Following this experience, Gulliver visits Laputa, which is home to a group of academics who are so consumed by their intellectual reveries that they have to be shaken free of their thoughts. Finally, he finds himself a land he actually enjoys, that of the Houyhnhnms, who are intelligent horses with human-like servants called the Yahoos. In the end, Gulliver is banished and left in despair as he cannot distinguish people from the Yahoos and desperately wishes to be back with the Houyhnhnms.

Lilliput

Gulliver’s adventures begin in Lilliput, when he wakes up after his shipwreck to find himself bound by the tiny threads of the Lilliputians, a civilization of miniature people fewer than six inches tall. They shout at him and poke him with their tiny arrows, and then construct a wagon to carry him into the capital city to present him to the emperor.

The emperor decides to keep Gulliver captive, spending a fortune to feed him. Because of his tiny size, his belief that he can control Gulliver seems silly, but his willingness to execute his subjects for minor reasons of politics or honor gives him a frightening aspect. The emperor decides to use Gulliver as a weapon in the war against the Blefuscu, another society of tiny people whom the Lilliputians hate because of perceived differences concerning the proper way to eat eggs. Lilliputians and Blefuscudians are prone to conspiracies and jealousies, and are quick to take advantage of Gulliver in political intrigues of various sorts.

A fire breaks out in the royal palace, and Gulliver extinguishes the fire by urinating on it. As a result of having urinated on the royal palace, he is tried and convicted of treason and sentenced to be shot in the eyes and then starved to death. But, he escapes to Blefuscu, where he finds a boat, is able to repair it, and sets sail for home, England.

Brobdingnag

After staying in England with his wife and family for two months, Gulliver sets off on his next adventure, which takes him to a land called Brobdingnag, populated by giants about 60 feet tall called Brobdingnagians. Here, he is found by a farmer, who puts him in a cage and displays him around Brobdingnag. His exploitation of him as a laborer nearly starves Gulliver to death, and the farmer decides to sell him to the queen, who he must entertain with his musical talents.

The queen of Brobdingnag is so delighted by Gulliver’s beauty and charms that she agrees to buy him from the farmer for 1,000 pieces of gold. The queen seems to care about her new pet, asking Gulliver whether he would consent to live at court and inquiring as to the reasons for his cold goodbyes to the farmer. The queen employs a teacher and caretaker for Gulliver, a girl named Glumdalclitch, who affectionately tends to him throughout his adventures in Brobdingnag.

The king of Brobdingnag, in contrast to the emperor of Lilliput, is well-versed in political science. The king’s relationship with Gulliver is limited to serious discussions about the history and institutions of Gulliver’s native England. Though at one point, the king dismisses him and refers to the English as odious vermin. Gulliver does not escape his captors and their ill treatment until the king and queen decide to take him on a trip, and his cage is plucked up by an eagle and dropped into the sea, where he manages to find his ship and sail back to England.

Laputa and Other Islands

After another two months with his family, Gulliver sets sail again and gets marooned by pirates on a small island. As he’s sitting on this island, he sees a shadow passing overhead. It is a floating island called Laputa, inhabited by Laputans, theoreticians and academics who rule over the land below, called Balnibarbi. He signals them for help and is brought up by rope.

Here, the inhabitants are impractical and out of touch with reality, often engaging in inane research and ruining their farms and buildings with newfangled reforms. The Laputans are so inwardly absorbed in their own thoughts that they must be shaken out of their meditations by special servants called flappers, who shake rattles in their ears.

Gulliver also visits Glubbdubdrib, an island of sorcerers, where he gets to meet the ghosts of famous historical figures, and Luggnagg, an island with an absolute king who rules over a population of senile immortals. Eventually, he makes his way to Japan and then sails back to England once more, this time for five months, before he sets out again.

Houyhnhnm Land

On his fourth and final adventure, Gulliver sails out as a captain in his own right. But his sailors mutiny against him and maroon him on a distant island, Houyhnhnm Land. This island is populated by rational-thinking horses, called Houyhnhnms.

The Houyhnhnms maintain a simple, peaceful society governed by reason and truthfulness, and they do not even have a word for ‘lie’ in their language. They are the masters of the Yahoos, brutish, unkempt humanlike creatures who are not capable of government and are kept as servants to the Houyhnhnms, pulling their carriages and performing manual tasks.

It is through the Houyhnhnms that Gulliver is led to re-evaluate the differences between humans and animals and to question humanity’s claims to rationality. Gulliver learns the Houyhnhnms’ language and spends many satisfying hours in conversation with them, so much so that when they tell him he must leave, he is devastated.

He leaves obediently, knowing that it is his resemblance to the Yahoos that is at the heart of it; they are just like him, except that Gulliver has learned to clip his nails, shave his face, and wear clothes. He makes a canoe and paddles to a nearby island, where he is picked up by a Portuguese ship that returns him to England and his family. Once Gulliver returns to his family, however, he can only see them as brutish Yahoos. He can barely stand to be in the same room with them. He longs for the Houyhnhnms and spends at least four hours a day talking to his two stallions in their stable.

Lesson Summary

Gulliver’s Travel’s, written by Jonathan Swift, recounts in first-person narrative the vibrant adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, a surgeon who works on ships and time after time encounters himself stranded in new lands, a victim of shipwreck, piracy, and mutiny.

In Lilliput, he’s taken captive by the Lilliputians, miniature people less than six inches tall, where the emperor is surprisingly able to control him until his escapes from Blefuscu. In his following adventure, he’s enslaved by a giant civilization and becomes a figure of entertainment, first by an exploiting farmer and then by the queen and king of Brogdingnab.

Subsequently, he visits the floating island of Laputa, populated by absurd, self-absorbed scientists. On his final adventure to Houyhnhnm Land, he befriends a peaceful civilization of horses who rule over the brutish, humanlike Yahoos. After learning the ways of the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver is unable to adjust to living in society, since he can only view the English like they are Yahoos.

Learning Outcomes

Once you’re through with the lesson, you should be able to:

- Recall who Gulliver is from Gulliver’s Travels

- Explain the importance of Lilliput

- Describe Brobdingnag and the characters Gulliver meets there

- Consider the importance of Laputa and other islands and the inhabitants there

- Recall his adventures to Houyhnhnm

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member.

Create your account

Who Is Gulliver?

Written by Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels is the story of the adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, the narrator and protagonist of the story. Gulliver is a married surgeon from Nottinghamshire, England, who has a taste for traveling. He works as a surgeon on ships and eventually becomes a ship captain.

Through one unfortunate event at sea to the next, Gulliver finds himself stranded in foreign lands and absurd situations, from being captured by the miniature Lilliputians to befriending talking horses, the Houyhnhnms. Although Gulliver’s vivid and detailed storytelling makes it clear that he is intelligent and well-educated, his perceptions are naïve and gullible. Gulliver never thinks that the absurdities he encounters are funny, and never makes the satiric connections between the lands he visits and his own home.

Lilliput

Gulliver’s adventures begin in Lilliput, when he wakes up after his shipwreck to find himself bound by the tiny threads of the Lilliputians, a civilization of miniature people fewer than six inches tall. They shout at him and poke him with their tiny arrows, and then construct a wagon to carry him into the capital city to present him to the emperor.

The emperor decides to keep Gulliver captive, spending a fortune to feed him. Because of his tiny size, his belief that he can control Gulliver seems silly, but his willingness to execute his subjects for minor reasons of politics or honor gives him a frightening aspect. The emperor decides to use Gulliver as a weapon in the war against the Blefuscu, another society of tiny people whom the Lilliputians hate because of perceived differences concerning the proper way to eat eggs. Lilliputians and Blefuscudians are prone to conspiracies and jealousies, and are quick to take advantage of Gulliver in political intrigues of various sorts.

A fire breaks out in the royal palace, and Gulliver extinguishes the fire by urinating on it. As a result of having urinated on the royal palace, he is tried and convicted of treason and sentenced to be shot in the eyes and then starved to death. But, he escapes to Blefuscu, where he finds a boat, is able to repair it, and sets sail for home, England.

Brobdingnag

After staying in England with his wife and family for two months, Gulliver sets off on his next adventure, which takes him to a land called Brobdingnag, populated by giants about 60 feet tall called Brobdingnagians. Here, he is found by a farmer, who puts him in a cage and displays him around Brobdingnag. His exploitation of him as a laborer nearly starves Gulliver to death, and the farmer decides to sell him to the queen, who he must entertain with his musical talents.

The queen of Brobdingnag is so delighted by Gulliver’s beauty and charms that she agrees to buy him from the farmer for 1,000 pieces of gold. The queen seems to care about her new pet, asking Gulliver whether he would consent to live at court and inquiring as to the reasons for his cold goodbyes to the farmer. The queen employs a teacher and caretaker for Gulliver, a girl named Glumdalclitch, who affectionately tends to him throughout his adventures in Brobdingnag.

The king of Brobdingnag, in contrast to the emperor of Lilliput, is well-versed in political science. The king’s relationship with Gulliver is limited to serious discussions about the history and institutions of Gulliver’s native England. Though at one point, the king dismisses him and refers to the English as odious vermin. Gulliver does not escape his captors and their ill treatment until the king and queen decide to take him on a trip, and his cage is plucked up by an eagle and dropped into the sea, where he manages to find his ship and sail back to England.

Laputa and Other Islands

After another two months with his family, Gulliver sets sail again and gets marooned by pirates on a small island. As he’s sitting on this island, he sees a shadow passing overhead. It is a floating island called Laputa, inhabited by Laputans, theoreticians and academics who rule over the land below, called Balnibarbi. He signals them for help and is brought up by rope.

Here, the inhabitants are impractical and out of touch with reality, often engaging in inane research and ruining their farms and buildings with newfangled reforms. The Laputans are so inwardly absorbed in their own thoughts that they must be shaken out of their meditations by special servants called flappers, who shake rattles in their ears.

Gulliver also visits Glubbdubdrib, an island of sorcerers, where he gets to meet the ghosts of famous historical figures, and Luggnagg, an island with an absolute king who rules over a population of senile immortals. Eventually, he makes his way to Japan and then sails back to England once more, this time for five months, before he sets out again.

Houyhnhnm Land

On his fourth and final adventure, Gulliver sails out as a captain in his own right. But his sailors mutiny against him and maroon him on a distant island, Houyhnhnm Land. This island is populated by rational-thinking horses, called Houyhnhnms.

The Houyhnhnms maintain a simple, peaceful society governed by reason and truthfulness, and they do not even have a word for ‘lie’ in their language. They are the masters of the Yahoos, brutish, unkempt humanlike creatures who are not capable of government and are kept as servants to the Houyhnhnms, pulling their carriages and performing manual tasks.

It is through the Houyhnhnms that Gulliver is led to re-evaluate the differences between humans and animals and to question humanity’s claims to rationality. Gulliver learns the Houyhnhnms’ language and spends many satisfying hours in conversation with them, so much so that when they tell him he must leave, he is devastated.

He leaves obediently, knowing that it is his resemblance to the Yahoos that is at the heart of it; they are just like him, except that Gulliver has learned to clip his nails, shave his face, and wear clothes. He makes a canoe and paddles to a nearby island, where he is picked up by a Portuguese ship that returns him to England and his family. Once Gulliver returns to his family, however, he can only see them as brutish Yahoos. He can barely stand to be in the same room with them. He longs for the Houyhnhnms and spends at least four hours a day talking to his two stallions in their stable.

Lesson Summary

Gulliver’s Travel’s, written by Jonathan Swift, recounts in first-person narrative the vibrant adventures of Lemuel Gulliver, a surgeon who works on ships and time after time encounters himself stranded in new lands, a victim of shipwreck, piracy, and mutiny.

In Lilliput, he’s taken captive by the Lilliputians, miniature people less than six inches tall, where the emperor is surprisingly able to control him until his escapes from Blefuscu. In his following adventure, he’s enslaved by a giant civilization and becomes a figure of entertainment, first by an exploiting farmer and then by the queen and king of Brogdingnab.

Subsequently, he visits the floating island of Laputa, populated by absurd, self-absorbed scientists. On his final adventure to Houyhnhnm Land, he befriends a peaceful civilization of horses who rule over the brutish, humanlike Yahoos. After learning the ways of the Houyhnhnms, Gulliver is unable to adjust to living in society, since he can only view the English like they are Yahoos.

Learning Outcomes

Once you’re through with the lesson, you should be able to:

- Recall who Gulliver is from Gulliver’s Travels

- Explain the importance of Lilliput

- Describe Brobdingnag and the characters Gulliver meets there

- Consider the importance of Laputa and other islands and the inhabitants there

- Recall his adventures to Houyhnhnm

To unlock this lesson you must be a Study.com Member.

Create your account

Jonathan Swift and ‘Gulliver’s Travels’

-

the publication history of the work reveals the extent to which Swift lost control of the production over the Travels: the first edition of the Travels was heavily and illicitly doctored by its printer.

Gulliver’s Travels began life not as the work of a single man, but as a group project. The idea originated with the Scriblerus Club, a group including Swift, John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Arbuthno. The Scriblerus Club was a group of writers and wits devoted to satirising what they perceived as the folly of modern scholarship and science. They invented an author and pedant called Martinus Scriblerus, and wrote an imaginary biography of him, which was finally published in 1741, as The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus.

However, parts of the memoirs were written in the early years of the 1720s, and Pope says that Gulliver’s Travels was formed from a hint in the memoirs. If you actually read the memoirs as they appeared in 1741, you’ll see that chapter 16 describing the travels of Martinus bears a close resemblance to the travels of Gulliver.

If the Travels were initially generated by the Scriblerians interest in mocking pedantry and contemporary science, it was Swift alone who fleshed out the narrative of a Scriblerus character sent off on a series of imaginary journeys. From Swift’s correspondence, we know that the main composition of Gulliver began around the end of 1720, and was finished in the autumn of 1725.

It was not a good time for Swift. While writing A Tale of a Tub, Swift thought he could realise his ambitions for a rise within the church, and the Tory leaders with which he had aligned himself were in the ascendancy. By the time he started work on Gulliver’s Travels things looked bleaker. He had failed to obtain any Church preferment in England, and he had been forced instead to accept a lowly deanery in Ireland. The Tory government had fallen, and his friends and allies impeached by the Whigs. Gulliver’s Travels was in part a virulent attack on the Whig ministry that Swift blamed for these circumstances.

Swift saw the book as politically explosive, and therefore as something that he had to present and position quite carefully in order to avoid prosecution. He secretly sent the manuscript to a publisher, Benjamin Motte. Accompanying the manuscript was a letter asking Motte if he would publish Gulliver’s Travels signed by Gulliver’s imaginary cousin, Richard Sympson. Sympson is the author of the prefatory letter to Gulliver’s Travels.

So already there is a distinct blurring of the boundaries between fact and fiction: in his real life dealings with his publisher, Swift hides behind a fictional figure that later appears within the work itself.

Motte was keen to publish Gulliver’s Travels, and it came out in October 1726, very quickly – in fact, so quickly that Swift was unable to correct proof copies of his work before it appeared in print. When it did appear, he discovered to his horror that not only was it full of misprints, but also that Motte had deliberately altered the text of several passages, cutting out or toning down the sections he thought were too dangerously outspoken. Swift was outraged at this invasion of his authorial rights. While many of the misprints were corrected in the next edition, it was not until 1735, that Motte’s heavy editing of Gulliver’s Travels was removed, then it appeared in Dublin publisher George Faulkner’s multi-volume edition of Swift’s works.

Despite Swift’s fury, Motte’s 1726 edition of Guliver’s Travels was a huge success. The first impression sold out within a week. Within three weeks, ten thousand copies had been sold. Gulliver’s Travels was the talk of the town. Swift’s correspondence from the time is jubilant about its success, but also makes joking references to the fact that he didn’t write it.

So here already we have a rather strange set of relationships established between Swift and the authorship of Gulliver’s Travels. First the book starts out as the product of several minds, a group project. Then it becomes Swift’s own, but one from which he distances himself by pretending that its really by its fictional narrator, Gulliver, and brought to the publisher by Gulliver’s fictional cousin, Sympson. Then the book is published, and rather than getting Swift’s own version of Gulliver’s Travels, the London literati get a version bowdlerised by the publisher. Nonetheless, it is a hit, and Swift revels in the success of ‘his’ book; yet he continues to pretend that it’s not ‘really’ by him. By 1726, the notion of authorship of Gulliver’s Travels is a tricky business.

Fact, Fiction, and Authenticity

Gulliver’s Travels also reveals some strange overlap between fact and fiction. Swift pretends that Gulliver is the author of his travels. And Gulliver himself is obsessed with defending the authenticity of the travels as factual account of his own real life experiences: in a letter from Captain Gulliver, which prefaces the travels, he says:

‘If the Censure of Yahoos could any Way affect me, I should have great reason to complain, that some of them are so bold as to think my Book of Travels a meer Fiction out of Mine own Brain’.

This concern is emphasised in the letter from the publisher to the reader:

‘There is an Air of Truth apparent through the whole; and indeed the Author was so distinguished for his Veracity, that it became a Sort of Proverb among his Neighbours as Redriff, that when any one affirmed a Thing, to say, it was as True as if Mr Gulliver had spoke it’.

This concern that the reader should accept the truth of the fiction continues to be apparent once we get into the travels proper: describing the King of Brobdignag’s Kitchen, Gulliver says:

‘But if I should describe the Kitchen-grate, the prodigious Pots and Kettles, the Joints of Meat turning on the Spits, with many other Particulars; perhaps I should be hardly believed; at least a severe Critick would be apt to think I enlarged a little, as Travellers are often suspected to do…’.

This emphasis on the trueness of the account presented works in part as a parody of emergent traditions in contemporary prose and prose fiction. Those of you who’ve read any of Daniel Defoe’s fictions will know that they are always prefaced with professions of authenticity. Moll Flanders begins:

‘The World is so taken up of late with Novels and Romances that it will be hard for a private History to be taken for Genuine’.

Defoe is attempting to define the veracity of his account in opposition to the fictionality of contemporary romance fiction. But the narrators of romance fiction also stressed that their accounts were genuine fact: the narrator of novelist Eliza Haywood’s prose fiction The British Recluse (1722) begins her story by saying:

‘The following little History (which I can affirm for Truth, having it from the Mouths of those chiefly concerned in it) is a sad Example of what Miseries may Attend a Woman’.

As those of you who have read either Moll Flanders or The British Recluse will know, there isn’t anything all that plausible or realistic about the events that occur in these ‘true’ fictions. The emphasis on authenticity comes hand in hand with a heavy dose of sensationalism.

1803 etching by James Gillray, The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver as King George III and Napoleon respectively [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In a highly competitive book market, this sensationalism became ever and ever more outlandish, as authors struggled to surpass one another in novelty and singularity. In some ways, Gulliver’s Travels satirises the competing commitment to sensationalism and truth claims that characterised contemporary successful prose fiction. It stretches the plausibility of the ‘life and surprising adventures’ genre to its limit, by attempting to pass off as private history an account that is palpably fantastical.

Gulliver’s Travels and Travel Writing

But the emergent novel wasn’t the only genre marked by these defences of authenticity. They are also found in contemporary travel writing. Swift’s use of the name Sympson in his negotiations with his publisher, and his creation of this Sympson as a fictional cousin of Gulliver’s, links him to Captain William Sympson, the equally fictitious author of A New Voyage to the East Indies (1715). A New Voyage asserted in bold terms the autobiographical nature of its account, but was in fact plagiarized from an earlier travel book.

Gulliver’s Travels derived much of its popularity from the contemporary readers’ enthusiastic consumption of travel compilations and the records of journeys and voyages. Swift himself owned a number of accounts by famous travel writers, including the sixteenth century such as travel writers Richard Hakluyt, Samuel Purchas, and William Dampier. There is a sustained imitation of various travel accounts in Gulliver’s Travels: the description of the storm in Book II closely copies the style of a seventeenth narrative called Mariners Magazine by Captain Samuel Sturmy. Swift places the locations of his fictitious voyages in regions visited by one of the most famous travel writers of the period: the pirate, explorer and author William Dampier. Dampier produced an account of his 1699 expedition to Australia, then known as New Holland, which had appeared as a two part account called A Voyage to New Holland published in 1702, and A Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland published in 1709. Lilliput is supposed to be between Van Dieman’s land, which was Tasmania, and the northern coast of Australia. The land of the Houyhnhnms in Book 4 is just south west of Australia.

Gulliver’s Travels also exploits some of the potential for absurdity that was evident in travel accounts. In contemporary travelogues, one way in which authors attempted to emphasize the authenticity of their account was by representing islands in woodcuts as they would appear if they were seen through a telescope. Having no sea shown on them, and cut off at the base, they in fact look as if they’re flying through the air. When Laputa flies over Balnibarbi, Swift literalizes the comic potential of the travel narrative and its illustrative apparatus.

Another important aspect of the travel narrative satirised by Gulliver’s Travels is its function as a form of reflection on contemporary European society. Travelogue’s observations about new nations and experiences could be used to interrogate domestic culture and mores, not always to their advantage. And this aspect of the growing interest in the new world that wasn’t just confined to travel-writing. Contemporaries were fascinated by the possibility that a savage could be noble, revealing by contrast the corruption of a ‘civilised’ voyager (Consider Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko). Gulliver’s progressive disillusionment with his own society, and his preference for the civilised world of the Hounymnyms in the final book, represents this contemporary vogue taken to an extreme: by the end of the fourth book, Gulliver returns to England and can only tolerate the company of horses, and he stuffs his nose with lavender and rue to cut out the smell of mankind.

And as a story, Gulliver’s Travels both capitalises on the commercial vogue for travel writing, and shares some of the excitement of a real travellers tale. We aren’t just distanced readers enjoying the irony of the satire – one of the things that has made the Travels into a children’s classic is that on a basic level of plot and story, we want to know what Gulliver finds, and what happens next.

But the Travels are also a parody. And Gulliver is a splendid liar, masquerading as a purveyor of genuine experiences. Swift draws on the rhetoric of veracity to undercut the truth claims found in contemporary prose and prose fiction. The irony of this satire is that underwriting Gulliver’s Travels is the implicit assumption that this fictional world can in fact tell us the truth about the ‘real’ world of contemporary English society and politics, for the narrative works as a form of allegory. Swift draws on a tradition developed through Thomas More’s Utopia, and the satiric narratives of Rabelais and Cyrano de Bergerac: the tradition of describing fantastic countries that satirise contemporary clerics, politicians, and academics. Like all allegories, these mock-traveller’s tales gesture towards the true state of things by telling a lie, or in the Hounynyms’ phrase, ‘telling the thing that is not’. So Gulliver’s Travels is a fictional tale masquerading as a true story, yet the very fictionality of the account enables Swift author to reveal what it would not be possible to articulate through a genuine account of the nation.

Allegory and Meaning

Allegory provides an interpretative framework within which a ‘true’ set of values or ideas can be communicated, as one narrative gestures toward another which is not directly perceivable or communicable. Allegory does this via a series of equations or equivalences. For example, in A Tale of a Tub, Martin equals Anglicanism, Peter equals Catholicism, and their quarrel equates to the Reformation. The trouble with Gulliver’s Travels is that the allegory does not remain constant: the frame of reference shifts, making it hard to decipher the ultimate reality toward which it points. For example, it is never entirely clear for who or what the figure of Gulliver stands.

At some points Gulliver is a cipher for Swift himself: in the second chapter of the book of Lilliput, Gulliver gives an account of the way in which his excrement has to be carried off in a two wheelbarrows by the Lilliputians. He explains his justification for this detail:

‘I would not have dwelt so long upon a Circumstance, that perhaps at first sight may appear not very Momentous; if I had not thought it necessary to justify my Character in Point of Cleanliness to the World, which I am told, some of my Maligners have been pleased on this and other Occasions, to call in Question’.

This clearly seems to operate as a reference to previous attacks on Swift, whose writings, especially A Tale of a Tub, had been attacked as filthy, lewd, and immodest. Gulliver’s self defence operates as Swift’s own self defence in the face of existing criticisms of his work.

But at different points Gulliver serves as a cipher for other historical figures. For example, at one point he comes to stand in as a figure for Swift’s friend, the disgraced Tory leader Lord Bolingbroke. When Gulliver is arrested by the Lilliputians and forced to stand trial, Gulliver decides to escape rather than testify. Justifying this apparently cowardly decision, he says:

‘Having in my Life perused many State-Tryals, which I ever observed to terminate as the Judges thought fit to direct; I durst not rely on so dangerous a Decision, in so ciritical a Juncture, and against such Powerful Enemies’.

Here Swift, via Gulliver, offers a defence of Bolingbroke’s decision not to stand trial over his part in the Jacobite Atterbury plot of April 1722. We read, in this context, Gulliver’s reasoning as an allegorical figuration of Bolingbroke’s part in recent political history.

But can allegory function in this way? Gulliver’s Travels invites interpretation as an allegory, but the allegorical framework is constantly shifting, making it hard to pin down exactly to what version of ‘reality’ the fiction relates. Who is Gulliver? Is he Swift? Bolingbroke? Locke? Dampier? Ever since the book was first published, readers have tried to ‘fix’ an interpretative system for decoding the topical satirical focus for the Travels. Just two weeks after Gulliver’s Travels came out, newspapers were advertising A Key, Being Obervations and Explanatory Notes, upon the Travels of Lemuel Gulliver (1726), which offered all the necessary identifications for unpicking Swift’s satire. Some of these offered genuinely relevant readings of individual figures (for example, Flimnap as Walpole), but in attempting to offer a systematic explanation of the whole book in terms of topical comment, it revealed just how hard it is to tie much of the Travels down.

While there is substantial pointed topical satire, the targets of Swift’s attack keep changing. One moment he comments on Whig politics in 1720s, and the next he widens out to embrace all human folly. The changes of perspective afforded by our unreliable narrator are almost dizzying, and they make it hard to establish a sense of proportion. This confusion of perspective, and sense of the difficulty in establishing relative values is something that is reflected in Gulliver’s own difficulties in measuring what he sees around him. For example, in ‘Voyage to Brobdignag’, he writes:

‘I was an Hour walking to the end of this Field; which was fenced in with a Hedge of at least one hundred and twenty Foot high, and the Trees so lofty that I could make no Computation of their Altitude’.

When Gulliver arrives back home again, his sense of perspective, of what is the norm, has so altered that he is flummoxed by the size of the members of his family:

‘My Wife ran out to embrace me, but I stooped lower than her Knees, thinking she could otherwise never be able to reach my mouth’.

‘Gulliver Exhibited to the Brobdingnag Farmer’ by Richard Redgrave, 1836 [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Interpretation and Objectivity

One way of looking at these crises of interpretation in Gulliver’s Travels is to consider them alongside the empirical philosophy of John Locke, of which Swift was critical. In his ‘Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ (1690), Locke attempted to investigate the formulation and workings of systems of knowledge. In broad terms, Locke’s essay attacks the idea of imagination as the key to knowledge, in favour of recognising that the mind acquires knowledge through direct experience, empirically:

‘…Men, barely by the use of their natural faculties, may attain to all the knowledge they have, without the help of any innate impressions, and may arrive at certainty without any such original notions or principles’.

At the core of Locke’s philosophy is the argument in which Locke describes the mind at birth as a tabula rasa – a wax tablet as yet unmarked by the impressions that experience will write on it. Experience is something that the mind cannot refuse, and at a basic level, the mind is marked by the initial sensation of the object perceived. From those markings, we use sense and reason to build up a system of knowledge. What we know then, is derived from connections made between perceived experiences – not from any innate wisdom or understanding.

Locke’s theory provoked a debate about what was real. His idea of the materialism of objects external to the body seemed opposed to any sense of inner reality. In Locke’s philosophy of knowledge, reason is elevated above spiritual revelation. For a staunch Anglican like Swift, it seemed to offer a defence or intellectual basis for deism, or atheism. Although Locke’s Essay was initially intended to provide an investigation of the nature of religious belief, many Anglicans thought Locke was creating an epistemology that cut God out of the equation.

We could read Gulliver’s troubles in understanding what he sees as a parody of Locke’s philosophy of human understanding. Gulliver looks to the material world around him to gain a sense of knowledge. There is a great deal of emphasis on what he sees, and a real striving to attain some kind of objectivity, to record his impressions accurately. However, his impressions and his sensory apprehension of those worlds do not help him to gain knowledge. He looks at the trees around him to get a sense of scale, but they do not help. One of the central parts of Lockeian philosophy was that knowledge was not purely derived from sense data, but that man used reason to work out the connections between the ideas received through experience.

However, although Gulliver tries to measure one object against another to establish a correct perspective, he remains unable to establish a secure view of the world. In a broader sense, Gulliver should be able to calibrate moral behaviour by using his external experiences of the people that he meets on his travels as a body of knowledge from which he can derive a sense of an ideal society. In terms of Lockean empiricism, it is significant that Gulliver has no inbuilt, preformed sense of spiritual or inner revelation. All he has is what he sees, and he uses that to define his own moral philosophy.

But the philosophy he arrives at by the end of the book is one which is profoundly misanthropic and patently ridiculous: when he returns home after his voyage to the Hounynyms, he has concluded that he wants to live with horses, and make canoes out of humans. Swift offers us a mind which has indeed been imprinted with what it experiences from the senses, but which is unable to configure these experiences into a useful and meaningful worldview. The ultimate result of all Gulliver’s experiences is a profound disorientation: because he has no innate sense of himself and his own values, he merely tries to internalise the perceptions and value systems of the cultures that he finds himself in, none of which quite match with his own needs.

While evaluating Gulliver’s final philosophy, it is important to bear in mind that book 4 wasn’t the original ending to the book. Swift originally proposed to have the third book last.

This essay is only the beginning of an attempt to situate some of the salient features of Gulliver’s Travels in the context of existing texts and ideas, and to consider how the fantastical world described by Swift’s maverick traveler might relate to wider concerns about the relationship between authenticity and authorship, and authenticity and truth.

Jonathan Swift and ‘Gulliver’s Travels’

-

the publication history of the work reveals the extent to which Swift lost control of the production over the Travels: the first edition of the Travels was heavily and illicitly doctored by its printer.

Gulliver’s Travels began life not as the work of a single man, but as a group project. The idea originated with the Scriblerus Club, a group including Swift, John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Arbuthno. The Scriblerus Club was a group of writers and wits devoted to satirising what they perceived as the folly of modern scholarship and science. They invented an author and pedant called Martinus Scriblerus, and wrote an imaginary biography of him, which was finally published in 1741, as The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus.

However, parts of the memoirs were written in the early years of the 1720s, and Pope says that Gulliver’s Travels was formed from a hint in the memoirs. If you actually read the memoirs as they appeared in 1741, you’ll see that chapter 16 describing the travels of Martinus bears a close resemblance to the travels of Gulliver.

If the Travels were initially generated by the Scriblerians interest in mocking pedantry and contemporary science, it was Swift alone who fleshed out the narrative of a Scriblerus character sent off on a series of imaginary journeys. From Swift’s correspondence, we know that the main composition of Gulliver began around the end of 1720, and was finished in the autumn of 1725.

It was not a good time for Swift. While writing A Tale of a Tub, Swift thought he could realise his ambitions for a rise within the church, and the Tory leaders with which he had aligned himself were in the ascendancy. By the time he started work on Gulliver’s Travels things looked bleaker. He had failed to obtain any Church preferment in England, and he had been forced instead to accept a lowly deanery in Ireland. The Tory government had fallen, and his friends and allies impeached by the Whigs. Gulliver’s Travels was in part a virulent attack on the Whig ministry that Swift blamed for these circumstances.

Swift saw the book as politically explosive, and therefore as something that he had to present and position quite carefully in order to avoid prosecution. He secretly sent the manuscript to a publisher, Benjamin Motte. Accompanying the manuscript was a letter asking Motte if he would publish Gulliver’s Travels signed by Gulliver’s imaginary cousin, Richard Sympson. Sympson is the author of the prefatory letter to Gulliver’s Travels.

So already there is a distinct blurring of the boundaries between fact and fiction: in his real life dealings with his publisher, Swift hides behind a fictional figure that later appears within the work itself.

Motte was keen to publish Gulliver’s Travels, and it came out in October 1726, very quickly – in fact, so quickly that Swift was unable to correct proof copies of his work before it appeared in print. When it did appear, he discovered to his horror that not only was it full of misprints, but also that Motte had deliberately altered the text of several passages, cutting out or toning down the sections he thought were too dangerously outspoken. Swift was outraged at this invasion of his authorial rights. While many of the misprints were corrected in the next edition, it was not until 1735, that Motte’s heavy editing of Gulliver’s Travels was removed, then it appeared in Dublin publisher George Faulkner’s multi-volume edition of Swift’s works.

Despite Swift’s fury, Motte’s 1726 edition of Guliver’s Travels was a huge success. The first impression sold out within a week. Within three weeks, ten thousand copies had been sold. Gulliver’s Travels was the talk of the town. Swift’s correspondence from the time is jubilant about its success, but also makes joking references to the fact that he didn’t write it.

So here already we have a rather strange set of relationships established between Swift and the authorship of Gulliver’s Travels. First the book starts out as the product of several minds, a group project. Then it becomes Swift’s own, but one from which he distances himself by pretending that its really by its fictional narrator, Gulliver, and brought to the publisher by Gulliver’s fictional cousin, Sympson. Then the book is published, and rather than getting Swift’s own version of Gulliver’s Travels, the London literati get a version bowdlerised by the publisher. Nonetheless, it is a hit, and Swift revels in the success of ‘his’ book; yet he continues to pretend that it’s not ‘really’ by him. By 1726, the notion of authorship of Gulliver’s Travels is a tricky business.

Fact, Fiction, and Authenticity

Gulliver’s Travels also reveals some strange overlap between fact and fiction. Swift pretends that Gulliver is the author of his travels. And Gulliver himself is obsessed with defending the authenticity of the travels as factual account of his own real life experiences: in a letter from Captain Gulliver, which prefaces the travels, he says:

‘If the Censure of Yahoos could any Way affect me, I should have great reason to complain, that some of them are so bold as to think my Book of Travels a meer Fiction out of Mine own Brain’.

This concern is emphasised in the letter from the publisher to the reader:

‘There is an Air of Truth apparent through the whole; and indeed the Author was so distinguished for his Veracity, that it became a Sort of Proverb among his Neighbours as Redriff, that when any one affirmed a Thing, to say, it was as True as if Mr Gulliver had spoke it’.

This concern that the reader should accept the truth of the fiction continues to be apparent once we get into the travels proper: describing the King of Brobdignag’s Kitchen, Gulliver says:

‘But if I should describe the Kitchen-grate, the prodigious Pots and Kettles, the Joints of Meat turning on the Spits, with many other Particulars; perhaps I should be hardly believed; at least a severe Critick would be apt to think I enlarged a little, as Travellers are often suspected to do…’.

This emphasis on the trueness of the account presented works in part as a parody of emergent traditions in contemporary prose and prose fiction. Those of you who’ve read any of Daniel Defoe’s fictions will know that they are always prefaced with professions of authenticity. Moll Flanders begins:

‘The World is so taken up of late with Novels and Romances that it will be hard for a private History to be taken for Genuine’.

Defoe is attempting to define the veracity of his account in opposition to the fictionality of contemporary romance fiction. But the narrators of romance fiction also stressed that their accounts were genuine fact: the narrator of novelist Eliza Haywood’s prose fiction The British Recluse (1722) begins her story by saying:

‘The following little History (which I can affirm for Truth, having it from the Mouths of those chiefly concerned in it) is a sad Example of what Miseries may Attend a Woman’.

As those of you who have read either Moll Flanders or The British Recluse will know, there isn’t anything all that plausible or realistic about the events that occur in these ‘true’ fictions. The emphasis on authenticity comes hand in hand with a heavy dose of sensationalism.

1803 etching by James Gillray, The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver as King George III and Napoleon respectively [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In a highly competitive book market, this sensationalism became ever and ever more outlandish, as authors struggled to surpass one another in novelty and singularity. In some ways, Gulliver’s Travels satirises the competing commitment to sensationalism and truth claims that characterised contemporary successful prose fiction. It stretches the plausibility of the ‘life and surprising adventures’ genre to its limit, by attempting to pass off as private history an account that is palpably fantastical.

Gulliver’s Travels and Travel Writing

But the emergent novel wasn’t the only genre marked by these defences of authenticity. They are also found in contemporary travel writing. Swift’s use of the name Sympson in his negotiations with his publisher, and his creation of this Sympson as a fictional cousin of Gulliver’s, links him to Captain William Sympson, the equally fictitious author of A New Voyage to the East Indies (1715). A New Voyage asserted in bold terms the autobiographical nature of its account, but was in fact plagiarized from an earlier travel book.

Gulliver’s Travels derived much of its popularity from the contemporary readers’ enthusiastic consumption of travel compilations and the records of journeys and voyages. Swift himself owned a number of accounts by famous travel writers, including the sixteenth century such as travel writers Richard Hakluyt, Samuel Purchas, and William Dampier. There is a sustained imitation of various travel accounts in Gulliver’s Travels: the description of the storm in Book II closely copies the style of a seventeenth narrative called Mariners Magazine by Captain Samuel Sturmy. Swift places the locations of his fictitious voyages in regions visited by one of the most famous travel writers of the period: the pirate, explorer and author William Dampier. Dampier produced an account of his 1699 expedition to Australia, then known as New Holland, which had appeared as a two part account called A Voyage to New Holland published in 1702, and A Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland published in 1709. Lilliput is supposed to be between Van Dieman’s land, which was Tasmania, and the northern coast of Australia. The land of the Houyhnhnms in Book 4 is just south west of Australia.

Gulliver’s Travels also exploits some of the potential for absurdity that was evident in travel accounts. In contemporary travelogues, one way in which authors attempted to emphasize the authenticity of their account was by representing islands in woodcuts as they would appear if they were seen through a telescope. Having no sea shown on them, and cut off at the base, they in fact look as if they’re flying through the air. When Laputa flies over Balnibarbi, Swift literalizes the comic potential of the travel narrative and its illustrative apparatus.

Another important aspect of the travel narrative satirised by Gulliver’s Travels is its function as a form of reflection on contemporary European society. Travelogue’s observations about new nations and experiences could be used to interrogate domestic culture and mores, not always to their advantage. And this aspect of the growing interest in the new world that wasn’t just confined to travel-writing. Contemporaries were fascinated by the possibility that a savage could be noble, revealing by contrast the corruption of a ‘civilised’ voyager (Consider Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko). Gulliver’s progressive disillusionment with his own society, and his preference for the civilised world of the Hounymnyms in the final book, represents this contemporary vogue taken to an extreme: by the end of the fourth book, Gulliver returns to England and can only tolerate the company of horses, and he stuffs his nose with lavender and rue to cut out the smell of mankind.

And as a story, Gulliver’s Travels both capitalises on the commercial vogue for travel writing, and shares some of the excitement of a real travellers tale. We aren’t just distanced readers enjoying the irony of the satire – one of the things that has made the Travels into a children’s classic is that on a basic level of plot and story, we want to know what Gulliver finds, and what happens next.

But the Travels are also a parody. And Gulliver is a splendid liar, masquerading as a purveyor of genuine experiences. Swift draws on the rhetoric of veracity to undercut the truth claims found in contemporary prose and prose fiction. The irony of this satire is that underwriting Gulliver’s Travels is the implicit assumption that this fictional world can in fact tell us the truth about the ‘real’ world of contemporary English society and politics, for the narrative works as a form of allegory. Swift draws on a tradition developed through Thomas More’s Utopia, and the satiric narratives of Rabelais and Cyrano de Bergerac: the tradition of describing fantastic countries that satirise contemporary clerics, politicians, and academics. Like all allegories, these mock-traveller’s tales gesture towards the true state of things by telling a lie, or in the Hounynyms’ phrase, ‘telling the thing that is not’. So Gulliver’s Travels is a fictional tale masquerading as a true story, yet the very fictionality of the account enables Swift author to reveal what it would not be possible to articulate through a genuine account of the nation.

Allegory and Meaning

Allegory provides an interpretative framework within which a ‘true’ set of values or ideas can be communicated, as one narrative gestures toward another which is not directly perceivable or communicable. Allegory does this via a series of equations or equivalences. For example, in A Tale of a Tub, Martin equals Anglicanism, Peter equals Catholicism, and their quarrel equates to the Reformation. The trouble with Gulliver’s Travels is that the allegory does not remain constant: the frame of reference shifts, making it hard to decipher the ultimate reality toward which it points. For example, it is never entirely clear for who or what the figure of Gulliver stands.

At some points Gulliver is a cipher for Swift himself: in the second chapter of the book of Lilliput, Gulliver gives an account of the way in which his excrement has to be carried off in a two wheelbarrows by the Lilliputians. He explains his justification for this detail:

‘I would not have dwelt so long upon a Circumstance, that perhaps at first sight may appear not very Momentous; if I had not thought it necessary to justify my Character in Point of Cleanliness to the World, which I am told, some of my Maligners have been pleased on this and other Occasions, to call in Question’.

This clearly seems to operate as a reference to previous attacks on Swift, whose writings, especially A Tale of a Tub, had been attacked as filthy, lewd, and immodest. Gulliver’s self defence operates as Swift’s own self defence in the face of existing criticisms of his work.

But at different points Gulliver serves as a cipher for other historical figures. For example, at one point he comes to stand in as a figure for Swift’s friend, the disgraced Tory leader Lord Bolingbroke. When Gulliver is arrested by the Lilliputians and forced to stand trial, Gulliver decides to escape rather than testify. Justifying this apparently cowardly decision, he says:

‘Having in my Life perused many State-Tryals, which I ever observed to terminate as the Judges thought fit to direct; I durst not rely on so dangerous a Decision, in so ciritical a Juncture, and against such Powerful Enemies’.

Here Swift, via Gulliver, offers a defence of Bolingbroke’s decision not to stand trial over his part in the Jacobite Atterbury plot of April 1722. We read, in this context, Gulliver’s reasoning as an allegorical figuration of Bolingbroke’s part in recent political history.

But can allegory function in this way? Gulliver’s Travels invites interpretation as an allegory, but the allegorical framework is constantly shifting, making it hard to pin down exactly to what version of ‘reality’ the fiction relates. Who is Gulliver? Is he Swift? Bolingbroke? Locke? Dampier? Ever since the book was first published, readers have tried to ‘fix’ an interpretative system for decoding the topical satirical focus for the Travels. Just two weeks after Gulliver’s Travels came out, newspapers were advertising A Key, Being Obervations and Explanatory Notes, upon the Travels of Lemuel Gulliver (1726), which offered all the necessary identifications for unpicking Swift’s satire. Some of these offered genuinely relevant readings of individual figures (for example, Flimnap as Walpole), but in attempting to offer a systematic explanation of the whole book in terms of topical comment, it revealed just how hard it is to tie much of the Travels down.

While there is substantial pointed topical satire, the targets of Swift’s attack keep changing. One moment he comments on Whig politics in 1720s, and the next he widens out to embrace all human folly. The changes of perspective afforded by our unreliable narrator are almost dizzying, and they make it hard to establish a sense of proportion. This confusion of perspective, and sense of the difficulty in establishing relative values is something that is reflected in Gulliver’s own difficulties in measuring what he sees around him. For example, in ‘Voyage to Brobdignag’, he writes:

‘I was an Hour walking to the end of this Field; which was fenced in with a Hedge of at least one hundred and twenty Foot high, and the Trees so lofty that I could make no Computation of their Altitude’.

When Gulliver arrives back home again, his sense of perspective, of what is the norm, has so altered that he is flummoxed by the size of the members of his family:

‘My Wife ran out to embrace me, but I stooped lower than her Knees, thinking she could otherwise never be able to reach my mouth’.

‘Gulliver Exhibited to the Brobdingnag Farmer’ by Richard Redgrave, 1836 [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Interpretation and Objectivity

One way of looking at these crises of interpretation in Gulliver’s Travels is to consider them alongside the empirical philosophy of John Locke, of which Swift was critical. In his ‘Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ (1690), Locke attempted to investigate the formulation and workings of systems of knowledge. In broad terms, Locke’s essay attacks the idea of imagination as the key to knowledge, in favour of recognising that the mind acquires knowledge through direct experience, empirically:

‘…Men, barely by the use of their natural faculties, may attain to all the knowledge they have, without the help of any innate impressions, and may arrive at certainty without any such original notions or principles’.

At the core of Locke’s philosophy is the argument in which Locke describes the mind at birth as a tabula rasa – a wax tablet as yet unmarked by the impressions that experience will write on it. Experience is something that the mind cannot refuse, and at a basic level, the mind is marked by the initial sensation of the object perceived. From those markings, we use sense and reason to build up a system of knowledge. What we know then, is derived from connections made between perceived experiences – not from any innate wisdom or understanding.

Locke’s theory provoked a debate about what was real. His idea of the materialism of objects external to the body seemed opposed to any sense of inner reality. In Locke’s philosophy of knowledge, reason is elevated above spiritual revelation. For a staunch Anglican like Swift, it seemed to offer a defence or intellectual basis for deism, or atheism. Although Locke’s Essay was initially intended to provide an investigation of the nature of religious belief, many Anglicans thought Locke was creating an epistemology that cut God out of the equation.

We could read Gulliver’s troubles in understanding what he sees as a parody of Locke’s philosophy of human understanding. Gulliver looks to the material world around him to gain a sense of knowledge. There is a great deal of emphasis on what he sees, and a real striving to attain some kind of objectivity, to record his impressions accurately. However, his impressions and his sensory apprehension of those worlds do not help him to gain knowledge. He looks at the trees around him to get a sense of scale, but they do not help. One of the central parts of Lockeian philosophy was that knowledge was not purely derived from sense data, but that man used reason to work out the connections between the ideas received through experience.

However, although Gulliver tries to measure one object against another to establish a correct perspective, he remains unable to establish a secure view of the world. In a broader sense, Gulliver should be able to calibrate moral behaviour by using his external experiences of the people that he meets on his travels as a body of knowledge from which he can derive a sense of an ideal society. In terms of Lockean empiricism, it is significant that Gulliver has no inbuilt, preformed sense of spiritual or inner revelation. All he has is what he sees, and he uses that to define his own moral philosophy.

But the philosophy he arrives at by the end of the book is one which is profoundly misanthropic and patently ridiculous: when he returns home after his voyage to the Hounynyms, he has concluded that he wants to live with horses, and make canoes out of humans. Swift offers us a mind which has indeed been imprinted with what it experiences from the senses, but which is unable to configure these experiences into a useful and meaningful worldview. The ultimate result of all Gulliver’s experiences is a profound disorientation: because he has no innate sense of himself and his own values, he merely tries to internalise the perceptions and value systems of the cultures that he finds himself in, none of which quite match with his own needs.

While evaluating Gulliver’s final philosophy, it is important to bear in mind that book 4 wasn’t the original ending to the book. Swift originally proposed to have the third book last.

This essay is only the beginning of an attempt to situate some of the salient features of Gulliver’s Travels in the context of existing texts and ideas, and to consider how the fantastical world described by Swift’s maverick traveler might relate to wider concerns about the relationship between authenticity and authorship, and authenticity and truth.

Source https://study.com/learn/lesson/gullivers-travels-by-jonathan-swift-summary-characters-analysis.html

Source https://writersinspire.org/content/jonathan-swift-gullivers-travels

Source https://writersinspire.org/content/jonathan-swift-gullivers-travels