The Concept of Travel in Art Through the Ages

This post is part of the ArtSmart Roundtable, a group of travel and art bloggers bringing you themed posts every month. This month’s post theme is “concept”, so I’ve decided to tap into what Wanderarti does best – talk about travel in art. Scroll to the bottom to see more of this month’s awesome posts!

For as long as the timeline of art spans back there are paintings of places; depictions of destinations rendered carefully and thoughtfully by both famous artists and lesser-known explorers.

Landscape painting is perhaps the most prominent and most recognisable form of travel art.

Thick brushstrokes bring to life far-flung places; bold colours pinpoint fascinating scenes; realistic portraits showcase lesser-known destinations that would otherwise go undocumented.

Travel in Art in the 17th Century

Back in the 17th century, European landscape art was on the rise. It was a dominant genre during this time thanks to the unprecedented growth of global travel and tourism.

But there’s a conundrum here: it’s the chicken vs the egg debate when it comes to travel and art. Did the explorer set out to paint or did the artist set out to explore?

Through the 17th century and the following 200 years, travel was no longer a means from moving one group of people to another place (a form of travel that, for the most part, has been imbued into human life since the very beginning). It wasn’t just kings, queens, and traders who traversed landscapes far and wide.

Geographical exploration was on the rise, and colonial expansion was well and truly underway. This meant big things for the art world.

Without photographs or social media, explorers used the mediums of sketching and painting to document places. They combined skill and an expert eye for detail to produce scenes they had witnessed on their travels – to bring back and show family, friends, and those who were less able to travel.

William Hodges via Wiki Commons

Trips during this time were lengthy and, usually, with purpose. It was impossible to pop to Cairo for a weekend, or explore the South American jungle in a couple of weeks.

Journeys lasted for months on end, with explorers turning to art to create stories about the places they visited – to immortalise languages, scenery, and customs that were otherwise unfamiliar to them.

But, despite efforts to portray countries, cities, and destinations in an objective light, this is art we’re talking about. Even in the most skilfully executed landscape piece, there will always been a hint of political, social, and cultural significance depending on the person creating the painting.

Subjective observations creep into well-rendered pieces, offering viewers not just a glimpse into places from the past, but also an insight into the mind-set of explorers.

Even though just one explorer might have been producing the artwork, it was more of a collective experience. There was a vested interest in creating realistic depictions of other places because it hadn’t been done before.

Take the imagery created by 19th century explorers who ventured around the Pacific. Work produced by men aboard Captain James Cook’s ships in the 18th century immortalised places that had never been seen by the western world before. There was a vested interest from the west to learn more about these places – for trading and other political reasons.

Travel in Art in the Mid-19th Century

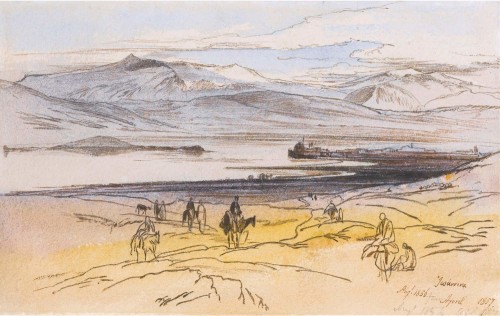

Jump forward to the mid-19th century. After teaching Queen Victoria how to wield a paintbrush, Edward Lear set out to explore distant lands, painting their oddities as he went.

Lear was different to the men who had been aboard Cook’s ship and those that came before him because he was, first and foremost, an artist. He wasn’t a trader, a soldier, or a voyager. His livelihood was made from painting.

Greece by Edward Lear

At a time when barely anyone had the opportunity to travel (remember the long distances and difficulties in getting from one place to the next), Lear opened a gateway to the world for those less able than him.

From Italy, Albania, Greece, Egypt, and India, he immersed himself in the local culture and drew pictures that he felt reflected the place in its rawest form. There were seemingly no political backdrops to his work and underhand motivations. He simply wanted to bring the world to the world.

This was the start of something beautiful in the art world. Landscape paintings and depictions of “exotic” destinations were no longer driven by an ulterior motive. They were simply representations of the beautiful and the “other”.

Travel in Art in the 20th Century

Skip forward a century and this is even more evident to see. World-famous artists like Matisse, Derain and Picasso were creating piece after piece that showcased destinations around Europe.

These weren’t realistic renditions, though. In fact, they were a far cry from the beige swathes of sketches created by early voyagers and even Lear himself.

They were bold and bright, injected with a heavy dose of the artists’ recognisable style. Matisse’s paintings from Couillere were, at first glance, just splodges of paint in a wheel of surreal colours. Derain’s depictions of London were psychedelic, using the Pointillism technique to create abstract versions of scenes.

Gift and bequest of Louise Reinhardt Smith © 2015 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

At this point, art was no longer a vessel to share objective scenes and stories from around the world. It was a portal into the minds and souls of creative greats. There were already hundreds, if not thousands, of depictions of places around the world – what good would even more do?

André Derain, 1906, Charing Cross Bridge, London, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Instead, artists used the backdrop of places to express their feelings and thoughts about them. Matisse’s pieces from Couillere may not have shown visitors exactly what to expect in terms of scenery, but the brash use of colour and thick brush strokes might just give an insight into how he felt about the French town.

This notion of art being a personal endeavour rather than collective continues into the present day.

Sure, artistic versions of places hint at architectural styles, local life, and customs, but more than that they delve into personal journeys, highlighting individual thoughts and feelings rather than a collective vision of the world.

Since documents began, art has served as an important inspiration for imagination. It’s served as a portal through which people can remember places, cultures, and journeys, as well as depict the motivations behind travel – from the Grand Tour, through the years of globalisation, right up until the present day.

Today travel art is so much more than simply a depiction of a place. They say a painting speaks a thousand words – especially in an age where photographs are a dime a dozen. They not only act as a portal through which we can see another view of a place, but they also act as a personal reminder that’s much more intimate than a photo could ever be.

History of travelling

I was always curious about the reason people started to travel. Was it for pure leisure? To relax? Or to learn about new cultures, and find themselves along the way?

I wanted to chaise the reason all the way to its source – to the first travellers. And hopped to find out what was the initial motivation for people to travel.

According to linguists, the word ‘travel’ was first used in the 14th century. However, people started to travel much earlier.

While looking at the history of travelling and the reasons people started to travel, I wanted to distinguish the difference between travellers and explorers. Most of the time, when thinking about travel in history, people like Marco Polo or Christopher Columbus are coming to mind. However, they weren’t really travellers in a modern sense. They were explorers and researchers. So, to really learn about how people started to travel, I wanted to focus on ordinary people. Travellers like you and me, if you wish.

Romans and their roads

First people who started to travel for enjoyment only were, I’m sure you won’t be surprised, old Romans. Wealthy Romans would often go to their summer villas. And it was purely for leisure. They could, of course, start doing that because they invented something quite crucial for travelling – roads. Well developed network of roads was the reason they could travel safely and quickly.

However, there is another reason that motivated people in Antiquity to travel. And I was quite amazed when I learned about it.

It was a desire to learn. They believed travelling is an excellent way to learn about other cultures, by observing their art, architecture and listening to their languages.

Sounds familiar? It seems like Romans were the first culture tourists.

Travelling during the Middle Ages

It may come by surprise, but people started to wander more during the Middle Ages. And most of those journeys were pilgrimages.

Religion was the centre of life back in the Middle Ages. And the only things that connected this world with the saints people were worshipping, were the relics of saints. Pilgrims would often travel to another part of the country, or even Europe to visit some of the sacred places.

The most popular destinations for all those pilgrims was Santiago de Compostela, located in northwest Spain. People would travel for thousands of kilometres to reach it. To make a journey a bit easier for them, and to earn money from the newly developed tourism, many guest houses opened along the way. Pilgrims would often visit different towns and churches on their way, and while earning a ticket to heaven, do some sightseeing, as well.

Wealthy people were travelling in the caravans or by using the waterways. What’s changing in the Middle Ages was that travel wasn’t reserved only for the rich anymore. Lower classes are starting to travel, as well. They were travelling on foot, sleeping next to the roads or at some affordable accommodations. And were motivated by religious purposes.

⤷ TIP: You can still find many of those old pilgrim’s routes in Europe. When in old parts of the cities (especially in Belgium and the Netherlands), look for the scallop shells on the roads. They will lead you to the local Saint-Jacob’s churches. Places dedicated to that saint were always linked to pilgrims and served as stops on their long journeys. In some cities, like in Antwerp, you can follow the scallop shell trails even today.

Below you can see one of the scallop shells on a street and Saint-Jacques Church in Tournai, Belgium.

Grand Tours of the 17th century

More impoverished people continued to travel for religious reasons during the following centuries. However, a new way of travelling appeared among wealthy people in Europe.

Grand tours are becoming quite fashionable among the young aristocrats at the beginning of the 17th century. As a part of their education (hmmm… culture tourists, again?) they would go on a long journey during which they were visiting famous European cities. Such as London, Paris, Rome or Venice, and were learning about their art, history and architecture.

Later on, those grand tours became more structured, and they were following precisely the same route. Often, young students would be accompanied by an educational tutor. And just to make the things easier for them, they were allowed to have their servants with them, too.

One of those young aristocrats was a young emperor, Peter the Great of Russia. He travelled around western Europe and has spent a significant amount of his time in the Netherlands. The architecture of Amsterdam and other Dutch cities definitely inspired a layout of the new city he has built – Saint Petersburg. So, travelling definitely remains an essential part of education since Roman times.

The railway system and beginning of modern travel in the 19th century

Before the railway system was invented, people mostly travelled on foot (budget travel) or by water (the first-class travel at that time). However, when in the 1840s, an extensive network of railways was built, people started to travel for fun.

Mid-19th century definitely marks a real beginning of modern tourism. It’s the time when the middle class started to grow. And they have found a way to travel easily around Europe.

It’s coming by no surprise that the first travel agency, founded by Thomas Cook in England, was established at that time, too. He was using recently developed trains together with a network of hotels to organise his first group trips.

History of travelling in the 20th century

Since then, things started to move quickly. With the development of transportation, travelling became much more accessible. Dutch ships would need around a year to travel from Amsterdam to Indonesia. Today, for the same trip, we need less than a day on a plane.

After the Second World War, with the rise of air travel, people started to travel more and more. And with the internet and all the cool apps we have on our smartphones, it’s easier than ever to move and navigate your way in a new country. Mass tourism developed in the 1960s. But, with the new millennium, we started to face the over-tourism.

We can be anywhere in the world in less than two days. And although it’s a great privilege of our time, it also bears some responsibilities. However, maybe the key is to learn from history again and do what old Romans did so well. Travel to learn, explore local history and art, and be true culture tourists.

History of Flight: Breakthroughs, Disasters and More

From hot-air balloons floating over Paris to a dirigible crashing over New Jersey, here are some of the biggest moments of aviation history.

Paul Popper/Popperfoto via Getty Images

From hot-air balloons floating over Paris to a dirigible crashing over New Jersey, here are some of the biggest moments of aviation history.

For thousands of years, humans have dreamed of taking to the skies. The quest has led from kite flying in ancient China to hydrogen-powered hot-air balloons in 18th-century France to contemporary aircraft so sophisticated they can’t be detected by radar or the human eye.

Below is a timeline of humans’ obsession with flight, from da Vinci to drones. Fasten your seatbelt and prepare for liftoff.

1505-06: Da Vinci dreams of flight, publishes his findings

Self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci

DEA / A. DAGLI ORTI/Getty Images

Few figures in history had more detailed ideas, theories and imaginings on aviation as the Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci. His book Codex on the Flight of Birds contained thousands of notes and hundreds of sketches on the nature of flight and aerodynamic principles that would lay much of the early groundwork for—and greatly influence—the development of aviation and manmade aircraft.

November 21, 1783: First manned hot-air balloon flight

Two months after French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier engineered a successful test flight with a duck, a sheep and a rooster as passengers, two humans ascended in a Montgolfier-designed balloon over Paris. Powered by a hand-fed fire, the paper-and-silk aircraft rose 500 vertical feet and traveled some 5.5 miles over about half an hour. But in an 18th-century version of the space race, rival balloon engineers Jacques Alexander Charles and Nicholas Louis Robert upped the ante just 10 days later. Their balloon, powered by hydrogen gas, traveled 25 miles and stayed aloft more than two hours.

1809-1810: Sir George Cayley introduces aerodynamics

At the dawn of the 19th century, English philosopher George Cayley published “On Aerial Navigation,” a radical series of papers credited with introducing the world to the study of aerodynamics. By that time, the man who came to be known as “the father of aviation” had already been the first to identify the four forces of flight (weight, lift, drag, thrust), developed the first concept of a fixed-wing flying machine and designed the first glider reported to have carried a human aloft.

WATCH: Full episodes of ‘The Machines That Built America’ online now and tune in for all-new episodes Sundays at 9/8c.

September 24, 1852: Giffard’s dirigible proves powered air travel is possible

Half a century before the Wright brothers took to the skies, French engineer Henri Giffard manned the first-ever powered and controllable airborne flight. Giffard, who invented the steam injector, traveled almost 17 miles from Paris to Élancourt in his “Giffard Dirigible,” a 143-foot-long, cigar-shaped airship loosely steered by a three-bladed propeller that was powered by a 250-pound, 3-horsepower engine, itself lit by a 100-pound boiler. The flight proved that a steam-powered airship could be steered and controlled.

1876: The internal combustion engine changes everything

Building on advances by French engineers, German engineer Nikolaus Otto devised a lighter, more efficient, gas-powered combustion engine, providing an alternative to the previously universal steam-powered engine. In addition to revolutionizing automobile travel, the innovation ushered in a new era of longer, more controlled aviation.

December 17, 1903: The Wright brothers become airborne—briefly

Flying from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first controlled, sustained flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft. Each brother flew their wooden, gasoline-powered propeller biplane, the “Wright Flyer,” twice (four flights total), with the shortest lasting 12 seconds and the longest sustaining flight for about 59 seconds. Considered a historic event today, the feat was largely ignored by newspapers of the time, who believed the flights were too short to be important.

1907: The first helicopter lifts off

A vintage French postcard featuring the helicopter of Paul Cornu of Lisieux, France, who piloted the first manned flight of a rotary wing aircraft in November 1907.

Paul Popper/Popperfoto via Getty Images

French engineer and bicycle maker Paul Cornu became the first man to ride a rotary-wing, vertical-lift aircraft, a precursor to today’s helicopter, when he was lifted about 1.5 meters off the ground for 20 seconds near Lisieux, France. Versions of the helicopter had been toyed with in the past—Italian engineer Enrico Forlanini debuted the first rotorcraft three decades prior in 1877. And it would be improved upon in the future, with American designer Igor Sikorsky introducing a more standardized version in Stratford, Connecticut in 1939. But it was Cornu’s short flight that would land him in the history books as the definitive first.

1911-12: Harriet Quimby achieves two firsts for women pilots

Journalist Harriet Quimby became the first American woman ever awarded a pilot’s license in 1911, after just four months of flight lessons. Capitalizing on her charisma and showmanship (she became as famous for her violet satin flying suit as for her attention to safety checks), Quimby achieved another first the following year when she became the first woman to fly solo across the English channel. The feat was overshadowed, however, by the sinking of the Titanic two days earlier.

October 1911: The aircraft becomes militarized

Italy became the first country to significantly incorporate aircraft into military operations when, during the Turkish-Italian war, it employed both monoplanes and airships for bombing, reconnaissance and transportation. Within a few years, aircraft would play a decisive role in the World War I.

January 1, 1914: First commercial passenger flight

On New Year’s Day, pilot Tony Jannus transported a single passenger, Mayor Abe Pheil of St. Petersburg, Florida across Tampa Bay via his flying airboat, the “St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line.” The 23-mile flight (mostly along the Tampa Bay shore) cost $5.00 and would lay the foundation for the commercial airline industry.

1914-1918: World war accelerates the militarization of aircraft

World War I became the first major conflict to use aircraft on a large-scale, expanding their use in active combat. Nations appointed high-ranking generals to oversee air strategy, and a new breed of war hero emerged: the fighter pilot or “flying ace.”

According to The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft, France was the war’s leading aircraft manufacturer, producing nearly 68,000 planes between 1914 and 1918. Of those, nearly 53,000 were shot down, crashed or damaged.

June 1919: First nonstop transatlantic flight

The first nonstop transatlantic flight ended with a nosedive into a bog in western Ireland. The pilots walked away unscathed.

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Recommended for you

Louisiana

Paris Commune of 1871

Why the War of 1812 Was a Turning Point for Native Americans

Flying a modified ‘Vickers Vimy’ bomber from the Great War, British aviators and war veterans John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first-ever nonstop transatlantic flight. Their perilous 16-hour journey, undertaken eight years before Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic alone, started in St. John’s, Newfoundland, where they barely cleared the trees at the end of the runway. After a calamity-filled flight, they crash-landed in a peat bog in County Galway, Ireland; remarkably, neither man was injured.

1921: Bessie Coleman becomes the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license

Pioneering aviatrix Bessie Coleman

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The fact that Jim Crow-era U.S. flight schools wouldn’t accept a Black woman didn’t stop Bessie Coleman. Instead, the Texas-born sharecropper’s daughter, one of 13 siblings, learned French so she could apply to the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. There, in 1921, she became the first African American woman to earn a pilot’s license. After performing the first public flight by a Black woman in 1922—including her soon-to-be trademark loop-the-loop and figure-8 aerial maneuvers—she became renowned for her thrilling daredevil air shows and for using her growing fame to encourage Black Americans to pursue flying. Coleman died tragically in 1926, as a passenger in a routine test flight. Thousands reportedly attended her funeral in Chicago.

1927: Lucky Lindy makes first solo transatlantic flight

Charles Lindbergh with his historic plane ‘Spirit of St. Louis’

Nearly a decade after Alcock and Brown made their transatlantic flight together, 25-year-old Charles Lindbergh of Detroit was thrust into worldwide fame when he completed the first solo crossing, just a few days after a pair of celebrated French aviators perished in their own attempt. Flying the “Spirit of St. Louis” aircraft from New York to Paris, “Lucky Lindy” made the first transatlantic voyage between two major hubs—and the longest transatlantic flight by more than 2,000 miles. The feat instantly made Lindbergh one of the great folk heroes of his time, earned him the Medal of Honor and helped usher in a new era of interest in the possibilities of aviation.

1932: Amelia Earhart repeats Lindbergh’s feat

Aviatrix Amelia Earhart

Five years after Lindbergh completed his flight, “Lady Lindy” Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, setting off from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland on May 20, 1932 and landing some 14 hours later in Culmore, Northern Ireland. In her career as an aviator, Earhart would become a worldwide celebrity, setting several women’s speed, domestic distance and transcontinental aviation records. Her most memorable feat, however, would prove to be her last. In 1937, while attempting to circumnavigate the globe, Earhart disappeared over the central Pacific ocean and was never seen or heard from again.

1937: The Hindenburg crashes…along with the ‘Age of Airships’

The Hindenburg bursts into blames above Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937.

Between WWI and WWII, aviation pioneers and major aircraft companies like Germany’s Luftshiffbau Zeppelin tried hard to popularize bulbous, lighter-than-air airships—essentially giant flying gas bags—as a mode of commercial transportation. The promise of the steam-powered, hydrogen-filled airships quickly evaporated, however, after the infamous 1937 Hindenburg disaster. That’s when the gas inside the Zeppelin company’s flagship Hindenburg vessel exploded during a landing attempt, killing 35 passengers and crew members and badly burning the majority of the 62 remaining survivors.

October 14, 1947: Chuck Yeager breaks the sound barrier

An ace combat fighter during WWII, Chuck Yeager earned the title “Fastest Man Alive” when he hit 700 m.p.h. while testing the experimental X-1 supersonic rocket jet for the military over the Mojave Desert in 1947. Being the first person to travel faster than the speed of sound has been hailed as one of the most epic feats in the history of aviation—not bad for someone who got sick to his stomach after his first-ever flight.

1949: The world’s first commercial jetliner takes off

Early passenger air travel was noisy, cold, uncomfortable and bumpy, as planes flew at low altitudes that brought them through, not above, the weather. But when the British-manufactured de Havilland Comet took its first flight in 1949—boasting four turbine engines, a pressurized cabin, large windows and a relatively comfortable seating area—it marked a pivotal step in modern commercial air travel. An early, flawed design however, caused the de Havilland to be grounded after a series of mid-flight disasters—but not before giving the world a glimpse of what was possible.

1954-1957: Boeing glamorizes flying

With the debut of the sleek 707 aircraft, touted for its comfort, speed and safety, Seattle-based Boeing ushered in the age of modern American jet travel. Pan American Airways became the first commercial carrier to take delivery of the elongated, swept-wing planes, launching daily flights from New York to Paris. The 707 quickly became a symbol of postwar modernity—a time when air travel would become commonplace, people dressed up to fly and flight attendants reflected the epitome of chic. The plane even inspired Frank Sinatra’s hit song “Come Fly With Me.”

March 27, 1977: Disaster at Tenerife

In the greatest aviation disaster in history, 583 people were killed and dozens more injured when two Boeing 747 jets—Pan Am 1736 and KLM 4805—collided on the Los Rodeos Airport runway in Spain’s Canary Islands. The collision occurred when the KLM jet, trying to navigate a runway shrouded in fog, initiated its takeoff run while the Pan Am jetliner was still on the runway. All aboard the KLM flight and most on the Pan Am flight were killed. Tragically, neither plane was scheduled to fly from that airport on that day, but a small bomb set off at a nearby airport caused them both to be diverted to Los Rodeos.

1978: Flight goes electronic

The U.S. Air Force developed and debuted the first fly-by-wire operating system for its F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter plane. The system, which replaced the aircraft’s manual flight control system with an electronic one, ushered in aviation’s “Information Age,” one in which navigation, communications and hundreds of other operating systems are automated with computers. This advance has led to developments like unmanned aerial vehicles and drones, more nimble missiles and the proliferation of stealth aircraft.

1986: Around the world, without landing

American pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck) completed the first around-the-world flight without refueling or landing. Their “Rutan Model 76 Voyager,” a single-wing, twin-engine craft designed by Rutan’s brother, was built with 17 fuel tanks to accommodate long-distance flight.

Source https://www.wanderarti.com/the-concept-of-travel-in-art-through-the-ages/

Source https://culturetourist.com/cultural-tourism/history-of-travelling-how-people-started-to-travel/

Source https://www.history.com/news/history-flight-aviation-timeline